Image: Shutterstock

Guide to Investigating Digital Ad Libraries

Read this article in

Digital advertising is a half-trillion dollar a year industry and a core element of global marketing and election campaigns. Digital ads are also commonly used in influence operations, scams, and cybercrime.

Yet, in my experience, ads are rarely mentioned or taught in OSINT and digital investigative courses. I believe they’re one of the least investigated and most poorly understood aspects of the digital economy. I’ve been trying to change that by giving ad investigation workshops and by drawing attention to tools and techniques in this newsletter. I previously listed free digital ad tools and described a reporting methodology I used while investigating Google’s ad business.

Now I want to introduce you to the easiest way to get started with digital ads: ad libraries. Every digital investigator should know how to dig through digital ad libraries.

Ad Library 101

The landing page of Meta’s ad library. Image: Courtesy of Silverman

- When an ad ran

- What they looked like/said

- Which platform it ran on

- Who the advertiser was, and what other ads they’ve run

- Which country(s) it was shown in

In some circumstances you may see:

- The destination URL of the ad

- The name of the person or entity that paid for the ad

- Contact information for the person or entity that paid for the ad

- Roughly how much was spent

- Additional targeting data such as geography and age group

List of Ad Libraries

- AliExpress (EU, UK)

- Amazon (EU/EEA)

- Alphabet (Global, with exceptions)

- Apple App Store (“select European countries”)

- Bing (EU/EEA)

- Booking.com (EU/EEA)

- LinkedIn (Global, with exceptions)

- Meta (Global, with exceptions)

- Pinterest (EU)

- Snapchat (EU)

- TikTok (Global, with exceptions including the US)

- Zalando (EU/EEA, UK)

- Twitter/X (EU)

