Image: Shutterstock

Best Practices for Working With Mass Shootings Data

Tragically, mass killings by civilians happen in many countries, from Yemen to Honduras and Norway, and include profit-motive shootings, familicide, tribal conflict, and racist hate crimes. Meanwhile, several nations in Latin America and the Caribbean — including El Salvador, Colombia, and Venezuela — feature the highest rates of overall firearms homicide.

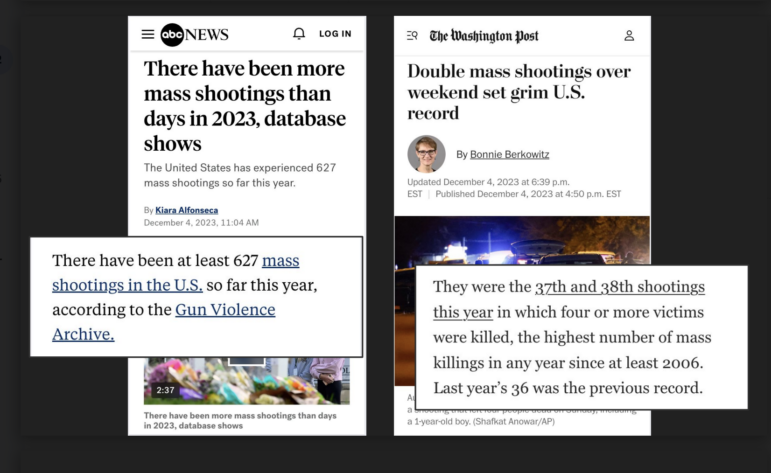

But veteran editors say there is often confusion among data journalists about one particular subset of gun violence — “mass shootings” — which sometimes lead to wildly different numbers between outlets and editions, and deeper confusion among audiences.

For example, even among trusted violence databases, definitions range from “four or more shot and killed or wounded, excluding the shooter,” to “four or more shot and killed,” to datasets that include so-called active shooters who don’t shoot, and others that include other weapons and injuries sustained in the course of fleeing the gunman.

Given the potential for journalists to inform life-saving policy interventions that have been seen in countries such as Australia, experts say it is crucial that investigative and data reporters think carefully about the definition of “mass shooting,” and about the local and international datasets they use — so that they can be consistent and transparent to audiences to retain credibility and impact.

Even more important: investigative and data reporters must not lose sight of the victims — the lives lost or ruined — and on any enabling policies that contributed to the massacre. And never glamorize the shooter or their grievances — perhaps mentioning the shooter’s name only once, and no more.

How to Compare US Mass Shootings to Other Countries

Though mass firearm killings can happen in numerous countries, data shows that regular civilian mass shootings of strangers outside of conflict or gang zones is a phenomenon confined to only one country: the United States. (The US is also a striking global outlier for gun suicides — accounting for an astonishing 44% of all firearm suicides recorded worldwide, according to data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.)

Reporters have access to data and graphic material that reveal spectacular gun violence contrasts between the US and other developed countries, in particular. While data journalists often use 3 or 4 percentage-point contrasts as compelling story angles — some US gun statistics are hundreds or even thousands of percent higher, or worse, than other countries.

Meanwhile, reporters can also find data on other violence risk factors, such as rates of mental illness, which show no such contrasts — and also easily show data that reveals that America’s gun ownership rate is, for example, about 22 times higher than in the European Union. Yet only a small number of data journalists, such as UK-based Kara Fox at CNN International, regularly show these jarring country-by-country contrasts in major media.

