Victim of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre found on mountain route used to escape. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Investigating War Crimes: Introduction

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: What Is Legal in War?

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Environmental and Property Damage

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Banned and Restricted Weapons

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Combatants and Others Engaged in Hostilities

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence and Information

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Command Structures

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Tracing War Criminals

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Finding the Missing

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Documenting with Photo and Video

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Interviewing Victims and Survivors

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Physical and Digital Security

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Self-Care for Covering Traumatic Events

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Resources and Tipsheets

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes – Video Recording

Chapter Guide Resource

GIJN Launches First E-Book — Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Mass atrocities committed by government soldiers; villagers forced to flee as their homes and crops are destroyed by government troops; indiscriminate bombing of schools and hospitals; widespread rape; the torture of prisoners of war; systematic ethnic cleansing; and the use of child soldiers — these are but a small handful of possible war crimes investigated by journalists.

The wanton killing and abject treatment of human beings during times of war and conflict, and the attendant horrors of such violence, demand accountability. Journalists have a critical role in reporting and investigating war and conflict. Shining a light on the practices of those who wage war, asking tough questions, digging to find evidence and exposing lies and propaganda, and what is really going on — are a critical part of the work of investigative journalists, work that complements the work of war reporters, human rights researchers, photographers — and legal authorities.

Reporting and investigating war and conflict are critical, whether or not a war crime may have been committed. And as Ukrainian investigative journalist and contributor to this guide Valentyna Samar notes: “It is impossible to write professionally about war without basic knowledge of the laws and customs of war.”

In war, it is the existence and enforcement of laws that enables the prosecution of war criminals. In popular usage, the term “war crimes” is broadly used to describe horrific acts of violence carried out in wars and violent conflicts, acts that seem to violate accepted international rules of war. However, “war crime” is also a legal term with a prescribed meaning spelled out in international treaties that only applies to specific, serious violations of international humanitarian law. It’s essential to understand that violations of the laws in war go beyond war crimes committed by individuals, and include violations by states and others. As further elucidated in Chapter 1 of this guide, the following laws apply in armed conflict:

- International humanitarian law (also known as the laws of war or laws of armed conflict), regulating the actions of states and non-state armed groups that are parties to a conflict.

- International criminal law, regulating the responsibility of individual perpetrators of international crimes.

- International human rights law, regulating the obligation of states (and in some cases non-state actors) towards individuals within their territory and/or jurisdiction, although its application may sometimes differ in armed conflict.

- Domestic laws of the states.

- Other international laws and agreements entered into by the state, although their application may differ in armed conflict.

Understanding how arguments are made about context and intention are critical: killing an innocent person can be a crime of manslaughter, murder, a war crime, part of a crime against humanity or an act of genocide. Unfortunately, in war, some civilian deaths can also be consequences of lawful acts, and are not always war crimes or violations. Horrific atrocities that may seem to be obvious “war crimes” can be highly contested: the United States military’s bombing of a Médecins Sans Frontières trauma hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan in 2015, still under debate, is a case in point, and again illustrates the complexity of legality in war and conflict. (An internal US military investigation blamed the bombing on a AC-130 gunship air crew’s “human error” and “misidentification” of the target.)

In 2015, the US military bombed a Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan. Whether or not the act constituted a war crime is still under contention. Image: Screenshot, Médecins Sans Frontières

Investigative work by journalists is painstaking and can take months, even years, and it must be of the highest standard, especially if it is to stand up in a domestic or international court of law. Yet what is lawful in war is not the same as what is morally right, and reporting and investigating war and conflict are critical, whether or not a war crime may have been committed. The laws governing war and conflict are important but only part of a wider picture of accountability. Many practices considered to be legal still demand investigation and scrutiny — and journalists need to try to hold actors politically accountable for the suffering in war. The journalist’s role in reporting on possible war crimes is not to carry out a judicial investigation and there are real tensions between the roles and responsibilities of journalists and those of prosecutors and legal investigators – the protection of confidential sources; the importance of independence; and the need to publish, are but three of these examples.

Understanding what is going on in the middle of an armed conflict is rarely easy. When observing or reporting an incident, it will usually not be possible for a journalist to establish the existence or not of a war crime. Journalists have not been trained to make the necessary distinctions between legal, illegal, and criminal acts. In addition, all individuals (including those accused of war crimes) have the right to a fair trial, and the existence of a crime may only be established by a court after an effective investigation and trial have been carried out. What may seem to be an obvious crime may, in fact, not be because very specific legal criteria must be met, or because a state is not party to a relevant treaty.

Yet, at the very least, accurate understanding of the applicable laws can ensure and improve credible reporting, and raise awareness of potential violations. This in turn can put pressure on governments and those with international responsibilities to investigate and prosecute perpetrators. Good reporting of possible war crimes or patterns of crimes may be the only way the international community becomes aware of them and can serve as the first step to bringing the perpetrators to justice. When states fail in their responsibility to do so, it is often the work of journalists and civil society to ensure these acts do not get covered up and go unpunished. Ultimately, credible reporting can lead to further accountability and contribute towards combating impunity. Accurate reporting can also matter to individuals affected by acts in conflict, as well as their families and relatives. In addition, journalists, because of what they witness and document, may wish to submit evidence of potential war crimes to legal authorities. There is increased interest from journalists in cooperating with courts and others, and in understanding the very high standards of evidence required.