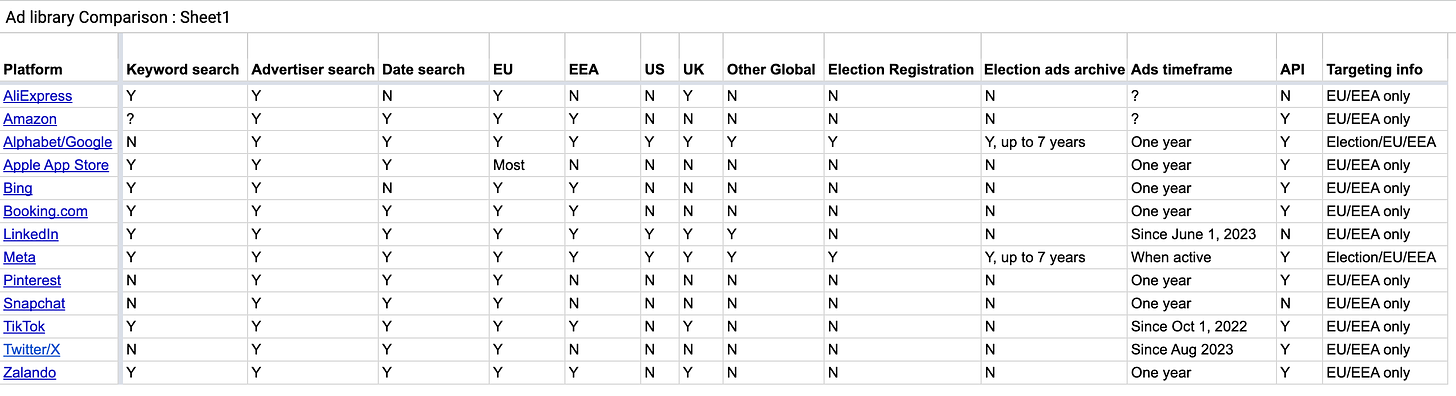

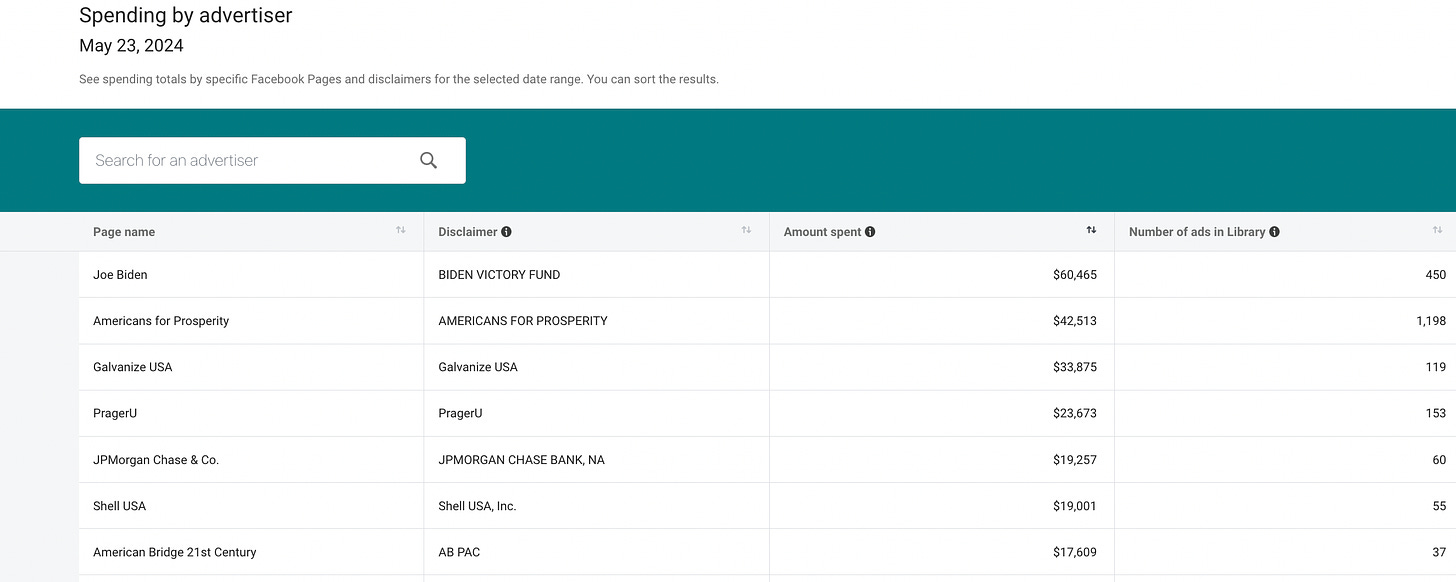

Comparing Ad Libraries

Mozilla report ‘Full Disclosure: Stress testing tech platforms’ ad repositories’: Image: Screenshot, Mozilla

none is a fully-functional ad repository and none will provide researchers and civil society groups with the tools and data they need to effectively monitor the impact of VLOs advertisements on Europe’s upcoming elections.

The situation is worse for non-EU/EEA countries. Only Meta, Google, and LinkedIn offer access to ads that have run in a wide range of countries. It’s difficult to keep track of the differences between libraries, so I maintain a chart (see below) that breaks down some of the key features. (I do my best to keep it up to date.)

A few things to highlight:

- Most ad libraries allow you to search for ads by geography, date, and the name of the advertiser or account that placed the ad.

- Some libraries let you filter by the ad format (video, text, etc.) or by the ad category (election/issues, employment, etc).

- Several libraries do not allow keyword searches, including Google’s. Yes, the ad library from Google is not searchable by keyword. Hopefully this feature is in development…

- Ads that were shown in EU countries may offer additional targeting information.

