Investigating Mafia States and Kleptocracies: A Q&A with OCCRP’s Drew Sullivan

Read this article in

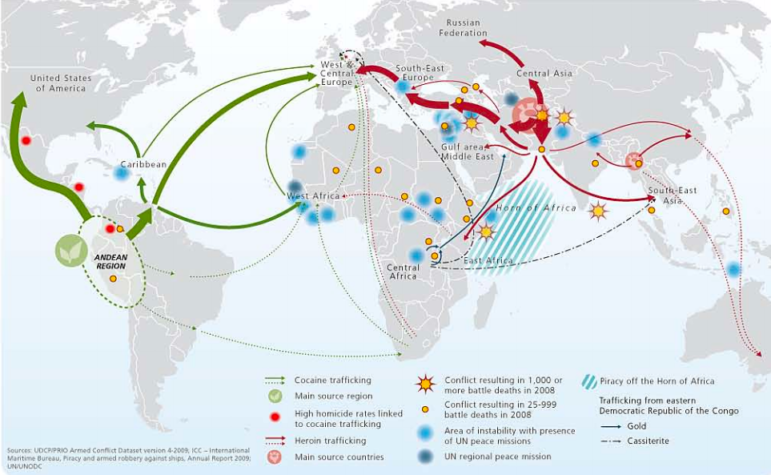

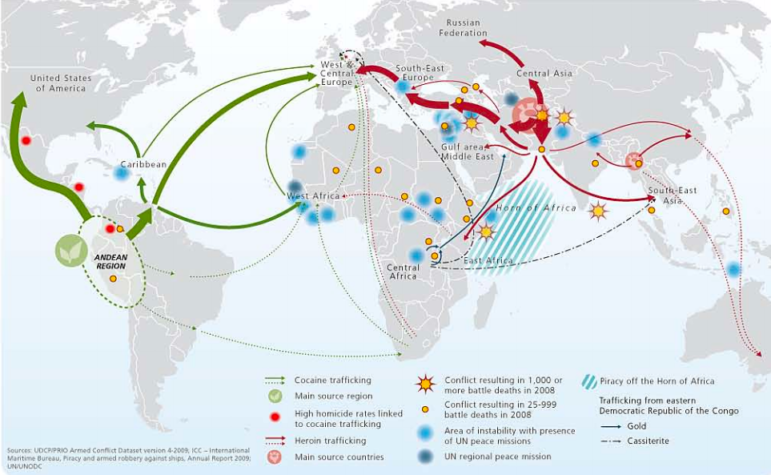

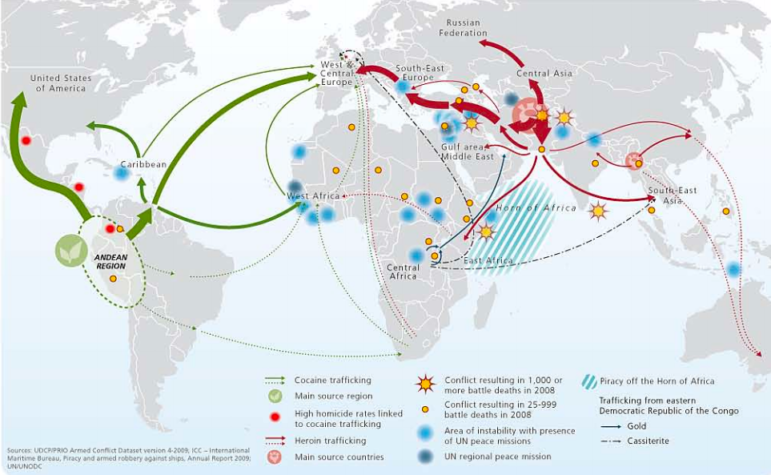

Criminal networks charted by the UN Office of Drugs and Crime. What happens when entire states are part of the problem? Image: UNODC

Editor’s Note: GIJN is at work compiling a global guide for journalists to investigate organized crime. Written by some of the world’s top crime reporters, the handbook consists of 10 chapters, each one covering a different topic such as criminal finance, narcotics, antiquities trafficking, human trafficking, cybercrime, and environmental crime. We’ve already released chapters on criminal finance, by Paul Radu of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), and on human trafficking, by two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Martha Mendoza. More chapters are on the way, with the full manual to be released at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference this Nov. 1-5.

