Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 4 — Investigating Political Messaging and Disinformation

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN’s Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 1 — New Election Digging Tools

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 2 — Preparing for Elections

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 3 – Investigating Candidates

Chapter Guide Resource

Webinar: How to Investigate Elections

Chapter Guide Resource

Video: GIJC23 – Investigating Elections

Social media platforms have grown into powerful domains of political messaging in elections. Their impact runs from the positive, such as boosting young and disenfranchised voter engagement, to the frivolous, like passing around candidate memes, to the gritty, exemplified by often misleading paid advertisements and coordinated disinformation campaigns.

Meanwhile, state-run media and partisan actors continue to be the primary amplifiers for autocrats. In places like Africa and India, these elements have manufactured false narratives via complex and disciplined messaging networks. Meanwhile, the growing monopolization of privately-owned TV channels by allies of authoritarian leaders drowns out opposition voices in countries like Serbia and Poland.

Thanks to data sharing and tracking, online campaign advertising now can be precisely micro-targeted to demographic subgroups. According to global fact-checking nonprofit First Draft News, this “patchwork of laws and a laissez-faire approach to political advertising have resulted in a lack of accountability in political campaigns, and the spread of falsehoods, mis- and disinformation.”

As a result, it is increasingly left to the press to cut through this noise and present evidence to voters about what is really going on.

While fact checking organizations generally do an admirable job of exposing online falsehoods and identifying manipulated images, often the role of tracking the individuals behind election disinformation or dirty tricks is left to investigative journalists. They’ve become the primary source for uncovering critical questions about election messaging, like: Who is driving the political messaging online? What conversations do they trigger among which voters? Where does the funding for the candidates come from?

For reporters in established democracies under siege from disinformation and anti-democratic forces, Sarah Blaskey, an investigative reporter with the Miami Herald, offers this insightful suggestion: Democracies are much more fragile than you think, so cover your election as if you are a foreign correspondent.

In this chapter, we share useful techniques for tracking political conversations, campaign advertisements, and disinformation narratives online, as well as tips for finding the sources of these campaigns based on interviews with some of the world’s leading media manipulation experts. We also share a list of “dirty tricks” that journalists need to watch out for, and explain how to reveal the culprits or questionable laws behind them.

A quick note on terms: This chapter uses the terms misinformation, which is broadly defined as false information that is spread regardless of whether there is intent to mislead, and disinformation, which refers to the publishing of deliberately misleading or biased information, manipulated narratives or facts, and propaganda.

Messaging Trends to Watch

First Draft News has flagged three main tracks for election interference.

- Disinformation intended to discredit candidates and parties.

- Information operations intended to disrupt the voting process and discourage participation, like misleading voters about the times and places to vote.

- Falsehoods designed to undermine public confidence in the results.

Claire Wardle, co-founder of First Draft News, warns that the “weaponization of context” – in which genuine content is willfully distorted – is the most persuasive form of disinformation in elections.

In addition to targeted falsehoods, countries worldwide are seeing countless examples of a powerful messaging tactic once described by right-wing media personality Steve Bannon — who briefly worked in the White House as an advisor to then-US President Donald Trump — as “flooding the zone with shit.” The goal here is to erode the public’s trust in media and other institutions by overwhelming people with a barrage of claims and conspiracies. Pushed by partisan supporters and amplified by social media algorithms that prioritize angry speech over facts, this kind of “naked assertion” messaging, which makes no effort to provide even the thinnest of evidence, represents a fundamental threat to democracy everywhere, according to a recent book analyzing the erosion of public trust in the US. Its authors – Nancy Rosenblum of Harvard and Russell Muirhead of Dartmouth universities– call the phenomenon “conspiracy theory without the theory,” and warn that “the new conspiracism imposes its own reality through repetition.”

Branko Čečen, director of the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS) – a GIJN member organization – recently warned that alarmingly large numbers voters in the Balkans region had fallen under the thrall of completely groundless online conspiracy theories. “It is unbelievable how large a percentage of people here are completely convinced by the worst possible conspiracy theories,” he says. While many of those who have been deceived are hyper-engaged in politics, Čečen noted that the deluge of false claims has also had an opposite, apathy-inducing effect on other citizens, who have “just retreated.”

Political campaigns are also increasingly using new technologies to get around rules to protect voters from phone harassment and intimidation, and can use anonymous mass text campaigns to urge supporters to swarm targeted events or voting stations. For instance, the US Federal Communications Commission bans the use of “autodialing” to text political messages to citizens. In response – rather than hire armies of volunteers to manually dial all the numbers – some campaigns are using semi-automated, peer-to-peer partisan texting platforms to bombard people with unsolicited mass messages.