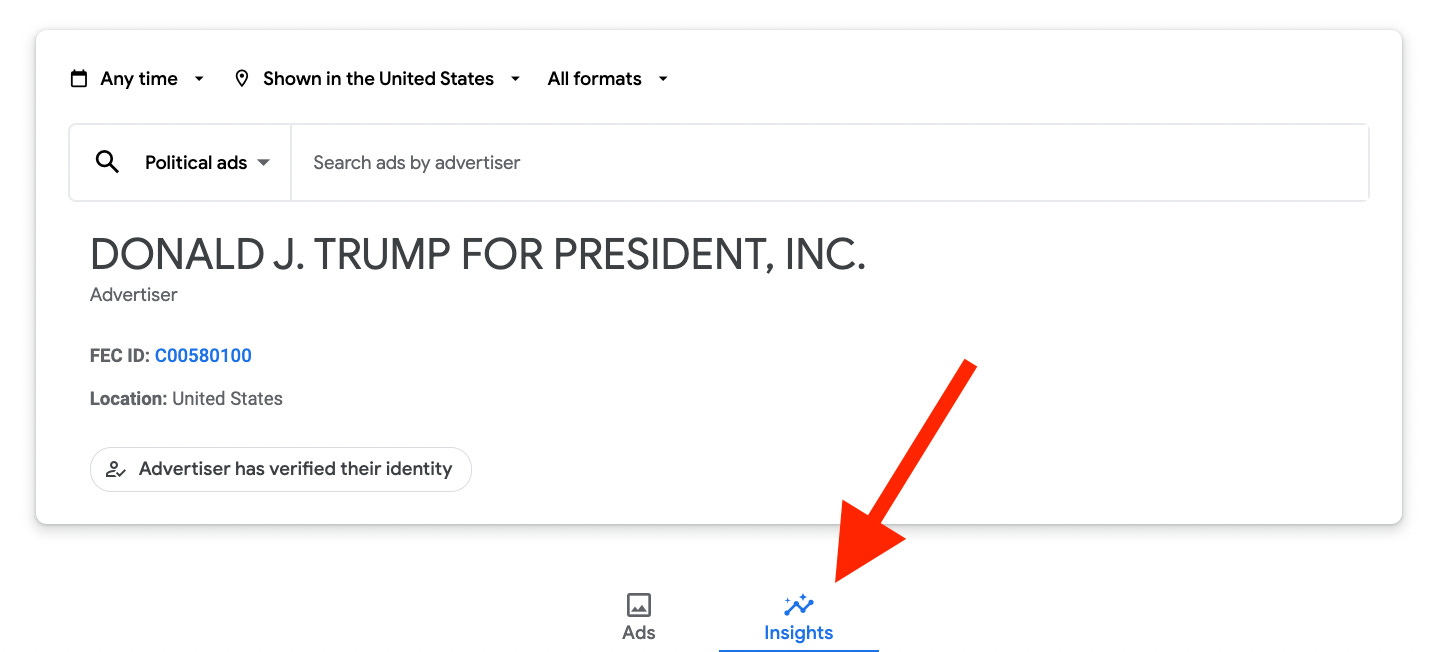

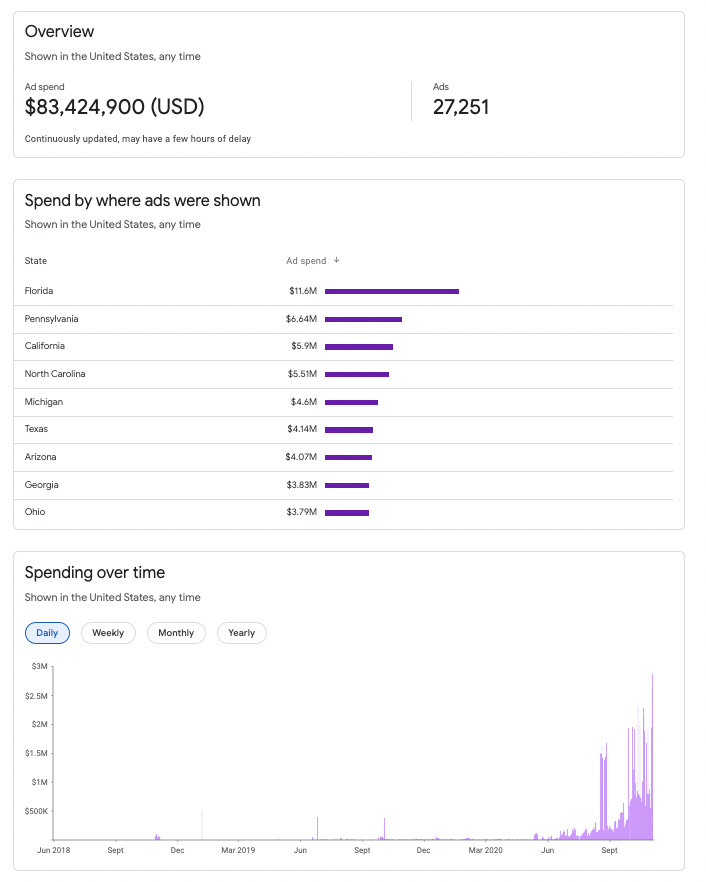

- Some platforms, such as Meta and Google, require advertisers to go through a special registration process if they want to run political/social issue ads. Such ads are archived for a longer period of time (often seven years), show additional targeting information, and disclose info about who paid for the ad.