Among the chapters is one on what we call mafia states – countries that essentially operate as a criminal cartel and run the affairs of state much as a crime syndicate runs rackets. To explore this topic, we asked GIJN’s executive director David E. Kaplan to interview Radu’s co-founder at OCCRP, veteran editor and reporter Drew Sullivan. Kaplan has written on crime and corruption for over 30 years and is author of three books on international crime, including “Yakuza,” widely considered the definitive work on the Japanese mafia. Sullivan is publisher of OCCRP, which under his leadership has done ground-breaking work exposing organized crime in former Communist countries and around the world. Since OCCRP’s launch in 2005, its stories have helped lead to $7.3 billion in fines levied and monies seized; over 100 resignations and firings; and hundreds of arrests and indictments.

The interview with Sullivan went long – it turned out both journalists had a lot to say on the subject. So we are running here a lengthier version than what will appear in the crime guide. The conversation veers from mafia states and kleptocracies to corporate crime, and ends with a look at the tools we journalists need to investigate what may be the gravest threat to democracy today. Let us know what you think.

David Kaplan: Since 2012, OCCRP has named a “Person of the Year” – an award basically for using organized crime and corruption as a governing style. If you count up all the countries ruled by the winners, that’s nearly 10% of humanity. And those are just the ones you’ve selected so far. How prevalent is this as a form of governance? There are 195 countries in the world, how many of them can we call mafia states?

Drew Sullivan: Mafia states themselves are fairly rare. If you refer to kleptocracies, those are very common.

DK: Kleptocracies — government by theft, in other words.

DS: Yes, that’s quite common. There are many kleptocracies. Unfortunately, it’s a majority of the developing world. Mafia states are less common. There are probably six or seven of those, in the sense that their mission is to basically be a mafia-like organization. Their intent is to operate the state as a criminal enterprise to further criminal interests.

The great mafia states are probably Kosovo, Montenegro… Malta is probably pretty close. You could argue that Russia is a mafia state — although Russia is probably in a class of its own. Also Equatorial Guinea. Perhaps Mexico.

DK: What about Afghanistan? Here’s a country now controlled by a group branded as terrorist, likely to become a major arms dealer, heroin supplier, and all-around rogue state.

DS: I wouldn’t call it a mafia state because the dominant groups are the Taliban, a kind of coalition of theocratic interests; ISIS; and some warlords. The Taliban has been open about its use of opium as a cash crop but that’s more of a pragmatic decision. The trade routes are in place and there’s little else of interest to international markets, so it will get sold. Their motive is not to be drug dealers, but such profits will always be a problem to rule of law.

DK: And Venezuela?

DS: Venezuela is very much a mafia state, because they’re not interested in running the government anymore. The political elite and military spend their energy not improving security or education but in setting up offshores and drug deals.

Azerbaijan is a kleptocracy. It’s a terrible, autocratic government. They repress people, but most of the money being stolen is to control other people, so that they cannot create a risk to the governing family. They steal everything, not because they need more money. They just don’t want anybody else to have enough money to go against them.

DK: That’s a hell of a distinction… When you see US law enforcement go after organized crime, they build a case under anti-racketeering law that indicts the group as a “continuing criminal enterprise.” But if we really applied that definition, we could indict much of the world.

DS: Yes, absolutely.

DK: So that’s one parameter, right? We live in a corrupt world where there are trillions of dollars annually that are illicitly changing hands.

DS: Exactly. And a big trend that you’re seeing now is that people are legalizing corruption. That’s why we voted the Romanian parliament as OCCRP’s Person of the Year, because they essentially wanted to say it’s okay to be a criminal. As long as you become a parliamentarian, you can’t be charged with anything. And this is true in places like Russia, where members of the Duma can’t be charged with any crimes. That’s a very bad sign.

DK: So we’re talking about a relative handful of countries that are out-and-out mafia states — they’re thuggish, they’re criminal enterprises, they’re based on rackets. These guys have their fingers in everything, backed by violence — the attributes we think of as a mafia. Okay, that’s on one end. And on the other end are these kleptocracies where it’s government by theft, and this includes almost everybody else but Scandinavia and Singapore?