Similarly, Indian President Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has built a massive army of volunteers who are primed to repeatedly share pre-written campaign messages and themes with their friends and family. And a 2021 analysis by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found rampant disinformation election campaigns across numerous countries on that continent. “The coordinated disinformation we have uncovered is just the tip of the iceberg,” explained Tessa Knight, a South Africa-based researcher with The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab). “It is expanding as governments and political figures learn to manipulate social media algorithms through fake, duplicated, and coordinated content production.”

Monitoring Political Messaging

Given the information deluge involved with elections, experts in the field try to organize and automate their monitoring as much as possible. They recommend following Facebook groups and Twitter lists, as well as using Google search tricks like site:twitter.com/*/lists “LISTNAME” to track targets, and paying attention to which related accounts and video channels social media platforms automatically recommend.

“When following people driving the conversation, the important thing is to let algorithms do the work — so when you follow one account, Instagram will automatically recommend a handle of others related,” says Jane Lytvynenko, a research fellow at Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center who studies digital media manipulation.

Find where the political conversations are happening. Every country, region, and ideological group has its preferred social media and messaging platforms – WhatsApp dominates in southern Africa and many parts of Latin America; in China, it’s WeChat; among right-wing groups, it’s largely Telegram; and in the Philippines, it is almost entirely Facebook. So, it’s crucial to identify the key platforms and messaging apps in your election landscape at the outset.

“The first thing that’s really important is to understand where conversations are happening, and the trends,” says Lytvynenko. “For instance, we see a huge uptake of Telegram in countries like Brazil, but it’s dwindling in the US. But be aware that Facebook groups continue to be a huge vector for mis- and disinformation.”

Discover what voters are trying to find out. Use the filters within the Google Trends tool to learn what voting communities are searching for, as well as sudden accelerations of interest in an election topic.

Find election-related tweets that politicians have taken down. Search for deleted tweets by politicians on the free Politwoops tool, which now features a database of deleted messages from elected officials in more than 50 countries.

Pay attention to the Telegram messaging platform. “Telegram is more politically relevant in more countries than a few years ago,” explains Lytvynenko. “As the bigger platforms like Facebook and Twitter have tried to be more aware of extremist movements, many of those groups increasingly feel safer on Telegram, and fear being shut down a lot less. Reporters should really watch these channels closely.”

Use this 3-step process for Telegram searches. Lytvynenko suggests this strategy for mining election threads on Telegram:

- Use the following operator in Google – site:t.me (keywords) – to find the few Telegram channels that might be useful to you, using keywords for the wildcard.

- Then open the tgstat tool, and plug in the interesting channels you find. “Tgstat is particularly useful because it gives you a view of the ecosystem, and then you follow those channels,” says Lytvynenko. Reporters can also use the Telegago tool for these searches.

- Finally, download the Telegram desktop app directly from the site. Doing so, Lytvynenko notes, gives you the option to export the conversation history. “That helps with any kind of bulk analysis. The beauty of the Telegram desktop app is that once you’re subscribed to enough channels, you can just use it as a search engine.” She says you can also find Telegram conversations that took place before you joined the platform.

Try Snap Map and TweetDeck for breaking news. SnapChat’s Snap Map feature shows heatmaps of messaging activity, and allows you to zoom in to a spot on a map, and watch the video snaps being taken there in real time. “It’s a useful tool, and it allows you to collect more context in a breaking news situation,” says ProPublica’s media manipulation expert Craig Silverman. TweetDeck allows you to channel social media posts from a particular place, or on a particular topic, into dashboard columns, and much more.

Try the copy-paste trick to check for allied partisan sites. Copy a chunk of text from the “About” or “Home” page of hyper-partisan websites, paste it into Google, and, within seconds, you can quickly see if it’s replicated on other sites. Also, look out for similar logos and layouts, as these could indicate the involvement of the same web designer.

Use Twitonomy to analyze hyper-partisan accounts. The Twitonomy tool allows reporters to dig into a particular Twitter account of interest, showing when and how often the person tweets, who they retweet, and what other accounts they reply to.

Try Mozilla’s new analysis tool tracking internet shutdowns. In March, Mozilla opened access to a vast dataset on internet outages around the world, some of which can be shown to be election-related. Apply for free access to the dataset through this form.