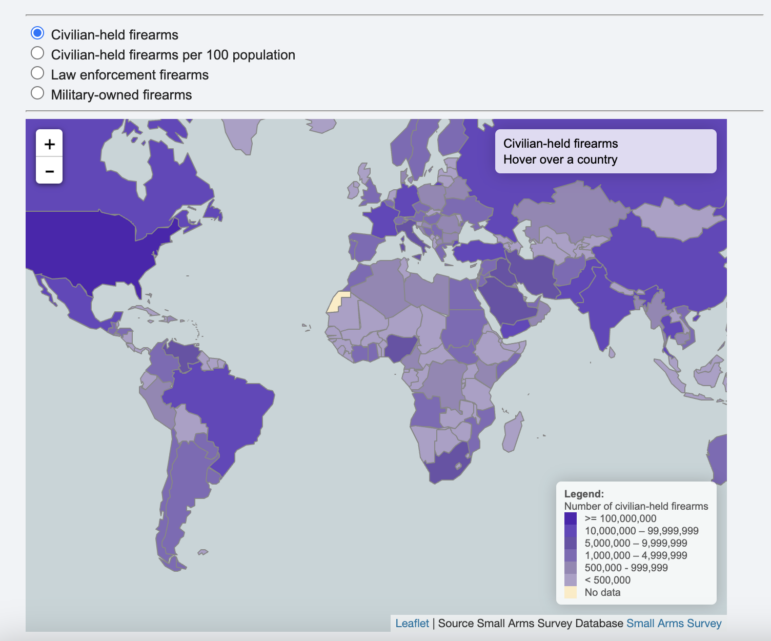

“We at CNN have done some version of this global comparison story five times, because the data is glaring, yet is rarely used or understood,” said Fox. “The Global Burden of Disease database from IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation) is where you want to look for these comparisons. It’s by no means exhaustive, but you can choose a category and country and compare it, for example, to the US.” Fox also uses data from a trusted global mass shooting researcher, Jason Silva, and from the Global Firearms Holdings dataset within the Switzerland-based Small Arms Survey, which can be filtered for “civilian-held firearms.”

She added: “We have looked at mass shootings, firearm homicide rates, and suicides, but we have not yet dug into the mental health country comparison aspect yet, so that’s also an opportunity for someone out there. There needs to be a more global comparative look at this data, because it exists — and I’d also encourage data researchers who look at global comparisons to reach out to journalists.” (Fox showed, for instance, that the US private gun ownership rate is more than twice that of the next-highest country, Yemen — a nation caught up in a long-standing civil war.)

The Global Firearms Holdings dataset from the Switzerland-based Small Arms Survey. Image: Screenshot, Small Arms Survey

How to Find and Present Mass Shooting Data

In a session on “Reconsidering Data on Mass Shootings” at the recent 2024 NICAR data journalism summit, an expert panel shared tips on how to find and deal with data on these tragic and often avoidable incidents.

The panel included Jennifer Mascia, senior news writer at The Trace, Simone Landon, a graphics editor at The New York Times, Larry Fenn, a data journalist at the Associated Press, Lindsey Cook, a deputy editor for data journalism at The New York Times, and John D. Harden, a data reporter for The Washington Post who covers crime and mass killings.

For suspected mass shootings in the US, the panelists recommended the following databases.

- The detailed Violence Prevention Project database, which includes data going back to 1966, as well as numerous data variables for the shooters involved.

- The Gun Violence Archive, which includes live updates, and a broader definition of mass shootings. “The Gun Violence Archive is a nonprofit that basically scrapes news and police reports, and has created what is the closest thing we have to a real-time database of people who get shot in the US,” Mascia explained.

- The K-12 Shooting Database, which includes any gun incident on school campuses.

- The FBI Active Shooter database and the Active Attack Data dashboard, which also includes data on how incidents were “resolved.” However, government databases often lag real-time statistics substantially. For example, the FBI Active Shooter register’s most recent full-year of data is from 2022. Tip: Speakers suggested that officials at the Active Attack database may supply additional spreadsheet information, if asked.

- The Mass Killings Database, from AP, USA Today, and Northeastern University, which also includes data from medical examiners’ reports, court documents, and prison reports.

Again, different organizations and government agencies can define mass shootings differently.

“In the US, there is no federal definition for mass shooting, and the criminal code has no distinct mass shooting offense,” Mascia explained. “The FBI officially defines ‘mass murder’ as at least four people murdered in a single event, which doesn’t specify what weapon was used … and the Department of Homeland Security has a definition for ‘active shooter’ — but that’s not based on body count but location, and includes somebody who just attempts to kill somebody in public.”

These two stories by ABC News and The Washington Post — both published on December 4, 2023 — describe a total of 627 mass shootings and 38 mass shootings, respectively, in the US during the same period. Neither was technically incorrect — but the vast discrepancy illustrates the need for careful thinking and clear definitions for mass shooting data. Image: Slide, NICAR 2024

To deal with data on civilian mass shootings, the panel recommended that reporters take several steps.

