Ron Haviv, celebrated war photographer of the VII Photo Agency, under sniper fire from rebels of the Northern Alliance, during the surrender by the Taliban of the village of Maidan Shar, Afghanistan, 2001. The stand-off at Maidan Shar — 30 kilometers southwest of Kabul, on the strategic Kandahar road — lasted one week, with 2,000 Taliban finally surrendering. Image: Courtesy of Scott Peterson

Investigating War Crimes: Documenting with Photo and Video

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: What Is Legal in War?

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Environmental and Property Damage

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Banned and Restricted Weapons

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Combatants and Others Engaged in Hostilities

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence and Information

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Command Structures

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Tracing War Criminals

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Finding the Missing

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Documenting with Photo and Video

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Interviewing Victims and Survivors

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Physical and Digital Security

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Self-Care for Covering Traumatic Events

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Resources and Tipsheets

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes – Video Recording

Chapter Guide Resource

GIJN Launches First E-Book — Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

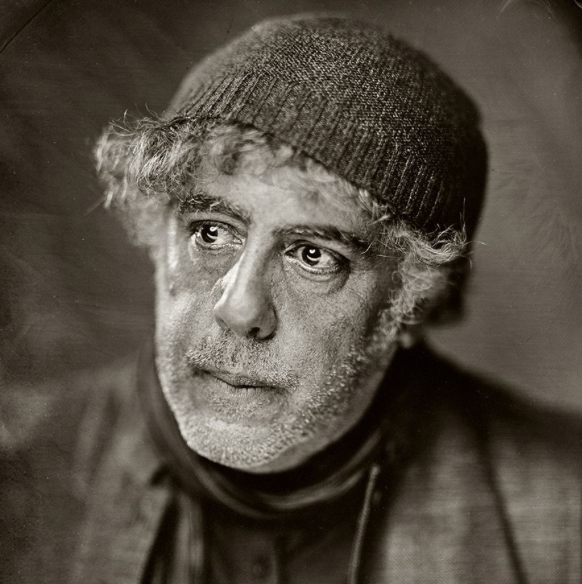

Editor’s note: This advice from veteran conflict photographer Ron Haviv — co-founder of the VII Photo Agency and The VII Foundation, who has covered more than 25 conflicts — reflects an edited transcript of his insights from an extended interview with GIJN senior reporter Rowan Philp.

The role of the visual journalist, photographer, or videographer is different from other journalism roles, in that we always have to actually see what is happening. We have to be there – be upfront, as witnesses. But, like all journalists, we also need to understand the story, and the players involved. We need to rapidly develop relationships with local sources to know what’s happening, and to be able to anticipate events.

Technology has changed over the years, and so too have conditions in conflict zones. All people in the theater of conflict, including soldiers, are more sophisticated about how photography works, so they aren’t fooled if you just delete the image on the back of your camera. In some regions in the 1990s, your sheer presence and the presence of your camera, representing the Western world, could cause whatever was happening to stop. Nobody really cares about that anymore.

Our responsibilities have changed also. Given that photographers are often the first outsiders on the scene in conflicts, it is now increasingly expected that we not only provide the visuals, but that we should provide the context as well. So when you come across a scene in Bucha, Ukraine, where two men are lying dead in a front yard, the older way of working might have been: “Take the best photograph possible, document the situation, and caption it: ‘Two men lie dead in a Bucha front yard.’” But now I think it’s our responsibility to get the context and the backstory — talk to multiple people, collect what documentation you can, gather relevant facts, and contact numbers — and create a fuller caption and context for that image.

You need to be able to adapt on the fly, to be able to take advantage of what people and even soldiers want from you — making sure you’re always being ethical, and reporting with integrity.

Preparation

The information and gear you need before going to document conflict.

Try to consume as much information as possible ahead of time — from traditional media, like, say, The New York Times or the Guardian; from your colleagues; from trusted military press officers, from local media; from NGOs; and from local journalists or producers, sometimes known as fixers, that assist you.