Tools to Dig Into the Sources of Online Political Ads

Online political ad campaigns increasingly use micro-targeting tactics, in which different ads, or slightly tweaked versions of the same one, target specific demographic subgroups. For instance, an analysis of the 2019 UK general election by First Draft News found that a Conservative Party ad stating “Get Brexit Done!” exclusively reached male users under 34 years old. But a near-exact copy of that the same advertisement, with just a new subtitle focused on health services and safety, was only seen by women. The report explains that social media algorithms amplify messages to groups that initially respond the most, eventually creating a reliable outreach strategy. And online ads can be a bargain for campaigns. First Draft News found one SnapChat ad that attracted more than half a million impressions only cost $765 to run.

Search Facebook’s Ad Library for political ads. Despite broad skepticism about data strategies at Facebook, several experts, including Julia Brothers, elections program manager at the US National Democratic Institute, say the Facebook Ad Library has grown into an important global tool for digging into political ads and the groups behind them.

“It should be a standard practice in elections now for reporters to be scanning the Facebook Ad Library, to see what political ads are out there,” agrees ProPublica’s Silverman. “You can target specific pages; you can do keyword searches. I suspect Facebook puts less effort into smaller countries, but if people want to run political ads on Facebook, they are supposed to register ahead of time, and get approved by Facebook, and those ads should be archived for years.” Silverman says reporters can dig deeper by searching names of interest they find in the Ad Library in the OpenCorporates database.

Check Google’s fast-growing political ads tool. While currently limited to select countries, Google’s Political Advertising Transparency Report is expected to grow rapidly in 2022 and 2023. It claims to include detailed information on the spending patterns of “verified advertisers” on election-related ads, and data is updated daily.

“It’s not as great as Facebook’s tracker, but you can download the data from Google – you can also visualize some of it – and you can do a little bit of searching, so I’d definitely check it,” Silverman says. Reporters in the US can also explore the excellent NYU Ad Observatory – developed by New York University’s Cybersecurity for Democracy Unit – for deeper insights into the organizations behind Facebook advertising.

Find local researchers already studying political ads. “Are there academics in your country who study political advertising? There usually are such people in almost any country,” Silverman says. “Definitely talk to them, and see what studies and data they’re collecting, which could be different from what the platforms are putting out.”

How to Track Actors Behind Election Disinformation

“Spreading false information, particularly on social media, is increasingly politically and financially profitable,” notes Lytvynenko. “One way to think about this as an investigative reporter is to ask: ‘Who benefits?’ If you’re worried about state-sponsored interference, ask whether the known disinformer states – Russia, China, Iran – benefit diplomatically from interfering in a local election narrative.” She adds: “Domestically, we see politicians using misinformation to bolster their own agendas; to make it seem that they have more support than they actually do; or to push through a particular policy.”

Given the shortened attention spans that social media helps generate, Lytvynenko says visual forms of disinformation are increasingly powerful – and recommends this comprehensive Washington Post guide for understanding the threat.

Who are the disinformers in elections? These can be political operatives behind coordinated domestic campaigns; hyper-partisan news media; foreign, state-backed troll farms; anti-democratic or political extremists; special interest groups; dedicated social media propaganda networks; and sometimes teenagers who have found a way to monetize political falsehoods, at a fraction-of-a-cent per site visit. They can also be unwitting participants. As First Draft News points out, a sincere assertion by a well-meaning citizen on a narrow issue can be repurposed by disinformation agents for use in election messaging. Their report offered this example: “A [person] misreporting the cause of an Australian bushfire season as an arson wave, which is then picked up by conspiracy theorists with a climate denial agenda.”

In 2016, an investigation by Silverman revealed that more than 100 pro-Trump disinformation websites were being run by young propagandists in a single town in Macedonia, some of whom earned up to $5,000 per month in traffic-based advertising revenue. Most didn’t care about the ideological differences between frontrunners Donald Trump and his Democratic challenger, Hillary Clinton. They simply found social media shares by Trump supporters to be more profitable – and yet their false and misleading posts are believed to have had a malign influence on the 2016 elections in the US. In 2020, French reporter Alexandre Capron found that a damaging disinformation campaign in the Democratic Republic of Congo was prompted by neither money nor political influence, but simply social media bragging rights.

“The first stage of misinformation we usually see is an absolute barrage of content on social media – usually visual content; sometimes out of context, sometimes clipped in a misleading way,” notes Lytvynenko.