The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) in Bosnia has led the way in using DNA as a first step in the identification of large numbers of persons missing from armed conflict. By matching DNA from blood and bone samples, the ICMP has been able to identify over 17,000 people who were missing from the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia countries and whose mortal remains were found in hidden graves. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

The scope of this guide is necessarily limited and its aim is to provide useful context and practical advice to enable better investigations. It does not attempt to assess the relevant laws and judicial institutions, nor the commitment and effectiveness of states and international bodies to implement those laws and prosecute those responsible for carrying out crimes in war and conflict. It provides tips for journalists on how to collect evidence that could be submitted to legal authorities, though because the laws of evidence will be different in every state, and in every international court, contacting relevant experts will often be the best strategy. The guide also recognizes that this is a choice not all journalists will make. Finally, there are many other crimes related to war and conflict that need investigation by journalists that are beyond the scope of this guide, including war profiteering as well as corruption in defense procurement and foreign assistance disbursement, to name a few.

With that in mind, we at GIJN are pleased to offer this Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. This guide is to help media that are documenting conflict and its outcomes. The work of investigative reporters and human rights researchers is vital to holding the perpetrators accountable, a long and fraught but necessary process of safeguarding evidence of atrocities, preserving the testimony of survivors, and building a trail of accountability. We have asked reporters with deep experience in investigating war, human rights experts, and lawyers, to offer their advice about how to tackle these complex issues. We’ve also taken account of developments in technology, such as satellite imagery and social media, that are changing how journalists cover war today.

In addition to this introduction, the guide has 16 chapters as well as a preface by Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Nadia Murad.

Acknowledgements

- This guide was a collaboration of investigative journalists, writers, legal advisers, and subject-matter experts across many continents, but it would not have been possible without the generous funding of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation.

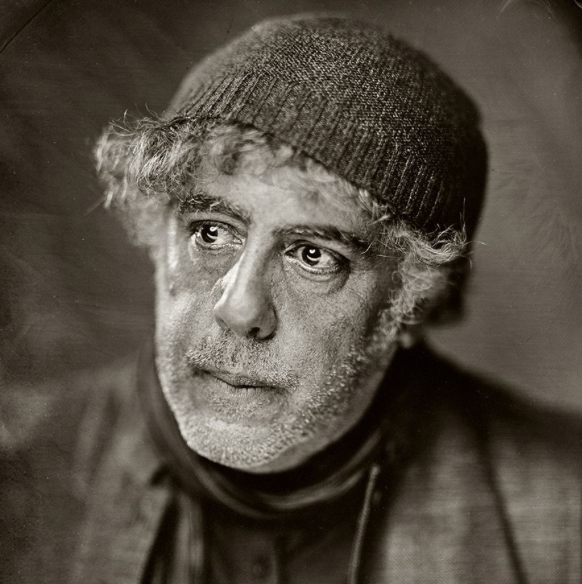

- A special thanks goes to photographer Ron Haviv, of The VII Foundation, for contributing dozens of compelling images from his archives to help illustrate the guide and make clear the impact of war and war crimes. In addition, he contributed an insightful chapter on how to use photos and video to document atrocities and possible war crimes. Thanks also to Ali Arkady, Ed Kashi, Christopher Morris, Maciek Nabrdalik, Franco Pagetti, Scott Peterson, and John Stanmeyer for use of their photos. Robert Dannin also played a key role in facilitating the contribution of these photos.

- To ensure the entire guide carefully considered international human rights law and other relevant legal precedents, a special thanks goes to Dr. Claire Simmons for her expert advice throughout the guide’s production. In addition, University of London Special Lecturer Daragh Murray deserves a debt of gratitude for his assistance reviewing aspects of this guide.

- Journalist Olivier Holmey deserves thanks for conducting the “special focus” interviews for this guide. Additional appreciation goes to those who generously shared their time and expertise in these interviews: Azmat Khan, Ruth Omar, Sheila Kawamara Mishambi, Raji Abdul Salam, Valentyna Samar, and Pascale Bonnefoy Miralles.

- Margot Williams provided invaluable assistance by diligently fact-checking the guide.

- Nobel Peace Prize-winner Nadia Murad generously contributed her personal story and explained why investigative journalists play a key role for survivors of atrocities like herself.

- A number of GIJN staff played key roles in bringing forth the guide from the idea stage all the way through to publication. GIJN’s Arabic editor Majdoleen Hasan helped shepherd the guide as project manager, along with continual oversight, input, and guidance from GIJN Program Director Anne Koch. GIJN Resource Center Director Nikolia Apostolou was also instrumental in the guide’s publication. GIJN Executive Director David E. Kaplan played a key role in assuring the project stayed focused on its mission and in leading it through to publication.

- This guide also would not have been possible without the tireless editing and coordination on the part of GIJN’s editorial staff, including senior reporter Rowan Philp, associate editors Laura Dixon and Alexa van Sickle, and managing editor Reed Richardson.

Anne Koch is program director at GIJN. She worked as a broadcast journalist and executive for more than 20 years, mostly for the BBC, where she served as deputy director of the BBC’s English World Service, executive editor of its flagship radio news and current affairs programs, and editor of the World Tonight.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than 25 conflicts and worked in over 100 countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than 25 conflicts and worked in over 100 countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.