Of course, you already need to have formal hostile environment and first aid training (HEFAT). [See more on this training below]. It’s also a good idea to identify and join the WhatsApp or Facebook groups of journalists already located where you’re headed.

I have a basic kit I take on foreign assignments — cameras, computer, satellite phone, etc. — and an extra set of gear specific to the country and the story. If I’m going to a front line, I’ll need X, Y, and Z; if I’m only going to France to cover the protests, I’ll need a different set of gear.

Ask colleagues who’ve been there about the items they needed, and think about the nature of the place you’ll be visiting: Will power likely be out? Are there disease risks?

If I’m going to an impoverished region, I’ll need to deal with more medical issues, because I’ll be more isolated than if I’m going to a European city.

For instance before traveling to Libya for the Arab Spring, I packed a flak jacket, ballistic [body armor] plates, and a satellite phone; I had a first aid kit and probably some water purification equipment, like a small filtration straw. Take extra batteries; equipment to get power from a vehicle, maybe solar power. Try to be as self-contained as possible just in case.

Make sure you have communication back-ups. Luckily, the days of $40-per minute sat-phone calls are over; now you can call for $2 per minute, or use them to transmit your images, but, amazingly, there is often some kind of cellphone coverage almost everywhere you go.

Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko speaks to the media near the frontline in Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Access

Embedding may be controversial, but it remains a key avenue for photographers to possibly document war crimes.

The help of fixers, also known as local producers, is incredibly important, both in terms of helping you with things like language translation, but also for access to the military or paramilitary commanders and politicians and so on, to gain permission to the front lines. Developing relationships with local people is essential. Being identified as Western press — with a sign that says PRESS, translated in the local language — can be helpful in situations where people realize you’re the mechanism for telling their story. But it can also be difficult, because you are representing the outside world, and they might not want you there to bear witness. At that point, you might not want to be identified with press markings. Each situation will need its own rules and analysis.

You need to figure out how to get to the event — whether that’s something as simple as embedding with a Western military unit, which can be a process involving meeting commanders, and having your editors write letters on your behalf. It also depends on personal relationships: from developing a good relationship with a press officer in Ukraine, for instance, or becoming friendly with a unit in Ukraine to work more independently.

There are rules that can be broken, and rules that can’t. Within realistic limits, you can make yourself less visible. But even if you’re just using an iPhone, you’re still pointing something at somebody, so being invisible is difficult. Depending on your ethnicity and gender and so on, you will either blend in or stand out, and you have to take that into account. Individual photographers need to consider how perceptions of you and where you’re coming from affect your relationships in the field, and affect your ability to work effectively in various contexts.

For many journalists, and for the public, journalists embedding within military units, like some within the US Army, gained a negative connotation during the second Gulf War. But embedding is essential to what every photographer wants to do, whether it’s spending time with the family of refugees, or a politician attached to the conflict. You want to maintain a presence until your subject don’t even remember you’re there, so they will go about their business naturally. This is often the only way we’ve been able to witness war crimes up close. When I spent time with Arkan’s Tigers in Bosnia, with the permission of the commander, I was basically just present. Yes, they didn’t want me to take certain photographs, but because I was there, and “part of their group” and documenting what they were doing, they looked at me in a different way.

Never go into an assignment thinking: “I’m going to embed with them til I catch them committing a war crime.” Instead, your mindset should be: “I’m going to see what they’re going to do, and document whatever happens in front of me.”

Tools

War photographers actively cooperate — and apps that connect them are essential tools.

In the past few years, specific Facebook groups involving various journalists have been launched, where the members contribute knowledge and lessons learned. During the Russian war with Georgia, there was a similar group where many journalists were sharing information that was extremely helpful.