DS: It’s everywhere that’s not a strong democracy. Take Indonesia — the military controls most of the industry, they change the laws, they avoid prosecution. Is it a kleptocracy? Yes, partially, but it’s still partially a democracy. So you have these countries in the middle. But many others are just pure kleptocracies — most of Africa is autocracies, for example. Votes are manipulated, people are paid off. It’s very much a patronage system.

DK: We want to give journalists an analytical framework for looking at their own country. Do they live in a continuing criminal enterprise? Or is this a bit of an overreach, and it’s just handy for a couple dozen countries?

DS: No, it’s not an overreach. It’s a continuum from a transparent democracy to an organized crime state, and states move back and forth along the line all the time. It’s essentially true that most governments are not democratic, and that there’s a tremendous amount of corruption going on. The real problem is when you get state capture. The question is, do you have the power to throw the bums out? If you don’t, then essentially you have state capture, and you’re probably close to autocracy and kleptocracy. Even where you have democratic countries — places like Poland and the Czech Republic – those are backsliding badly.

DK: But that’s more of a political issue than a criminal one.

DS: Right. But sometimes people act political when they are not. We think of all politicians as motivated to be great leaders but what if their real goal is state capture or to be criminal? What if their goal is to use democracy to capture the state? That’s the goal of many politicians, including the Republican Party in the US, and yet we allow this illusion to continue and treat them with respect. I wouldn’t send the State Department to negotiate with Putin. I’d send the FBI.

DK: This analysis of using anti-racketeering law to analyze governance also applies to major corporations, I think. There are major companies out there that would also fit this definition of a continuing criminal enterprise. I think of certain tobacco companies, some firms in the pharmaceutical industry. How would you apply this to major multinationals?

DS: Especially some companies that operate in countries that are autocratic. You’ll see a lot of Turkish companies in the construction industry, for example, or companies in the natural resource exploitation business. They simply go into a country, and bribe and manipulate to get what they want. You cannot go into Equatorial Guinea and deal with the ruling family without paying bribes. As you get more and more kleptocratic governments, the people who succeed are the most corrupt businesspeople.

DK: That’s a good description of what’s going on with companies engaged in payoffs to grab market share and resources. But I think there’s another category of, say, the pharmaceutical industry, in the way that it fostered the opiate epidemic in the United States. Essentially, they were acting as narcotics pushers.

DS: Legal drug dealers, yeah.

DK: The tobacco industry has abetted smugglers, again to create market share. These are billion-dollar black markets they’re fostering — with all the attendant corrupt practices that go with that.

DS: Yeah, the tobacco industry does all sorts of things. The industry is a lucrative funding source, whether it’s a corrupt government or an organized crime gang. It costs 20 to 50 cents to make a pack, and everything between that and the sale price is either tax revenue in the case of legal cigarettes, or profit to criminals in the case of smuggled cigarettes. So, yes, these are criminal enterprises.

You can have ongoing criminal conspiracies by many types of businesses, because once you go into the world market, there’s no global law. There are just weak agreements, protocols, and treaties between countries. Law enforcement is a national boundary entity. Individual laws of individual countries apply, but you can always move things across borders and out of reach, which is what the offshore industry has done for years. The criminal services set up by the offshore industry has made all this extremely lucrative. You can pressure the BVI to expose who is behind something, but you can’t pressure Russia, or China, or Turkey. Consequently, it’s become easy to avoid any kind of enforcement.

DK: Are there certain industries that are more prone to criminal enterprise? For example, I wouldn’t think of the healthcare industry or education so much, but I would with resources, banking, or shipping.

DS: It tends to be around assets, because a lot of these autocratic countries don’t have functioning economies, all they have is natural resources. [US Senator] John McCain famously said Russia is a big gas station masquerading as a country, and there is a lot of truth to that. So, it’s exploitation of natural resources: timber, oil and gas, minerals. And then the vehicles to move these resources around, like shipping, because they’ve got to hide them.