- Try to “unlearn” assumptions we may have from spectacular events described in mass media. For instance, statistically, most mass killings do not happen in public places, but rather in and around private residences. Likewise, most child victims of mass shootings are shot at home, not at school. And while they are an alarming and largely new phenomenon, mass shootings account for only 1.5% of gun homicides in the US, and are an even smaller share of gun violence in most other countries.

- Be consistent and transparent with your own definition — and check to see whether your research sources and databases use the same. “If you pick a definition, stick with it,” advised Harden. “You don’t want to go with ‘three-or-more,’ if ‘four’ was your prior starting point.”

- Note that some of the most reliable research on raw mass shootings data is curated by a small handful of individual (and media-friendly) researchers — such as Jason R. Silva, an assistant professor of sociology and criminal justice at William Paterson University who looks at global data, and James Alan Fox, a professor of criminology at Northeastern University, who co-launched the Mass Killings Database. Note also that academic researchers tend to use strict or conservative definitions — so ask them if they can synthesize data to fit or at least fact check your own definition. Said Fox: “Jason Silva was the first person whose data we were comfortable using, who had looked at mass shootings on the same scale across all countries, including the least developed countries and those involved in conflict.”

- Don’t minimize the horror and personal impacts of mass shooting incidents that don’t result in several deaths — but limit the use of the phrase “mass shooting” to incidents that meet your exact criteria. “We at The Trace are careful not to just throw the term ‘mass shooting’ around,” Mascia explained. “What if just three people were shot? Maybe this was an active or ‘public shooting.’” Harden added: “Also, you don’t want to overwhelm or numb your audience.”

- Consider aligning your definition with the model already used by major data sources you are likely to use in future — such as the AP’s Mass Killings Database. Said Fenn: “The AP keeps a mass killings database that can be filtered to shootings. The definition we use is four or more victims, excluding the offender, excluding unborn children, in a 24-hour period — including all weapon types. It’s a public database.”

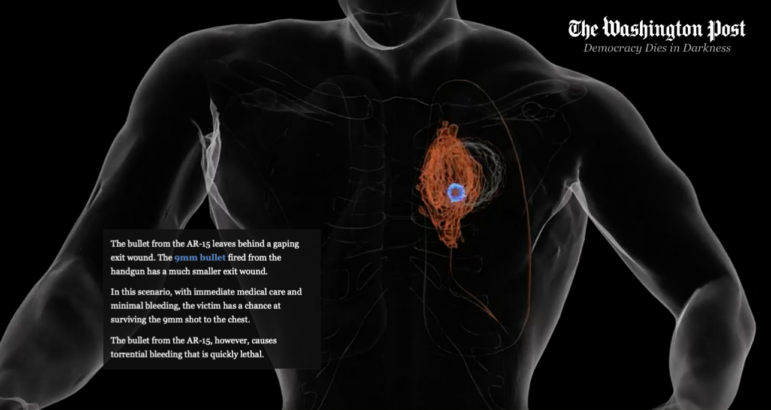

- Pursue human and medical follow-up stories which show the life-long physical and psychological scars of survivors — and set your reporting calendars to revisit those survivors on anniversary dates, to underscore the enduring, devastating impacts of gunshot wounds and experiences. One standout example: this 2023 Washington Post visual investigation that explored in graphic, physiological detail the horrific damage an AR-15 round can do to the human body.

- Look for both the offenders’ motives and enabling factors.

- Remember that mass shootings represent a small subset of a much larger issue. “They represent a small percentage of firearm violence that includes gun homicides and gun suicides,” noted Landon. ”Yes, they are spectacular and awful, and only happen in the US for various reasons, but I find it important to get newsrooms to look more broadly, as they are all interrelated phenomena.”

Landon said the Global Terrorism Database has tracked mass shooting events around the world in the past, but that recent or current global data remained a challenge for data reporters.

Mascia agreed. “International stats on shootings are not easy to come by. There have been good efforts that have since run out of funding,” she noted. “Journalists need to know that a domestic shooting can turn into a public one very quickly. A lot of these shootings come out of grievances, or workplace issues, or families.”

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s senior reporter. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s senior reporter. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.