New Investigative Tools for Monitoring Social Media Platforms

Read this article in

Social media platforms are among the most difficult sites to scrape for data across the internet.

Yet this is a crucial function for data and investigative story leads if you want to, for instance, see who is behind harmful ads on those platforms, or track TikTok’s recommendation algorithm, or identify the conspiracy groups or influencers who are spreading disinformation.

One reason for this problem, experts say, is because some platforms’ security teams deliberately make scraping difficult, in a claimed effort to deter bad actors. But this tactic also stymies investigative journalists seeking to track toxic accounts or suspicious individuals.

So, in recent years, journalists have come to rely on platform-owned insight tools like CrowdTangle to track content from Facebook and Instagram posts, and Twitter’s application programming interface, or API, to dig into tweets. But there are looming problems for journalists with these dashboards, too.

“Their future is cloudy,” warns Jeremy Merrill, data reporter at The Washington Post. “CrowdTangle is an important tool, but it has been reported to be going away. Likewise, Twitter API has historically been super-open. However, Elon Musk has promised to make the API paid-for, and has made conflicting statements about what data will even be available to researchers.” In fact, Twitter rolled out new paid tiers for API access in early March that priced out nearly everyone except large corporations.

Meanwhile, no such content access tool even exists for major platforms like TikTok.

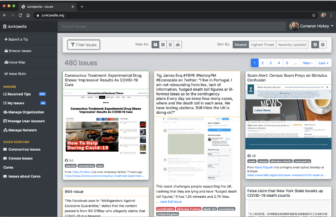

In response, the recent NICAR23 conference — the annual data journalism summit organized by Investigative Reporters & Editors — devoted a major session to an increasingly popular tool that monitors public accounts across numerous platforms for the benefit of journalists and researchers — Junkipedia.

Junkipedia was developed by the Algorithmic Transparency Institute, a project of the US-based National Conference on Citizenship, a Congressionally-chartered nonprofit “dedicated to strengthening civic life in America.” Originally designed to monitor disinformation and “junk news,” Junkipedia has developed to the point where the tool will change its name this year, to reflect its new global, all-purpose digging role.

Junkipedia was designed by, and for, investigative journalists and researchers — and it’s free.

Some caveats: It does not have the most comprehensive datasets, or access to every public Facebook page, as CrowdTangle does — and its user interface has been described by some researchers as “clunky” compared to the big, well-funded social insight tools.

But its advantages are notable. At NICAR, there was a murmur of excitement from the panel audience when veteran journalist Cameron Hickey — CEO of the National Conference on Citizenship — declared that Junkipedia seeks to be “the CrowdTangle for everything!”

In addition to its shared database of problematic social media content, Hickey said Junkipedia now allows users to track and build lists of social media accounts from a dozen different platforms — including fringe sites like GETTR and Gab, as well as major sites like TikTok, Facebook, and Telegram.

Remarkably, Junkipedia can also automatically transcribe and search English-language podcasts.

“We’ve significantly expanded what the tool does — so it is a platform in search of a new name,” said Hickey. “You can build a list of accounts on the platform from any of these 12 social media platforms, and from podcasts, and the system will automatically surface all of the posts from those accounts. For some of those, it can also show you posts from search queries.”

He added: “For example, for Youtube, you can enter the terms ‘ballot’ and ‘fraud,’ and it will search for where those terms appear in the title or description of a video, and show you data about all of those videos. You can also view lots of metadata about accounts.”

Hickey invited investigative journalists and data reporters to apply to use the tool using their institutional email.

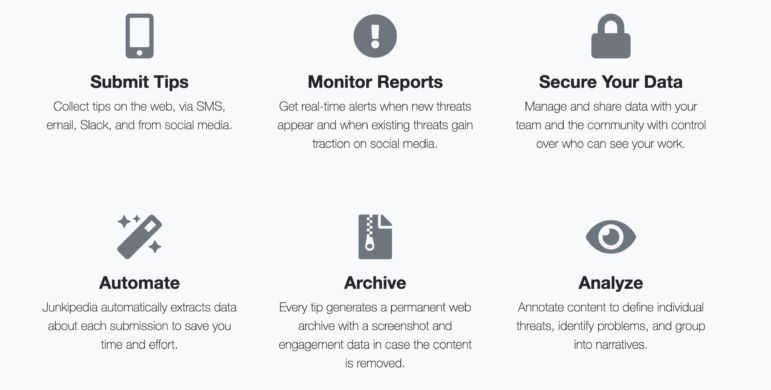

In addition to monitoring 12 social media platforms, Hickey explained that Junkipedia can also:

- Dig into messaging on the same topic on multiple platforms through its new “actor” database. “Actors are usually human beings, but sometimes companies — and often have many social media accounts, so associating all those accounts across different platforms can be very helpful,” said Hickey. Merrill added: “So, kind of with one click, you can see everything that, say, Democratic candidates for office in the state of Georgia have said about marijuana.”

