Fotografía de la sala de redacción de El Surtidor, con los cofundadores Alejandro Valdez (de pie en el centro) y Jazmín Acuña (de pie atrás). Imagen: cortesía de El Surtidor

Thriving on Change: El Surtidor’s Groundbreaking Multi-Platform, Visual Journalism

Read this article in

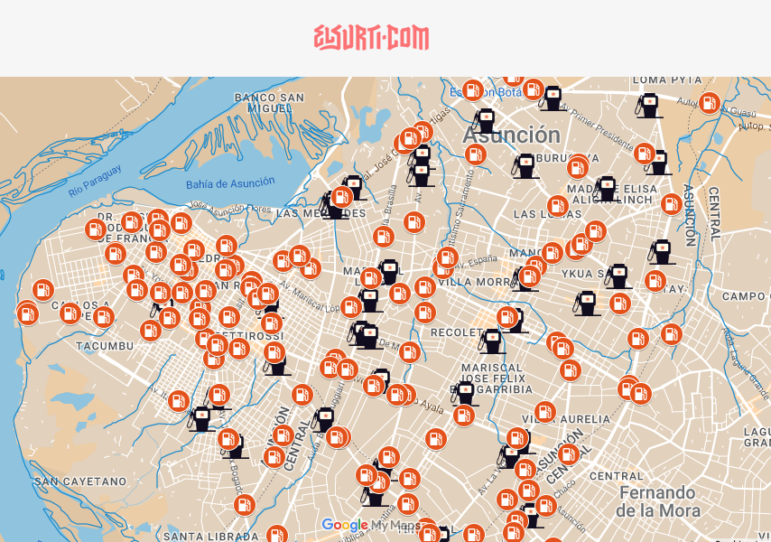

Nearby residents in Asunción, Paraguay, were alarmed when 36 gas service stations were opened between January 2021 and June 2022: approximately two each month. The overwhelming amount of new stations was difficult to ignore. By comparison, the city of Los Angeles, with eight times more people and 12 times the surface area, approves an average of two new gas stations a year.

Studies have shown that living near a service station isn’t safe. Risks include ground-level ozone emissions caused by gasoline fumes and groundwater hazards from petroleum product leaks. Concerned citizens complained to the authorities and the media, but only one platform followed through on their concerns — with an in-depth investigation.

Award-winning El Surtidor (usually called El Surti for short), is a groundbreaking multi-platform news organization created in 2015 that prioritizes innovation. A fresh visual style, creative investigation approaches, appealing audience engagement activities, and strong sustainability solutions have made El Surti one of the more innovative examples of 21st-century investigative journalism. In 2021, it was accepted as a member of GIJN.

Since its inception, El Surti was meant to appeal to a young audience. “We covered topics that we didn’t believe were in the [media’s] agenda, but we also realized it would be very difficult to compete with a young audience that was, at least back then, mostly on Facebook, and later on other social media platforms,” says Jazmín Acuña, co-founder and editorial director. “Therefore, we decided upon doing what we call ‘visual journalism,’ which combines original reporting with images inspired by comics, movies, series, and memes.”

Most of the organization’s founding members have a background in graphic and industrial design instead of journalism, which enables more visually oriented storytelling and introduces a different project management approach.

“Being outsiders helped us break some paradigms without even noticing it,” says Alejandro Valdez, co-founder and director of Memetic.Media, the umbrella organization that brings together El Surti and its fact-checking project La Precisa with the Asunción-based cultural project Fotociclo, the visual journalism workshop Latinográficas, the journalism collaboration project el Laboratorio, and Fábrica Memética, a sustainability project aimed at raising social awareness campaigns for NGO clients.

“Our work process is strongly based on the workflows of designers. All design is forward-looking, and specific steps are taken to mitigate uncertainty about our final result,” explains Valdez. “This implies understanding the context. In terms of design, our proposal has to be the one most helpful to the communities we serve and to our users.”

Legacy news organizations had to adapt when their audience shifted from print, radio, and television to internet websites. Now these organizations are struggling with the newest change: young people abandoning websites and increasingly consuming news through social media platforms. While with every major change in the digital environment traditional news organizations may complain about a ‘crisis in journalism,’ El Surti thrives in today’s fast-paced social media-centered landscape.