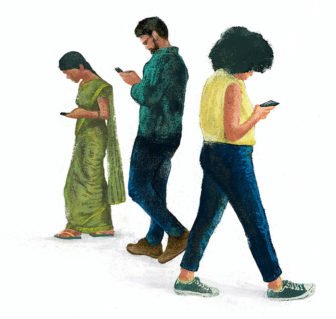

Try new disinformation insight tools. CrowdTangle has long been the go-to tool for tracking narratives on Facebook, Reddit, and Instagram. But Silverman warns this insightful tool is now constrained by new limits – such as the suspension of new accounts – and that it faces an uncertain future. This is, without a doubt, a blow to reporters in Facebook-dominated elections in countries like the Philippines. However, Silverman says emerging resources, like Junkipedia, have the potential to fulfill at least a similar digging function in most countries, and with more media-friendly features. Junkipedia focuses on viral misinformation and “problematic content.”

Use quick verification tools as new story leads. While fact-checking organizations typically assume the primary role in debunking, suspicious images and claims often crop up in larger investigations — which also require verification and can trigger valuable new leads. In GIJN’s popular image verification guide, journalism trainer Raymond Joseph meticulously describes how to use several user-friendly tools, including the free Photo Sherlock app and the Fake Image Detector app to check for manipulated photos in social media, as well as tips on how to spot clues in the images. Especially useful for time-pressed reporters on the campaign trail: He also explains how journalists can check photos in seconds on their mobile phones, by dropping photo URLs or web addresses into Google Images.

Educate audiences on the common types of election propaganda. Misinformation and disinformation are, unfortunately, now so widespread that it’s important to understand the different species of falsehoods – like agitprop, which is designed to provoke the audience into a specific action, or gaslighting, which spins false and deceptive narratives to attack established facts and undermine trust – and to contextualize their differences. For more on this, see this helpful explainer by the nonprofit group Data & Society, and this information disorder toolbox from First Draft News.

Track disinformation superspreaders. How can you distinguish between coordinated social media election disinformation and the innocent sharing of popular, but inaccurate, messages? CooRnet, a program developed at Italy’s University of Urbino, uses algorithms to identify suspicious sharing patterns. A tool within the R programming language, CooRnet packs even more power when combined with the Gephi open-source visualization platform.

Use the WeVerify Twitter SNA tool to find disinformation beneficiaries. In Chapter 1 of this guide, we profiled the new, free Twitter SNA tool which can be used to track, and graphically map, individuals behind election disinformation promoted on Twitter. Two reasons why experts regard this tool as a game-changer are that it focuses more on users than content, and that reporters need no special skills. Remarkably, this tool can also reveal the organizations and websites that potentially benefit most from deception campaigns.

Identify automated social media accounts. In addition to other useful insights, the accountanalysis app uses various techniques to expose suspected ‘bot’ accounts. For instance, its “Daily Rhythm” feature flags accounts that post tweets between 1:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. local time, when humans are typically asleep. Meanwhile, the Botometer tool offers scores on the likelihood that an account you’re investigating, or its followers, are bots.

Look for attempts to exploit falsehoods. Why do some politicians bother to push falsehoods that have already been debunked, and don’t appear to help their campaigns? “Once you tie disinformation to a certain politician or activist group, it’s important to see if they attempt to push any policies that would go hand in hand,” says Lytvynenko. “In the US, we see a huge restriction on voting rights off the back of the false ‘Stop the Steal’ campaign [which pushed the lie that Donald Trump was cheated out of victory in 2020]. That step will help you understand the purpose of the misinformation.”

Don’t forget the deepfake threat. Deepfake videos, which create realistic but fabricated images of actual people, can have a corrosive effect on public trust and democracy, as law professor Danielle Citron explained in a 2019 TED Talk. Similarly, Silverman has warned that “it is only a matter of time before the technology is used to impact an election.” His prediction has, so far, yet to come true, but experts have pointed to a growing trend in surprisingly effective and low-tech “cheapfake” tactics, like simply altering the caption on a political video. Silverman warns that elections are likely most vulnerable to deepfakes in the 48 hours prior to election days, as campaigns or journalists would have little time to vet or refute the videos.

Try InVid or the new Microsoft Video Authenticator to dig into suspected deepfakes, and use traditional sources to check whether the candidate was in the scene depicted in the clip.

Investigating Dirty Tricks in Elections

Election dirty tricks are often only pursued by investigative journalists for several reasons. Law enforcement agencies rarely address unethical tactics, voting oversight groups tend to take too long to react, media audiences are typically the targets or victims, and the actors behind one bad-faith campaign can often lead you to broader election scandals.

These are distinct from legitimate political tricks – like drowning media watchdogs in deliberately large data dumps. One classic example: the release of hundreds of pages of a candidate’s medical records close to a campaign deadline.