Fast forward to Ukraine, and there is now incredibly sophisticated sharing of information between photojournalists. This also includes the Ukrainian government, or pro-Ukrainian activists, saying, “This battle is starting here,” or “Shells just landed in this neighborhood.” That’s all available through various WhatsApp groups, Telegram channels, and Signal groups. This was very helpful information for Ukraine — especially during the first month of the war, when different parts of Kyiv were being attacked, and you had to get there as fast as you could, to document the impact. Like everything, you really need to start by asking your colleagues and peers for these groups – especially in the world of photography, which is incredibly generous and helpful to the younger generation.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF) have various services that help, and a new WhatsApp channel from CPJ, called Chat CPJ, helps walk photographers through risk assessment, safety training, pre-assignment support, and so on. That’s especially helpful for newcomers.

Techniques and tools for conflict photography are also discussed and taught throughout the courses we offer at the VII Academy, which are free of tuition fees.

Safety

Crowdsource and survival training — especially mental retraining — are safety best practices.

I would not work with anybody, or even stand next to anybody, in any risky situation, who has not gone through a proper hostile environments training course (HEFAT). These courses (CPJ has a long list of HEFAT providers), are absolutely essential , and not just for the vital importance of understanding trauma first aid, (which most people really don’t know). This training differs greatly from understanding war and conflict on TV and the movies. There, you might see someone react by saying, “Oh there’s gunfire, let me go hide behind this car door,” without realizing bullets will go right through a car door. These training courses retrain your mind to survive. So, when bullets are flying, you don’t stand up to see where they’re coming from, which is a normal reaction for many people; you don’t cross a sniper alley one after another, like in the movies.

This applies to places like refugee camps, too — any place where kidnapping or militias are prevalent, you really need one of these classes. There are organizations like the Rory Peck Trust and the ACOS Alliance that will help freelance photographers find funding for these courses. Many of these courses will have slots available for freelancers that are either heavily discounted or free, so there really shouldn’t be any excuse to not have this training before going to a war zone.

CPJ has many good resources as well, like a guide to moving personal protective equipment across borders. But real-time information is central to safety, so trust the information from fixers and fellow journalists on scene in the conflict.

There is also a major psychological and emotional aspect to safety. Academic studies led by Dr. Anthony Feinstein have found comparable levels and effects of PTSD between war journalists and soldiers and police. These findings have helped to de-stigmatize PTSD in newsrooms. It’s also encouraged managers to pay more attention to staff coming back from war zones, be more conscious of telltale signs of PTSD, and offer treatment when needed. As somebody who has suffered from PTSD, I can say treatment is very helpful, and nothing to be ashamed of, and organizations like the DART Center have important resources to help reporters handle these impacts. PTSD can be cumulative — it could take five trips before it presents — and it doesn’t have to involve witnessing conflict or war crimes.

Captions

The responsibility for providing context for images rests with the photojournalist.

Photographers can certainly collaborate with reporters on captioning if they’re together, but the caption is absolutely the responsibility of the photographer. Accurate, contextualized captions are paramount. For starters, if they are misleading, the image will be misunderstood. We are photojournalists, after all, so the who, what, why, when, and how should be in the caption, if possible. Guessing should not be. If there is a backstory, that should be added too, so there is context. The work we are doing — especially around war crimes — will likely be immediately attacked by someone, claiming it’s not true, or wasn’t perpetrated by their people.

Don’t overlook updating your captions. In Bucha, for example, I was among the first group of photographers who found men executed behind a building. Access to Bucha had just opened up, and nobody really knew what had happened there, so we wrote what we knew. Later, The New York Times did a substantial investigation. They put together who the men were, what happened to them, and by whom — and so our initial captions needed to be updated with that new, verified information.

If you’re wrong in your caption — and you’re working for a well-trusted, narrative-establishing news service like the AP, or Reuters, or AFP — it can be very hard to correct information once it’s out there and republished. If you’re the first person from the outside world at the scene of a possible war crime, it’s crucial to gather as much metadata as possible, depending on the gear you’re using. If your camera doesn’t do it, use your phone to get a precise GPS location, or simply take an extra image with your cellphone.

Documenting Potential War Crimes

Why getting the perpetrator and the victim in the same frame is the ultimate goal.

I’ve never said to a soldier: “Do you realize you’ve just committed a war crime?” But I will say that soldiers and paramilitary fighters often feel like they’re fighting for a cause – say, a nationalistic or family or religious cause – and believe their actions are justified.