Planning how to present a story is not something that happens after reporting at El Surti, but a process that begins when a story idea is pitched. “We try to think about how our products may be tailored to the widest number of platforms,” explains Acuña. “If we use Instagram, we know we can include image carousels and have more text than in Twitter, where we only have one image and a short amount of text. Content needs to be adaptable. We don’t start from zero when we think about adapting a story to a social media format.”

Instagram is the social media platform where they feel the most comfortable publishing, Acuña adds, because it allows stories to be displayed in more depth, it is an eminently visual medium, and the tone of discussions in Instagram is more open and receptive than Twitter’s hostile environment. She also noted that Instagram highlights media organizations, while Twitter tends to revolve more around individual journalists.

Taking on the Power Structures

When El Surti received complaints about all the gas stations being built (some residential neighborhoods saw three new stations within a 300-foot radius), Maximiliano Manzoni, one of El Surti’s investigative journalists, was already following the red flags. A business conglomerate owned by one of Paraguay’s former presidents, who was also the leader of the majority Colorado Party, had recently pushed for scrapping gas station environmental regulations. Those rules protected the Patiño aquifer under Asunción and limited how many stations could be built in proximity to schools or hospitals.

Paraguay’s Supreme Court — which had half of its justices appointed by the same former president — struck down those regulations as unconstitutional, ruling that they violated the right to free enterprise. The door was then opened for a deluge of new service stations in Asunción.

Although El Surti wasn’t the first to reveal the change in regulations or the Supreme Court’s decision, it did analyze the direct impact the ruling had on Asunción. When the city’s government, which was led by an ally of the former president, did not provide El Surti with information on which companies were building new service stations, the investigative team had to design its own methodology. The team cross-checked cadastral geographic information with environmental permits issued by the Ministry of Environment. And in an otherwise useless response to their FOI request, the team found patterns from the list of municipal registry numbers given by the Asunción municipality.

“We used a registry map to pinpoint the location of each gas station,” Manzoni explains. “We went to every place we identified and took pictures with drones, to verify a gas station was being built there. Our last step was to determine if they had benefited from the regulation change. We did this by determining how far each new station was from schools, hospitals, and other gas stations.” he adds. Armed with this information, El Surti researchers and their audience used Google Pinpoint to create an open source map of where exactly each new gas station was located, as well as which nearby schools and hospitals were now in danger.

After the piece was published, El Surti organized meetings with audience members that were affected by the gas stations, such as activists, urban developers, and local government officials, to explain the journalists’ findings. “A town hall meeting sprung up then and there, and an action group was created to protest against the construction of new gas stations,” Acuña says. “A person from the audience told us: ‘You gave us the information. Now we have to act.’”

Using open source information like business records and environmental permits, El Surtidor mapped the rapid rise of new gas stations in Asunción — and their proximity to schools and hospitals. Image: Screenshot, El Surtidor

First and Foremost: the Audience

El Surti’s team holds regular meetings with audience members to receive input about current research topics, share recent findings, and discuss issues that the team may investigate in the future. Adriana Rolón is a cultural manager and agricultural engineering student that regularly attends meetings that El Surti calls “mingas,” a Quechua Indigenous word that refers to assemblies in which people carry out communally beneficial work. As a theater enthusiast, Rolón’s first minga with El Surti involved a group of about 20 people that included journalists, prominent local actresses and directors, and audience members, who discussed Paraguay’s theater history milestones with a focus on women in theater. “As an audience member, I not only come to these meetings to listen, but to work and collaborate,” says Rolón.

Before each minga, El Surti sends an email with an introduction to the topic and a set of questions that will be addressed, and, once assistance is confirmed, audience members receive a training packet through Google Meet. Each attendee is expected to prepare for the discussions that will take place.

Rolón says this relationship between El Surti’s journalists and its audience strengthens trust in their reporting: “This a totally different approach from traditional media, which throws a headline at you and you’re supposed to believe it. With the kind of activities El Surti conducts, we participate in an investigation process. We’re not just listened to, but actually working and contributing.”