- For non-political/issues ads, most libraries let you see ads that have run in the past year. Meta, however, only shows ads that are currently active. So when a campaign stops running, the ads disappear from the library.

- Some platforms, like TikTok, say they do not accept political ads. Others, like Google, only accept them in certain countries.

Lots of differences and inconsistencies! If it seems confusing that’s because it is.

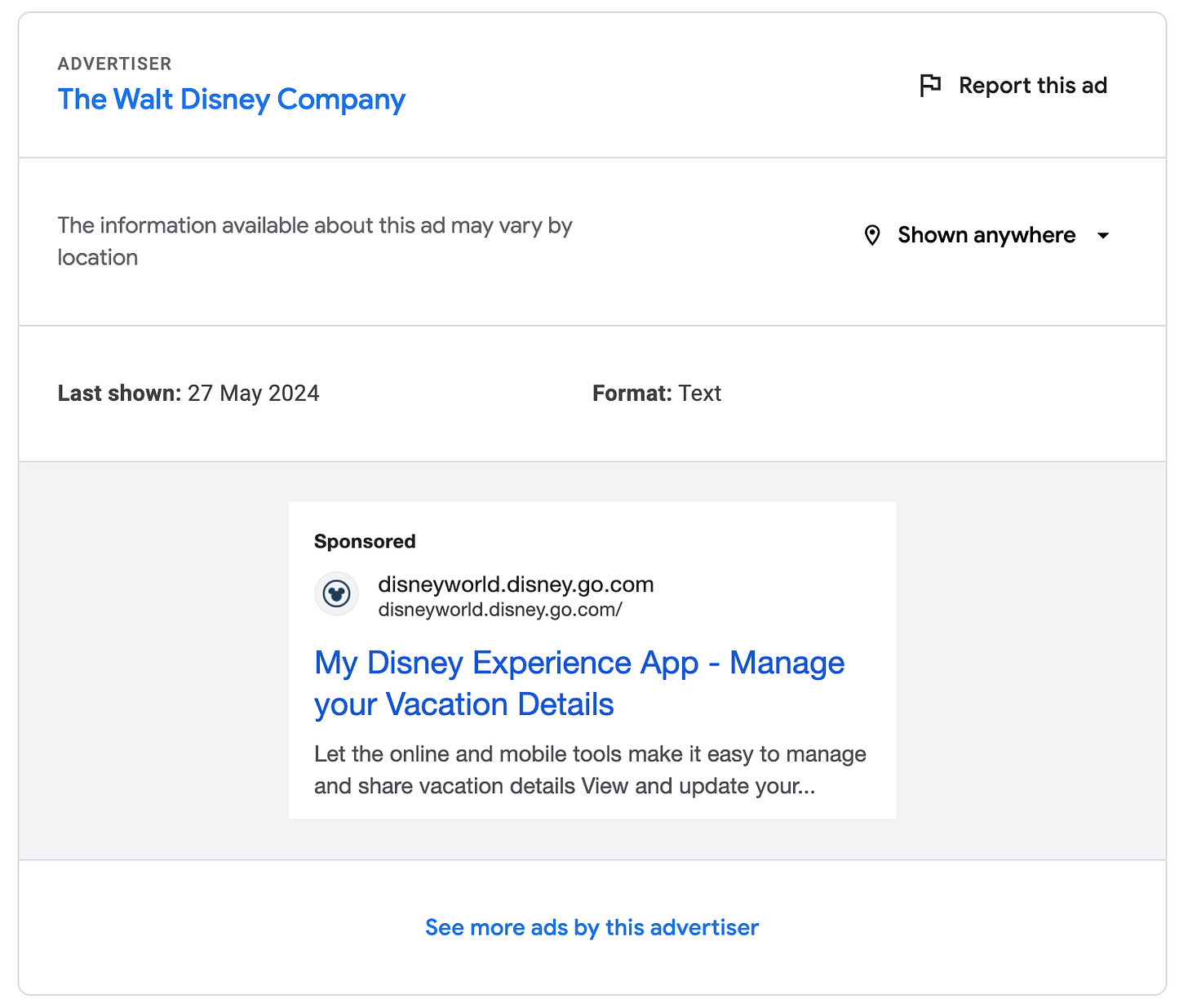

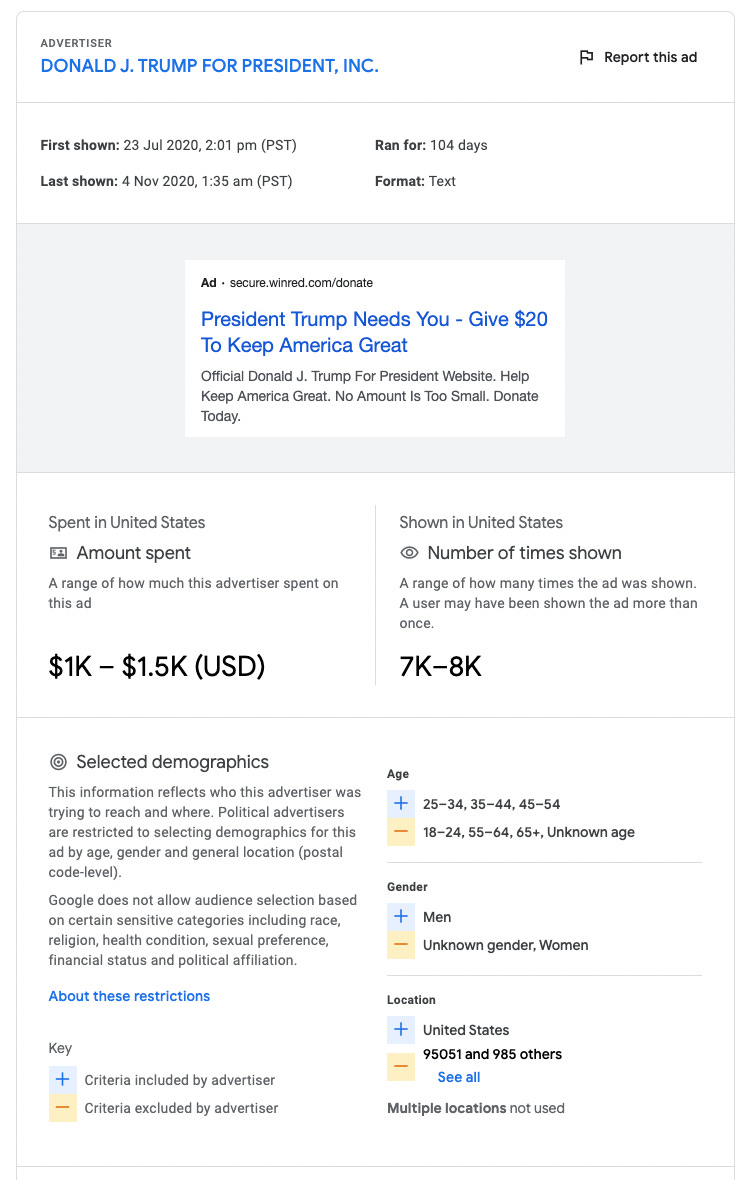

You can see the ad and the entity that ran it. You can also click on the name of the advertiser to see all of its recent ads. Now here’s a political ad from Donald Trump’s 2020 presidential campaign (below):

Integrating Ad Libraries Into Your Workflow

Ad libraries are important if you’re reporting on elections. The workflow is relatively straightforward:

