Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 1 — New Election Digging Tools

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN’s Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 1 — New Election Digging Tools

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 2 — Preparing for Elections

Chapter Guide Resource

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Chapter 3 – Investigating Candidates

Chapter Guide Resource

Webinar: How to Investigate Elections

Chapter Guide Resource

Video: GIJC23 – Investigating Elections

Since election rules, civic freedoms, and dominant information channels are different in each of the more than 150 countries that hold elections, there is no single investigative tool or technique that can be equally effective everywhere.

But there is a small group of established, all-purpose digging tools and methods that are remarkably effective for many, or even most, countries and election topics.

Here are two examples of highly versatile techniques:

- The “geocode” trick to track election violence. Having copied the coordinates of an incident from the “What’s here” tag on Google Maps, reporters can paste that string alongside the term “geocode:” in TweetDeck, plus a radius, to channel all social media posts and video from that area into a single column. The steps are set out in this explainer from Bellingcat.

- Boolean search. No matter their level of digital skills, leading investigative reporters around the world rely on the Boolean Google search method to laser-focus Google’s data-finding power – either with combinations of established search operators, or advanced Google “dorks.”

Using geocodes can help track or verify Twitter sources. Image: Screenshot

And here are two all-purpose tool examples:

- The Aleph database. Journalists have successfully dug into election-related crimes in different parts of the world with OCCRP’s Aleph document leaks database.

- Despite recent limitations – in which Facebook suspended the opening of new accounts – the CrowdTangle tool is widely used to track election disinformation campaigns on Facebook and Instagram.

Only a handful of new all-purpose tools for investigative journalists appear each year, and fewer still are ideally suited to election watchdogs. In this chapter, we profile two new versatile tools that experts say could immediately help in-depth election reporting in most countries. These experts, interviewed by GIJN, included Jane Lytvynenko – a leading investigator of political extremist groups, and a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center – and ProPublica’s media manipulation guru Craig Silverman.

The WeVerify Twitter SNA Tool: How to Map and Track Election Conversations

Once viewed as little more than a good video verification tool, the free InVid plugin has recently grown into a powerful, all-purpose social media tracking, digging, and data visualization tool. And it is especially well-suited for journalists investigating the influencers behind elections.

With funding from the European Union, and skills collaboration among several media organizations – including Agence France-Presse and Deutsche Welle – InVid’s WeVerify project has recently added a number of user-friendly features. These include a global fact-checking search feature; a plain-text file (CSV) feature for Facebook’s existing digging tool, CrowdTangle; and a “CheckGif” function that allows you to automatically contrast manipulated images with originals, side-by-side, so audiences can immediately understand the fakery.

But, for expert disinformation journalists, the potential game-changer is WeVerify’s new Twitter SNA tool.

“This was,” notes Lytvynenko, ”a very sweet tools overhaul at InVid.”

Silverman agrees: “It’s like a Swiss Army knife for journalists.”

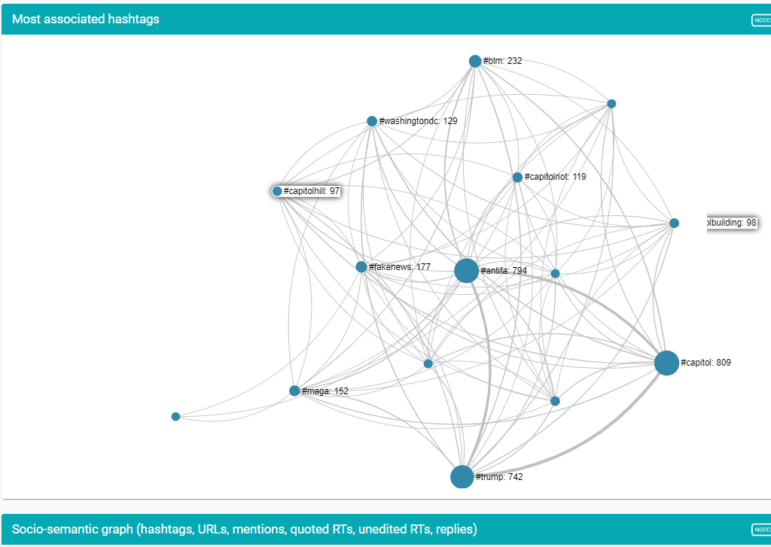

Just a small portion of clickable, graphical data on WeVerify Twitter SNA – this one, showing the largest influencers pushing an election conspiracy theory around the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol. Image: Screenshot

Tool Profile

WeVerify Twitter SNA can not only track – and graphically map – political conversations and deception campaigns on Twitter, but can also point to the individuals pushing the narrative, and, remarkably, also list the organizations and websites that potentially benefit most from these campaigns. It does this by listing the 25 sites most commonly shared by Twitter users who also used the disinformation terms being searched, and by generating detailed connections maps. (When GIJN mentioned this 25 most-shared-sites feature on a recent webinar with online intelligence experts in France, Cambodia, and Tunisia, they spontaneously reacted with comments like “Seriously?” and “No way!”).

You don’t need locations, coding skills, or even your own graphics to use this tool. You simply type search terms or hashtags into the search bar, and add a date range, and then an amazingly detailed, accessible stream of downloadable charts, clickable active users, and related website lists quickly flows down the page.