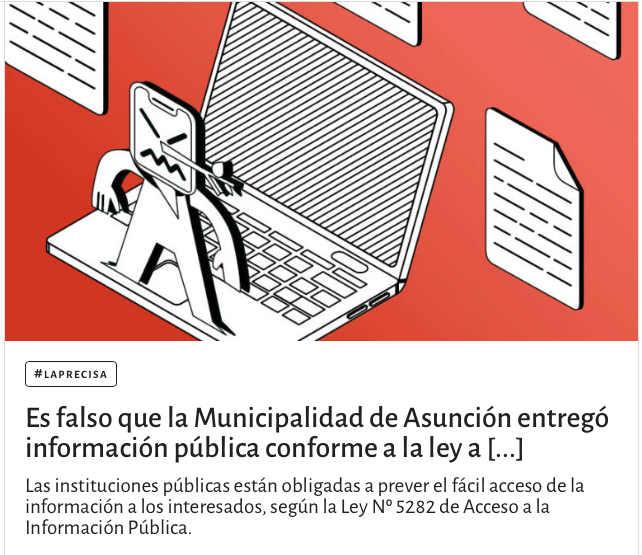

The community-building ethos that drives El Surti is also present in its fact-checking and disinformation studies project, La Precisa. Josue Congo, who leads this project, describes La Precisa as being more than a traditional fact-checking website. Beyond determining if a politician’s statements are true or false, or if a photograph is fake or legitimate, La Precisa aims to answer why and how disinformation arises, and relies heavily on a network that includes audience members and small regional media around Paraguay. Together the team identifies as many disinformation sources and products as possible and feeds a database from which studies are conducted. La Precisa is also a member of Latam Chequea, a network that brings together media outlets with fact-checking sections from Latin America, the US, Spain, and Portugal.

El Surtidor’s La Precisa team not only fact-checks claims, it digs into the roots of disinformation by tapping into the site’s audiences and networks in the Paraguayan community. Image: Screenshot, El Surtidor

Innovative Sustainability

Alejandro Valdez says El Surti’s annual budget is slightly more than US$200,000 dollars. About 90% of the site’s expenses are the salaries for the 12-member team, while the remaining 10% covers operational costs and technology tools. Its main income sources are international cooperation grants, impact investments, audience donations, sales from their online store and magazines, and more recently, Fábrica Memetica (Memetic Factory), El Surti’s flagship sustainability project, that currently generates more than 20% of their income and is steadily growing.

The Fábrica Memética project was initially meant to solve the immense sustainability challenge most independent web-based media face when they try to reduce their reliance on international cooperation or grants. El Surti also has to deal with an additional difficulty: Paraguay’s market is too small to make sustainability through audience subscriptions viable.

At its core, Fábrica Memética offers communication campaign services, mainly to NGOs or international cooperation agencies. However, according to Carol Thiede, the project’s director, who used to work in communications with Oxfam, Fábrica Memética has merged El Surti’s journalistic style with awareness-raising campaigns tailored for clients such as UNICEF, the International Labor Organization, Amnesty International, and the World Bank. These campaigns include illustrations, photos, video, and multimedia design for social media.

Initially, El Surti planned for its sustainability project to center on publishing and editing projects, “but soon we were mostly doing digital campaigns, which I was familiar with from my work in Oxfam,” says Thiede. “Our clients were mostly from international cooperation because of the networks we had built. El Surti also gave them added value because we know about the topics they need us to campaign about and we already use elements they want to see in their communications products, such as inclusive language.”

El Surti was born eight years ago amid two large student protests in which many of the founders took part: one by university students frustrated with corruption, and another by high school students angered by the poor conditions of their school buildings. Collective action and accountability are part of the founders’ DNA, and they belong to a generation that has always used social media as a political tool. Strong visual communication, meaningful messaging, and social commitment through a wide range of projects and platforms make El Surti a media outlet that places public service at its core, while it faces future media changes with a refreshing dose of optimism.

Additional Resources

Peru’s Investigative Journalists Carry On Amidst Disinformation, Attacks, and Political Crisis

How Mission-Driven News Sites Are Betting on Reader Revenue in Latin America

How They Did It: Covering One of the World’s Most Dangerous Border Crossings

Santiago Villa is an award-winning journalist who has written for Latin American news outlets for more than a decade. He is currently based in Colombia, and writes an opinion column for El Espectador. He has previously worked as a foreign correspondent in South Africa, China, Venezuela, and Ecuador.

Santiago Villa is an award-winning journalist who has written for Latin American news outlets for more than a decade. He is currently based in Colombia, and writes an opinion column for El Espectador. He has previously worked as a foreign correspondent in South Africa, China, Venezuela, and Ecuador.