The idea of using photographs to document criminal activity is secondary; it’s more that photographers are the eyes of the public, and document what we see, to bring that to the world’s attention.

With the ethnic cleansing image of the soldier in Bosnia — a militia member in the act of kicking a dying woman — I realized that to defend this photo visually, I needed one of the soldiers, with his insignia, plus victims in the same image. I was just hoping for an image of them walking by the victims; not necessarily with his foot back, about to kick them. But that was a conscious effort, to make sure nobody could deny what the caption was going to say. If it was just the victims just lying there, it would be my word against theirs. This way, it’s much harder to dispute.

Members of Arkan’s Serbian paramilitary group, the Tigers, execute unarmed Muslim civilians during the first battle of the Bosnian war. This image was used as evidence in numerous procedures to indict and convict people of war crimes. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Beyond the value of evidence and public awareness, these images can also provide a form of protection for the victims. A photo I took — of the vice president-elect of Panama being beaten by Manuel Noriega’s thugs — became so well known that it gave the victim, Guillermo Ford, some protection from further attack.

Equipment and Evidence Security

Quickly uploading images to the cloud — and awareness of what’s been published — are important to protect both photographers and what they find.

Digital technology has certainly changed photography. When I was photographing with film, there were points in some conflicts that I got stopped by soldiers angry that I appeared to be taking pictures. Sometimes, they’d take the film out of my camera, pull the film from the canister, and hold it up to the light, and then conclude, ‘OK, there’s nothing on this,” and then hand the camera back, believing I’d taken no images at all. They often had no understanding of how photography works.

When digital cameras first came out, we would just delete the picture on the back of the screen — but, now, combatants are more sophisticated, and know you can recover a deleted picture, so now they’ll just take everything — all your cameras and digital cards. They also know how to search online. So, if you’re sending daily images to a newsroom somewhere and they’re being published, combatants can easily see them. Now, it’s better to upload images to the cloud, so, once there, they can never be removed. Still, there’s a risk you run into a person who doesn’t like your published work, and it can be hard to talk your way out of it.

When it comes to navigating a conflict zone, still image photographers generally have to get a little closer to an incident than a videographer — but we’ve also had videographers standing right next to us in the most difficult situations. They also have the ability to use sound, which can make something that’s not very visual much more dramatic. And with the cellphone camera, it’s obviously much easier now to capture video in very intimate situations.

Documenting protests and war, we still use traditional Digital Single Lens Reflex (DSLR) equipment. But because smartphone camera quality is so high in both video and still image quality, you can have a very small footprint in terms of not having giant cameras in the faces of stressed people. Also, it can make embedding requests much easier.

For a short film I did during the Arab Spring in Libya, I used a DSLR camera for video and stills, and an iPhone for stills – juggling between them, depending on the situation.

Gruesome Imagery

It’s important to keep documenting atrocities – but be mindful to look for images that audiences won’t ignore.

Publishing evidence of possible war crimes can require a delicate balancing act, especially when you’re documenting particularly grisly or shocking events. Recently, The New York Times published a graphic image of a Ukrainian family killed in Irpin on its front page. Lynsey Addario, who took the photo, praised The Times for running it so prominently and I agree, it was quite brave of the Times and rather unusual for US media.

These decisions must weigh respect with impact and the media culture, and sometimes photographers do have to lobby for an image to run where more people can see it. However, you have to accept that images of war crimes or their victims won’t be published every day. That said: editors should also be very careful to not get inured to atrocities and say: “Our audience saw something similar last week, so let’s not bother.” That’s incredibly disrespectful, and also does injustice to the story — which should be: “Why are these killings of civilians continuing?” It’s our responsibility as news media to remind people day in and day out of wrongs that continue to happen.