DK: For an investigative reporter prospecting for stories — if you’re looking for that sweet spot of truly egregious corruption and racketeering — where does the nation-state meet these industries? Is it in resources, or transportation?

DS: Follow the money. It’s basically things that are of value in and of themselves, so when you dig it up from the ground, or when you cut down the tree, it has value. Any kind of natural resource is an industry you want to look at, because that’s the only thing that these autocrats — or the mafia states — can make money off of.

DK: More in goods than in services?

DS: Yes. The one service area where you do make money is money laundering.

DK: But that’s in service of the goods, right?

DS: But it becomes an industry in itself. So places like Dubai have grown up to become money laundering centers, and to deal with things like gold and diamonds, and launder those and hide the assets. And now Azerbaijan, the White City that they’re building is designed to be another Dubai. Everybody wants to create their own Dubai, the kind of place that international law enforcement can’t get information out of. That sector has become a criminal enterprise in itself.

DK: Is London’s financial industry a criminal enterprise?

DS: Yes, part of it. Offshore money may be the majority of the money that greases the city and much of that is criminal. That’s why so many Russian oligarchs rejoiced at Brexit.

DK: What about traditional money laundering hotspots, like Panama or the BVI?

DS: Most of these offshore locations are not really criminal enterprises. They’re just making a lot of money off of the trade.

DK: What about the United States? The US doesn’t aggressively prosecute money laundering.

DS: Right. It’s the legalization of corruption. They’ve legalized aspects of corruption because people make money off of it. Hedge funds may be the largest vehicle on Earth for investing criminal proceeds.

DK: Can you give some examples of countries you would call mafia states?

DS: Montenegro is a good example. It’s a small country — only 600,000 people – and was run by someone whose first job in life was Prime Minister. He had close ties through his brother to organized crime, so they started in the illegal tobacco trade, and the state was actually participating in the trade. We discovered over time the mechanisms that he set up to further this. The Prime Minister privatized a bank to his family and started pouring huge amounts of government money into it, and created rules that other people, if they were going to do a deal, had to work through this bank. Then he started loaning the money from the bank to himself, his friends, and organized crime. When it failed, he bailed it out with taxpayer money.

DK: What’s another mafia state case study?

DS: Kosovo is a clear example. The leadership is actually the old Pec mafia. Serbia actively works with criminal gangs who fund the governing party. Malta really looks like it works on behalf of criminal groups. And Equatorial Guinea — Teodoro and his group, the Obiangs — that’s been a major transshipment point for drugs.

DK: What about Duterte’s Philippines, where the state has used extrajudicial killings in a systematic way?

DS: It’s corruption, and it’s a violation of human rights, but Duterte has fairly small connections to criminal activity. He’s been enriching himself and the people around him, but it’s still more political than truly criminal from what we know now.

DK: The most obvious example I know is North Korea, which I wrote about 20 years ago. I remember when I was reporting it, someone explained that usually when we see a mafia take over a government, it comes from the bottom up. This was entirely top down.

DS: Right. But there’s a reason for that. It’s access to international currency. Their big problem is that they need foreign exchange. But they sell nothing, and they’re international pariahs. So, they’re counterfeiting US dollars and selling drugs.

DK: Their diplomatic posts didn’t have enough money. They were selling counterfeit CDs and smuggling tobacco to make their budget.

DS: That was true in Eastern Europe. During the Cold War, most of these countries exported their organized crime figures. That’s why all these Serbians were in Sweden and other places, basically to earn money. The state of Romania was trafficking in drugs to earn foreign currency. That was a popular approach. And that’s the environment where Putin grew up, when he was in the FSB. They figured, “Oh, we have to do it for the good of the state.” But it created this attitude that states can coexist with criminal enterprise, because it’s in their interest. And that’s been passed on.

DK: Well, to a certain extent, if you’re in the intelligence business and you need to get things done, you need to be aware of what the underground markets are. When people were smuggled out of China after Tiananmen Square, the CIA used Triad connections to spirit them out of the mainland.

DS: Putin uses them, too — he arrested a lot of the major organized crime figures in Russia. And then he released them. We suspect the agreement was “You now work for me.” The murder squads sometimes are organized crime people, who go out on behalf of Russia.