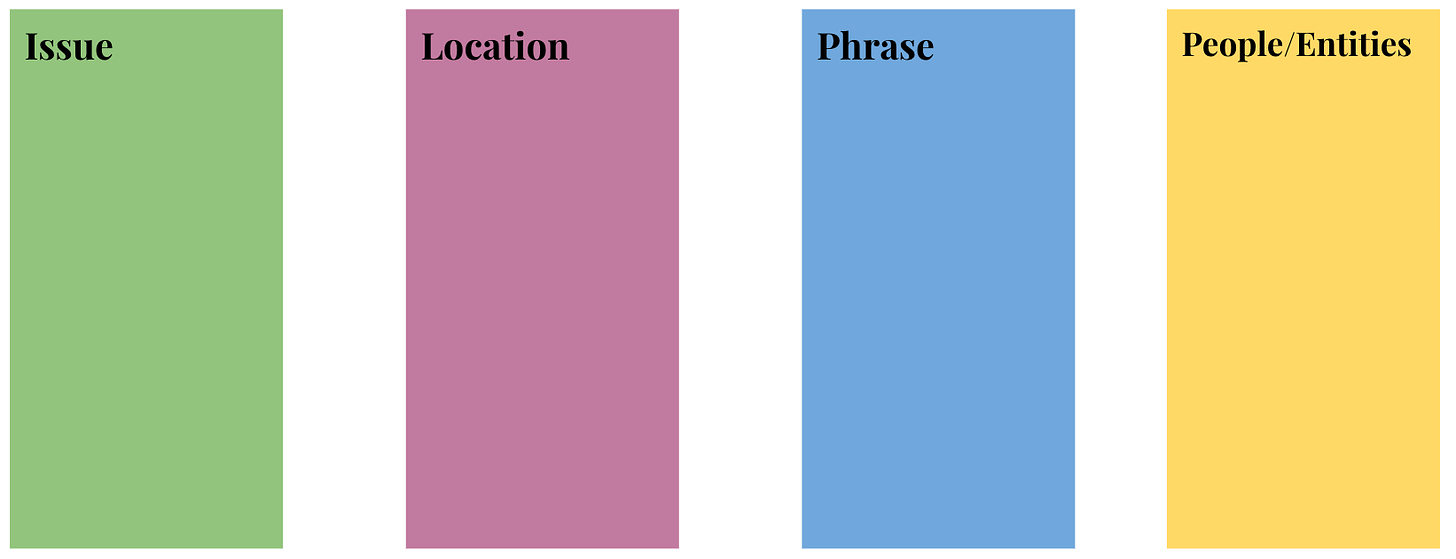

- Identify all of the candidates, parties, issues, etc. of interest. Make a list of keywords, phrases, entities, and accounts.

- Search across ad libraries to find ads and accounts.

- Capture relevant ads and take note of narratives, destination sites, etc.

- Pivot on ad content, accounts, destination websites, and other assets to identify networks and actors of interest.

- Repeat.

This works for any beat or topic. I encourage all reporters and investigators to integrate ad libraries into their workflow. Any person, company, or entity could run ads or be the subject of them. Just as you check to see if a person has registered a company or domains, you should see if they run, or are the subject of, digital ads. The same is true for issues, topics and beats: they may be the focus of interesting or newsworthy ads.

As noted above, a first step is to create a list of keywords to use in ad library searches. I suggest brainstorming keywords in the below categories to kickstart the process of coming up with search strings.

Some libraries don’t offer keyword searches. That’s annoying but ok; you can still generate lists of countries and advertiser/entity names and accounts.

Political/Issues Ads

Final Advice

- Turn off your ad blockers when using ad libraries.

- Test and retest keywords.

- Check frequently because ads disappear.

- Take screenshots.

- Take notes as you go.

- Search, monitor, capture, and adapt!

What did I miss? Have other tips to share? Please add them in the comments. This isn’t my last word on ads: I’ll soon highlight a couple of technical tools for ad investigations.

This article was originally published on Craig Silverman’s Substack newsletter, Digital Investigations, it is reposted here with permission.

Craig Silverman is a national reporter for ProPublica, covering voting, platforms, disinformation, and online manipulation. He was previously media editor of BuzzFeed News, where he pioneered coverage of digital disinformation.

Craig Silverman is a national reporter for ProPublica, covering voting, platforms, disinformation, and online manipulation. He was previously media editor of BuzzFeed News, where he pioneered coverage of digital disinformation.