I wouldn’t say that I alter my framing in anticipation of editing decisions, but I am very conscious about the way I frame via the aesthetics. I’m very aware that some graphic images of a body torn apart is not something most people can deal with. Even if it was published, they might just quickly swipe to the next page, because it’s so horrific. If that happens, the photograph is a complete failure. So, a successful photograph in terms of what could be a war crime will find that moment where the reader will be drawn to that image, making it that much more powerful. I want there to be a relationship between the viewer and the image. The flip side for me is that I’ve been accused of creating “war porn,” and I understand the criticism, but don’t agree with it. I’m trying to make sure the viewer looks at the photographs, because if they don’t, then what’s the point?

Impact of Women War Photographers

There are women doing the same or better work in conflict than men, when, for a long time, photojournalism in war — especially in Vietnam and World War II, with some remarkable exceptions — was dominated by men. Now, the female voice in this space is truly being heard, or better seen, with the work of people like Lynsey Addario, Heidi Levine, and Carol Guzy, who has won four Pulitzer prizes – more than any other photojournalist. These are amazing photographers, with some unique challenges and unique views. In the Muslim world, for example, they get to see a world that men are prohibited from entering, but, at the same time, they can also be treated incredibly poorly in patriarchal societies. On the other hand, sexual abuse and violence is a much greater threat for women photojournalists, and can require an entirely different risk assessment than their male counterparts.

Certainly, at The VII Academy, educational arm of The VII Foundation we are trying to maintain equality for our students between male, female, and non-binary, which we have done to help the next generation, so the world of photojournalism should be closer in balance.

Intervening

Be an “upstander” not a “bystander” if you can — but helping victims is a personal risk judgment call.

There is no set rule for intervening. Yes, you’ll be documenting life-and-death situations that you could potentially influence, but it could be your life or death as well. You have to make a judgment on what you can — and can’t — do and, if so, what is your personal added risk? There have been times when I have been able to help people — in Haiti and Afghanistan, for instance — and there have been other times when I’ve been unable to do anything. In the latter, I’m determined that, at the very least, I’m able to document what’s going on.

For example, when I was embedded with Serbia’s Arkan Tigers in the border town of Bijeljina in Bosnia in 1992, I photographed a Macedonian-Albanian Muslim man named Hajrush Ziberi, who became one of the first prisoners in the war in Bosnia. He was thrown to the ground, and he put his hands up, and essentially asked me, silently, to help him. There was nothing I could do. He was eventually taken into a building, then either fell out or was thrown out of a window, landed at my feet, and was taken into a house, and I never saw him again. I looked for him at the hospital the next day. Twelve years later, his remains were identified by DNA. When I went to visit his family to explain, I expected them to be furious for not helping him, but the first thing they did was take out every publication that had used my pictures of their son, and they said: “Thank you for making his death mean something.” I thought this was just incredible. They felt there was some impact, and, in fact, the photographs were part of a series used in The Hague as evidence of a war crime.

Case Studies

Heightened Risk of Sexual Abuse for Women Photographers

Sexual discrimination and assault remains a greater risk for women photojournalists. During widespread attacks on the press amid the Arab Spring protests in Egypt, I witnessed episodes of sexual violence. I remember how my colleague Chris Hondros and I had to shield a woman photographer to move her through the crowd safely, because she was getting so physically abused by the men.

Embedding in the War in Ukraine

If you look at The New York Times coverage in Ukraine, several of their photographers — Tyler Hicks, David Guttenfelder, Mauricio Lima — are spending time with certain units day in and day out, or are doing a story focused on medical first aid stations, because they think it’s important, even if that means missing out on separate shots elsewhere. There are also a number of freelance photographers who are spending months of their own time — living like the soldiers and documenting those conditions. They’re not getting paid every day, but eventually they will get a story they think is important to be told.

How HEFAT Could Save a Life

RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues) is a program set up by Sebastian Junger specifically to train freelance journalists. Junger was compelled to start RISC after photographer Tim Hetherington died in Libya because journalists around Tim could have saved his life, but didn’t know how to administer basic first aid. These courses also help you develop the ability to understand what it’s like to operate in a war zone.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than 25 conflicts and worked in over 100 countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than 25 conflicts and worked in over 100 countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.