DK: Let’s move to tips and tools here. Is investigating a mafia state qualitatively different than, say, investigating a crime cartel?

DS: It’s easier in many ways. Because you still have state records, documents, tenders, companies, you have information.

DK: You have to run a state, and some of that’s going to be public.

DS: Exactly. A state is a more transparent entity than an organized crime gang. You piece together the hierarchy of the organization starting at the top, as you would with a crime gang. There are informal networks within government that are more important than formal networks often. So, you figure out the people who are most important. You look at who’s getting wealthy, who’s got the nicest house, who’s living close to the President in the fancy new suburb that they’ve created.

DK: How are you doing this? Are you using networking analysis software? You scribble it out on a big whiteboard? You have a bulletin board with people’s photos, like in the old TV cop shows?

DS: All of the above. This is a beat, and you have to patiently suck up all the information you can find. We use a knowledge management system to connect all the data, and it interfaces with other software. Then you follow the money.

Money in an organized crime gang will be from an illegal trade like drugs. In a government, it’s going to be state contracts. Who gets the right to drill oil? Who gets the right to cut down trees? Who owns the phone company? This tells you who are the favorite people in a mafia state. But then, the key is the next step: to define the assets.

DK: Right. Assets play a big role here.

DS: Exactly, because you don’t always know what happens in those manipulations of the money. But you can figure out where it ends up, and sometimes when an asset was bought, where it was bought, how it was bought, and then you might be able to connect it to where in the process of government contracts they got the money.

Each individual is going to have a small group of people around them that may front the assets. You have to figure out who the straw parties are, who their lawyers are, who their family members are, and then look for assets under those names. It’s gotta be someone they trust.

DK: What kind of records are you using? Corporate registries?

DS: Corporate registries, land records, property records. France just made its property records available online — we’re finding all sorts of interesting names in there. There’s a lot of leaked banking data out there which will give you indications of who’s got money and where it is. You need to connect to ICIJ, to OCCRP, to other organizations that have built databases of leaked data. Even if it’s 10 or 15 years old, it’s valuable. A new proxy may suddenly show up in a bunch of old databases.

DK: One of the few developments that has helped our people in the field is that we’re in this era of mass leaks — where you can get an entire company’s records on a thumb drive. How important is that for these kinds of investigations? Have you guys come to depend on that?

DS: It’s gotten to the point where there have been enough of these leaks that the data has become a significant part of reporting. A lot of our time is spent connecting various leaks together to follow the money.

DK: When you start a project, do you spend weeks on source development in the hope that someone’s going to give you a document dump?

DS: Yes, we do that. But at the same time, we’re constantly looking at collecting information, and stuff comes out in ways that are not necessarily leaked — from hacks, ransomware, or scrapes. We’re scraping hundreds of datasets on a regular basis. People find a lot of valuable information with the ransomware industry. Because a lot of companies don’t pay the ransom, their information gets leaked.

DK: What are the ethics of using material that was gained illegally?

DS: It’s questionable, but we’re not soliciting this kind of stuff. We’re not asking anybody to give it to us. We’re taking material that has been made publicly available. And we only use it if there’s an overriding public interest.

DK: These investigations aren’t solely dependent on mass leaks, though.

DS: No.

DK: How much of the work is doing a thorough search of the literature, understanding the patterns, going after the public records, and doing the interviews? In other words, reporting…

DS: The reporting part hasn’t changed at all, we’re still doing the same amount. We’re still doing source development, we’re still requesting public records at a high rate, in fact, more than ever. We’re doing a lot more open-source research. Many of our stories are broken because the girlfriend puts pictures of their trip on the yacht on TikTok.

DK: What about face-to-face source development? How important is that still?

DS: It’s still very important. Investigative reporting hasn’t changed. The problem is a lot of young people don’t know these old skills.

DK: They don’t know how to do face-to-face interviews?

DS: Exactly. They don’t do it — they think they can do everything online. We have reporters who are particularly good on the old shoe leather approach, and others who are particularly good at online stuff, and we combine the two.

DK: What kind of software does OCCRP use to do these complex investigations? We use to call this link analysis – for charting all these relationships, and then adding the money, the assets, and the accounts. How do you make sense of all this digitally? You use something proprietary, or is it off the shelf?

