On January 9, masked gunmen interrupted a live news broadcast at the TC Televisión station in the Ecuadorian coastal city of Guayaquil. Image: Screenshot, TC Television

Surge of Violence in Ecuador Threatens Accountability Journalism

Read this article in

Ecuador has been rocked by explosions, kidnappings of police, and prison disturbances since early January, further threatening press freedom in the South American country.

Authorities have blamed the outbreak of violence on high-profile criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking while taking unprecedented steps to bring the security crisis under control.

On January 9, shortly after masked gunmen interrupted a live news broadcast at a television station in the coastal city of Guayaquil, Ecuador’s president Daniel Noboa declared an “internal armed conflict” in the country.

Noboa, who began his term in November, ordered security forces to “execute military operations to neutralize” several armed groups the government has classified as “terrorists.”

He had already imposed a nationwide state of emergency, including nightly curfews and limits to the right of assembly, after the leader of the Los Choneros gang escaped from a high-security prison. The leader of the rival Los Lobos gang escaped from a separate prison the day after.

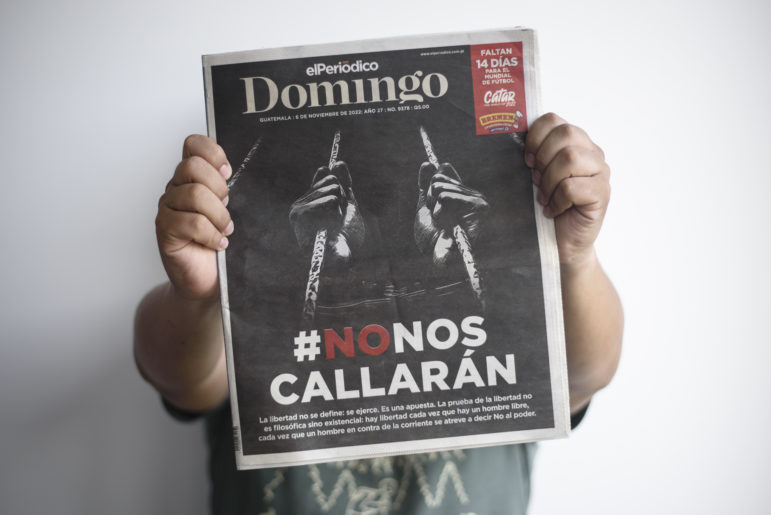

The recent events have compounded the risks for journalists in Ecuador, a country which has also been marred by recent political violence. In August, less than two weeks before the first round in a special election to choose the new president, former investigative journalist and presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio was assassinated while leaving a political rally.

The US-based Committee to Protect Journalists issued a special report in June warning that a “perfect storm” of political turmoil and rising crime was emperilling journalists’ safety. Already this year, one Ecuadorian journalist fled the country, following nine others in 2023, according to Fundamedios, a nonprofit that advocates for press freedom. The journalist, whose name was withheld for safety reasons, received threats for months after reporting on irregularities in public contracts.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) spoke with Paúl Mena Mena, an investigative journalist with national newspaper El Universo and an ICIJ member, about the state of press freedom in Ecuador and the impact on accountability journalism in the region.

Q: Can you tell us briefly about what has happened in Ecuador in the last couple of weeks?

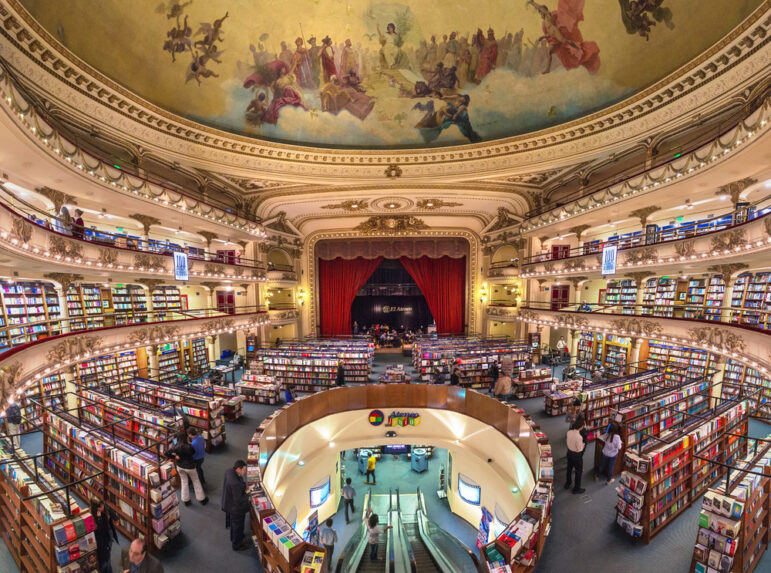

A: President Daniel Noboa declared an internal armed conflict in our country. He has identified 22 terrorist groups that have become, with this declaration, military targets. This decision comes after a wave of violence in the country. It was not the worst wave of violence we have experienced in recent years, but it was the most shocking. The country — and the world — saw live how a little more than a dozen young people, including teenagers, took over the TC Televisión facilities in Guayaquil, while it broadcasted the last part of its newscast. Later the police were able to subdue them and free the hostages they were holding captive, including journalists.

Q: How does this affect the work of journalists and, more generally, press freedom in the country?