Rather, we’re talking about tactics designed to misinform or cheat voters, and they also include duly enacted laws that journalists can expose as anti-democratic, unethical, or racist. For instance, in 2014, a new law in the US state of Alabama mandated a narrow list of photo ID documents as acceptable proof to vote, including drivers’ licenses. But just a year later, partisan officials systematically closed the government offices that issue those licenses in neighborhoods likely to support the opposition party. To refute the claim that budget cuts were behind the moves, the Brennan Center, a nonpartisan law and policy organization, published a useful map showing how the 31 closures in the state happened overwhelmingly in counties with a high proportion of citizens likely to vote for the opposition.

The collaborative Comprova Project in Brazil has investigated elections claims for several years. Image: Screenshot

Use crowdsourcing to expose the truth. The origins of misleading election robocalls — automated calls that can deliver a massive amount of prerecorded messages — are notoriously difficult to track. But experts believe crowdsourcing is one of the best ways to detect campaign dirty tricks like these. In 2018, the Comprova Project successfully uncovered falsehoods undermining Brazil’s elections when a collaboration of 24 media organizations published the same WhatsApp number, and received a flood of tips for their combined audience. And the project continues to monitor possible campaign dirty tricks in the lead-up to that country’s 2022 elections.

“Crowdsourcing is hugely important, particularly when it comes to identifying early narratives for misinformation – and especially for WhatsApp,” says Lytvynenko. “Do a tipline, and collaborate.”

Warning signs to look out for include:

- Staged, targeted traffic jams on election days and voter registration days.

- Push-polling, where public opinion surveys use dishonest framing or manipulated messaging to purportedly show declining support for opposition candidates or policies.

- Disinformation robocalls to discourage voting, like spreading false information about the election calendar and ID requirements.

- Intimidating new voters by claiming voter registration will attract greater scrutiny by tax authorities.

- Anti-competitive practices, like starving an opponent’s campaign of skills or media opportunities.

- Deliberately confusing voters on mail-in ballot procedures.

- Using “dark PR” strategies to smear candidates with false or exaggerated links to unpopular individuals.

- Illegal or unethical use of public resources for campaign activity.

- Re-registering an opposition candidate’s home address in a new political district.

- Soliciting foreign interference.

Controversial legislative tactics could also include:

- Changing election rules to disadvantage, dissuade, or hinder opposition voters. These include laws designed to prevent voter registration on days popular with certain partisan communities, and laws that require the election identification that opposition voters are least likely to possess.

- Laws from the “autocrats’ election playbook.” See the list of legislative dirty tricks commonly used by authoritarians mentioned earlier in this guide.

- Extreme gerrymandering. Abuse of the process of redrawing political district boundaries can lead to elections in which voters don’t choose their leaders, but leaders choose their voters. As a result, parties that lose the popular vote by huge margins can still win control of representative bodies, making a mockery of democratic principles. While less of a problem in nations with proportional representation, like Israel and the Netherlands, or countries that allow non-partisan organizations to draw their legislative boundaries, like Australia and Canada, gerrymandering tactics remain a threat to voters’ rights in places like Hungary, the US, Hong Kong, Sudan, and the Philippines.

- Laws that use the pretext of voter fraud claims to make voting harder. Research indicates that in-person voter fraud is extraordinarily rare around the world and inconsequential to national results, yet many political parties grossly exaggerate this non-issue to introduce laws that intentionally make voting harder for certain groups that tend to vote against them. If your local data shows that in-person voter fraud is less common than, say, injuries from lightning strikes, or holes-in-one scored by golfers on their birthdays, then use visualization tools like Flourish to highlight these data anomalies. “Remember that most election fraud narratives start out locally,” Lytvynenko notes.

- Partisan polling station closures. Pulitzer-winning reporter David Cay Johnston says voter suppression by targeted polling station closures is on the increase in democracies. Look for databases similar to that of the Center for Public Integrity in the US, which can show targeted polling place shutdowns in areas of opposition support.

“Newsrooms need to ask audiences to be their eyes and ears in elections,” says Silverman. “So tell your readers or viewers: ‘If you see or hear attempts to deceive, or interfere with the vote, here’s how to reach us.’ After all – it’s their democracy.”

This is the final installment of GIJN’s serialized guide to investigating elections. The Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, and Chapter 3 have already been published.

Additional Resources

Investigating Politicians: Chapter 8 of the GIJN Citizen Investigations Guide

Essential Resources for the US Election: A Field Guide for Journalists on the Frontlines

GIJN Webinar — Digging into Election Disinformation in the US

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.