DS: Aleph is one of our big tools, and we designed and built that ourselves. We put all our data into it. Aleph is connected to Linkurious, which we use to build network maps based on the underlying data. It’s got a timeline functionality in it, so you can build a timeline. It’s got cross referencing where you can run databases against each other. You can use tools like i2, but they’re expensive, which is why we generally haven’t used them that much. There’s a bunch of social network analysis tools that are out there, some of them are freeware. But those require somebody who’s got lots of technical skills. Aleph is free, and you can also get access to Linkurious.

DK: What about communications?

DS: We use a Wiki system to share information and collaborate on stories. We use Signal for secure discussion between us. So, it’s fairly simple. There needs to be better tools to do this, but between Signal, a Wiki, and Aleph, we coordinate all of our projects, and all those are available to any reporter.

DK: What about the importance of working in a team? These are big targets. They’re intimidating. Nation states have a lot of resources at their disposal, they can crush an individual reporter. How do you deal with that?

DS: All the big corruption and organized crime stories are cross-border now. So more than ever, it’s critical to have a team with a lot of different expertise. You need local reporters. Cybersecurity reporters. Researchers. Social media experts. Data people who can mine these leaks. We are a network and we use that networking to leverage each other’s skills. That, in fact, is why we are able to do a lot of stories and do them quickly. If you don’t have an organization with those people, you need to build those relationships, using organizations like GIJN.

DK: What if you’re an individual reporter living in a corrupt regime, and you want to start documenting this?

DS: We work with reporters in places like Turkmenistan, very corrupt regimes where they can’t be seen even talking to us. But they can do a lot of work by leveraging connections with reporters in other places. You may not be able to look inside your country, but you can look outside it where the assets are.

DK: Do you think it’s harder for governments today to keep secrets?

DS: It is, because it’s so easy to communicate. Also, because many governments are so corrupt now, a lot of people are disturbed by what’s happening. And that’s where the leaking comes in. I also think it’s a tool that’s being used by governments. I think many of the large leaks have come from governments.

DK: Say a little more about that. You suspect there are intelligence services involved in these mass leaks?

DS: Yes. I think it’s in the interest of certain countries to get this information out. Countries are leaking information that’s in their interest to get out, to hurt other countries, or to hurt people.

DK: How can journalists guard themselves from being used that way?

DS: You have your ethics, and you have to keep a close eye on making sure you do stories that are in the public’s greatest interest. I think that’s the key. We’re constantly arguing this point among ourselves: Does the public really need to know this? We try to make sure that everything we do is explaining corruption, or the way that the government – or business or organized crime — is working, so that the public can make better decisions on what to do.

Additional Resources

A Reporter’s Guide: How to Investigate Organized Crime’s Finances

Human Trafficking: Investigating an Evil Hidden in Plain Sight

Digging into Disappearances: A Guide to Investigating Missing People and Organized Crime

David E. Kaplan is executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network. He has written about organized crime for 35 years and is co-author of Yakuza, widely considered the definitive work on the Japanese mafia. Kaplan has reported from two dozen countries, won or shared over 25 awards, and managed nonprofit newsrooms, investigative teams, and numerous cross-border reporting projects.

David E. Kaplan is executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network. He has written about organized crime for 35 years and is co-author of Yakuza, widely considered the definitive work on the Japanese mafia. Kaplan has reported from two dozen countries, won or shared over 25 awards, and managed nonprofit newsrooms, investigative teams, and numerous cross-border reporting projects.

Drew Sullivan is co-founder and publisher of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Under his direction, OCCRP has won numerous awards, including the Global Shining Light Award, the Tom Renner Award for Crime Reporting, and the European Press Prize. Previously, he worked an investigative reporter for The Tennessean newspaper and the Associated Press’s Special Assignment Team.

Drew Sullivan is co-founder and publisher of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Under his direction, OCCRP has won numerous awards, including the Global Shining Light Award, the Tom Renner Award for Crime Reporting, and the European Press Prize. Previously, he worked an investigative reporter for The Tennessean newspaper and the Associated Press’s Special Assignment Team.