A: The atmosphere here in Ecuador, among journalists, is very fearful and I worry that this is causing a lot of self-censorship. That fear has been growing since 2018, when a dissident group, the Oliver Sinisterra group, kidnapped three journalists from El Comercio who were later murdered.

The situation for journalists has also worsened due to the economic crisis, the hit of the pandemic, and the precariousness of the economic situation of the media due to the change in the business model with the digitalization of the media. For example, Diario El Comercio has closed its doors. Since 2021, constant waves of violence have been reported, especially in prisons, where there have been massacres of dozens of prisoners and, parallel to that, threats against journalists who cover this violence.

In 2022 there was the murder of journalist Gerardo Delgado, which we later learned was planned by drug-trafficking groups. In 2023, for example, there were nine journalists exiled from Ecuador because their lives were at risk — journalists who covered the public safety beat. Already this year, in these few days of 2024, we have a journalist who left the country.

This weekend I was talking to journalists from a coastal city where Los Lobos [the largest organized crime group in Ecuador, according to the authorities] have total hegemony and they told me of their helplessness at not being able to publish much information because it is very dangerous for them. Their lives would be in danger…

I think what this environment of fear is doing, is that the majority of the media is dedicated to just documenting the violence and repeating the official statements. Very few journalists investigate violence in depth to find out why [it] happens and who are the actors, both within the state and outside the state.

I think what this environment of fear is doing, is that the majority of the media is dedicated to just documenting the violence and repeating the official statements. Very few journalists investigate violence in depth to find out why [it] happens and who are the actors, both within the state and outside the state.

I think this is a good time to think about transnational collaborations since Ecuador is suddenly the most visible point of violence, due to all these waves and the takeover of TC Televisión, but the roots of this problem go beyond the borders of Ecuador.

Q: Could you describe the work logistics right now? What are your working conditions? Have you taken any special precautions?

A: Once we saw the armed takeover of TC Televisión live, almost all the media outlets, if not all, redoubled their safety measures. Some media outlets immediately opted for remote work.

Since then, journalists have been doing their work from home, and others, who have to do daily coverage on the streets, go out with bulletproof vests and helmets. I have seen some reports from colleagues who have toured neighborhoods where entry was already prohibited for many months, especially in Guayaquil and surrounding cities. In many neighborhoods, not even the police could enter. Now with this declaration of internal armed conflict, colleagues have been able to access those territories with all the security equipment, and protected by security forces.

Q: As for your journalism, what are your biggest fears or worries?

A: I believe that President Noboa has the support of the citizens in his decision to declare an internal armed conflict since, today, the majority of Ecuadorians are victims of extortion from criminal groups. It is a crime that is very widespread in Ecuador and citizens are tired of it. But putting safety policy in the hands of the armed forces raises many concerns since there is a lot of evidence that drug trafficking groups have inserted themselves into the security forces.

In Ecuador, we do not have a system of control over the security forces. Although there are civil authorities in charge of these institutions, I believe that President Noboa has made the mistake of appointing people with an unsuitable profile to [oversight] positions.

As minister of defense, we have an entrepreneur in private security. We do not have a titular interior minister — the government minister is in charge of the interior ministry and at the same time the government minister is the president’s personal lawyer. At the head of the SNAI, the institution in charge of prison control, is a businessman whose economic activity is very far from the issue of security. So there are no civilians with the ideal profile in command of the security forces institutions. I am also concerned about the fact that [President Noboa’s] response authorizing the use of force… is going to lead to more violence. And I am waiting for the response from organized crime groups.

There are also information gaps… There was always talk of 11 groups and suddenly 22 terrorist groups appeared in the president’s decree. So we don’t know clearly what happened there — if the police hid information from us about the identity of all the groups, or what are the criteria with which the government is considering certain groups terrorists.

We see in other countries, after declarations of war against drugs, there have been records of false positives [such as civilians killed], and mass graves of unidentified corpses for which no one takes responsibility.

How is this new reality changing the focus of your investigations?

The truth is that I don’t like to talk about investigations, especially for reasons of rigor and journalistic method, but what I can say is that it is increasingly common that when one investigates the most dissimilar topics, one comes across activities of criminal groups linked to drug trafficking. It has happened to us while investigating issues of public works or the purchase of medicines, public procurement in general, or attention to basic citizen services. It is because these groups are taking over more and more of the country’s formal economy. So this represents a challenge for journalists. I believe that you can cover any beat or specialize in any topic but it is increasingly necessary to understand the functioning of organized crime and money laundering, and also to reinforce the safety plans, both digital and physical. That is now something you cannot do without in Ecuador.

This post was originally published by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and is reprinted here with permission. The conversation was translated from Spanish by the ICIJ and edited for clarity.

Brenda Medina is an investigative reporter for ICIJ. Prior to joining ICIJ, she was a senior reporting fellow at ProPublica, in New York and worked for the Miami Herald/el Nuevo Herald. At the Herald, she covered local government and immigration and worked on investigations about public corruption, housing, and labor issues. Originally from the Dominican Republic, she studied journalism and international studies in Tampa, Florida.

Brenda Medina is an investigative reporter for ICIJ. Prior to joining ICIJ, she was a senior reporting fellow at ProPublica, in New York and worked for the Miami Herald/el Nuevo Herald. At the Herald, she covered local government and immigration and worked on investigations about public corruption, housing, and labor issues. Originally from the Dominican Republic, she studied journalism and international studies in Tampa, Florida.