- Show engagement statistics about social media content you’re investigating. “You can look at a breakdown of any engagement metric that social media platforms provide – how many posts there are; the likes and comments and views,” Hickey pointed out. “Notably, since Elon Musk took over, Twitter added views to tweets, which hadn’t been there before, so our system now collects the views from Twitter posts.”

- Expose corporate “greenwashing” and “woke-washing,” by showing politically virtuous social messaging campaigns designed to disguise core polluting or exploitative activities. “Frequently, fossil fuel emitters use social issues to cleanse or elevate their brand in some way – car or energy companies focusing on Black Lives Matter, LGBTQIA+, or the gender identifies of individuals in ads — that researchers view as a form of woke-washing or greenwashing,” said Hickey.

- Be used as a front-end monitoring dashboard, where you can search and filter content.

- Automatically transcribe English-language audio on TikTok, Youtube, Telegram, and podcasts. “Podcasts have absolutely been a black box for years,” said Merrill. “Do you want to listen for hours to Steve Bannon (on a podcast) every day? – No. Because of Junkipedia, we now have those podcasts transcribed.” Hickey added: “You can also extract meaningful topics or identify frequently used terms.”

- Build public social media lists — including lists already built and shared about, say, white supremacists in Australia, or vaccine conspiracists in Europe.

- Create a database of annotated accounts — like accounts for politicians and their respective parties.

- Annotate your live projects via a built-in labeling tool.

Recent Investigative Case Studies

Hickey was joined on a NICAR panel by Merrill and a Wall Street Journal reporter, Andrea Fuller.

Merrill said Junkipedia was a crucial tool in his 2022 investigation “Trump’s ‘big lie’ fueled a new generation of social media influencers,” which showed how social platforms allowed false claims about fraud in the 2020 US presidential election to give influencers an outsized role in promoting other disinformation afterwards. To pursue the investigation, Merrill sought to examine posts and podcasts by 77 influential election fraud claimants after December 7, 2020, when Joe Biden had been clearly established as the winner.

“They used the clout they gained from those lies to talk about other divisive issues, so the permission they were given by these platforms was a reward for them,” Merrill explained. “I wasn’t particularly relishing building a scraper for fringe platforms like Gab or GETTR, or looking at everything right wingers were saying on podcasts. To solve that problem, I turned to Junkipedia.”

For a recent exposé on how misleading marketing boosted metal health companies, Fuller said her team used Junkipedia to help analyze 1,800 social media ads from 15 telehealth firms that ran without risk warnings, or promoted drugs for unapproved uses.

Fuller revealed that some company executives even posed as customers in certain ads, in violation of US drug marketing regulations.

“The Facebook Ad Library has an API, but it’s only for political ads, and we were interested in corporate ads, for a story on telehealth companies, and the ways they distribute controlled substances,” Fuller explained. “Junkipedia gave us all the data from the ads we were collecting, and the links to the images they were hosting, and collected the data for about 30 companies we were interested in. We got about 4,000 ads, and coded them for things like: ‘this ad names a controlled substance; this ad has an actor pretending to be a customer.’”

Junkipedia’s Limits — and Alternatives

Hickey said the tool’s global reach relies on inputs from its users. “It’s been used in a German election, in a recent Australian election — it can be used almost everywhere, but the power lies with the users,” he noted.

However, he also warned that Junkipedia is not a comprehensive tool for all social monitoring.

“There are other tools out there that gather more comprehensive datasets,” Hickey acknowledged. “For instance, CrowdTangle also has some other data that doesn’t come out of their API, so we don’t capture that.”

“In some cases, the questions we’re trying to ask are not ones Junkipedia can answer,” Merrill said.

For social media scraping that Junkipedia cannot do, Merrill suggested that reporters consider:

- Snscrape: a command-line tool that can act like a logged-out user of Twitter to scrape all the content from a particular Twitter page. “It’s open source, so you can modify it if you need to do something fancy,” said Merrill. “As long as Twitter allows logged-out users to see stuff, snscrape is great.”

- SMAT app: which can search and analyze posts in fringe social media sites that Junkipedia doesn’t cover, like 4chan, 8kun, and Parler.

- Waybackpack: a command-line tool that can download the entire Wayback Machine archive for a particular URL. Merrill said an updated feature – “Waybackpack2” – can also find numbers on social media that change retroactively, such as claimed followers on an account suddenly jumping to a much higher number.

Hickey added that journalists with scraping tools should consider how they are using them. Scraping is generally not considered a crime in much of the world, but the ethics of it can be complicated. “Scraping all of Donald Trump’s Truth Social account seems to carry a low level of ethical risk, but if we scraped a bunch of TikTok videos of teenagers, and scraped all their comments, it’s a different ethical question,” Hickey said. The key is determining when scraping is a needed tool. “We should not bow to the pressures and the threats out there.”

Additional Resources

Tips for Mining Social Media Platforms with Henk van Ess

Maximizing Social Media in Your Newsroom: A Tipsheet on Distribution and Engaging Audiences

GIJN Toolbox: CrowdTangle, Echosec, and Searching Social Media

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.