The system can fetch as many as 15,000 tweets at a time. In the rare cases where even more tweets would be involved – like particularly viral keywords, or general keyword combinations, like “Stop the Steal” – reporters can winnow down their searches by narrowing the date range.

How It Helps Election Investigations

Of particular interest for investigative journalists: the WeVerify Twitter SNA tool focuses on users and their connections, rather than the content – allowing quick insight into the influencers and beneficiaries behind political messages.

For example, when GIJN typed “love jihad” in the tool’s search bar – referring to a troubling Hindu nationalist conspiracy theory affecting elections and new laws in India – together with a recent two-week time frame, the tool fetched 4,300 individual tweets and the number of retweets and likes associated with them. The tool zeroed in on a handful of Twitter accounts who have grossly outsized roles in the campaign, either because they are popular influencers posting once or twice, or they are trolls, bots, or ideological extremists posting multiple messages per hour. Among the websites listed as top sharers for this campaign were companies selling merchandise to profit from the Islamophobic rhetoric. The first ‘top-tweeter’ we clicked on from the list of 25 most active accounts had posted chilling warnings against any opposition to Hindu nationalist policies.

Denis Teyssou, head of AFP’s MediaLab and founder of WeVerify, gave GIJN a demo on how reporters can use the Twitter SNA tool when investigating election conversations and disinformation campaigns. This demo revealed that the tool can show, among many other things:

- A bubblemap chart, in which reporters, at a glance, can identify the amplifiers of a disinformation narrative – with orange bubbles indicating people or bots that pushed a claim between five and 14 times in a day, and red bubbles showing those posting 15 times per day or more.

- A “propagation timeline” of election narratives, in a downloadable line plot – so reporters can link disinformation spikes to preceding news events. (Teyssou points out that you can easily shrink the timeline, and focus in on spikes, by adjusting the time bars on the graph).

- The 20 most retweeted users, potentially identifying celebrities or politicians endorsing an inflammatory claim.

- The 20 most active users, possibly indicating the trolls, influencers, or bots responsible for pumping the falsehood, and forcing it into top-trending lists.

- The 20 “most mentioned” people in tweets containing the disinformation keywords. Often these are populist leaders, or oft-memed public figures like, say, Bill Gates.

- Maps that visualize the connections between users and hashtags in a conversation around an election topic, with clickable bubbles scaled for their influence.

- An interactive heatmap, which Teyssou says can be used to identify possible automated bots. For example, if the account is posting a large amount of messages during the early hours of the morning at its supposed location.

- The 25 websites most often shared in posts that include your keywords, which allows reporters to simply click and explore those sites. Or they can also check a box next to the URL, click “submit Twitter SNA,” and the system will run the same full search for other Tweets mentioning that site. (When we searched for “antifa” and “fires” over the one-week period prior to the US 2020 election, the top shared sites list included Russian state media sites and ‘Blue Lives Matter’ sites – a right-wing countermovement to Black Lives Matter in the US.)

A Twitter SNA hashtags map from a search on the Antifa Capitol riot conspiracy, in which reporters can click on interactive nodes and follow the connections onward within the tool. Image: Screenshot

Getting Free Access to Twitter SNA, and Other Advanced Tools

To access the WeVerify Twitter SNA tool, reporters will need to apply and register for the group of advanced features on WeVerify (those easy steps below). Lytvynenko cautions that you’ll likely need to submit an email address linked to a news site or other research-oriented organization to be awarded a free, advanced tools account. (So avoid listing your personal Gmail or Protonmail account.)

But don’t let this process dissuade you. Application just takes a couple of minutes. Teyssou confirms that WeVerify simply wants to avoid giving access to bad-faith actors, since the Twitter SNA tool was designed for researchers, human rights groups, and investigative journalists.

For reporters less familiar with Chrome extension plugins, the process for activating and registering for the tool may seem confusing (as it was for this author!), so carefully follow these steps:

Open the plugin page at this link;

Click on the Add to Chrome icon;

Click on the jigsaw piece on the top right corner of the screen, and Pin the tool;

Click on the InVid icon that should appear in your toolbar, and click on ‘Login’;

Find the ‘Register’ icon at the bottom of the popup, and enter your professional journalists’ email address. (If you only have a personal address, click on the ‘Feedback’ message box and explain that you’re a journalist);

Retrieve the code sent to your email, enter it under the same Login icon – and you should then have full access to the Advanced Tools, including Twitter SNA. Start by clicking the “open toolbox” dropdown.

WeVerify Twitter SNA Tool Limitations

Lytvynenko warns that the feature will be less effective in countries where platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, or Telegram are dominant, and Twitter is little-used by voters. However, Lytvynenko stresses that the SNA tool still can be useful in these countries, because foreign actors involved with those elections – such as election observers, international media, and disinformers – likely will use Twitter, and their topic conversations can be tracked. Teyssou says it can also be used in combination with CrowdTangle, which can search Facebook, Reddit, and Instagram.

As previously mentioned, the Twitter SNA tool can fetch up to 15,000 tweets at a time, a potentially huge haystack in which to search for needles. So it’s smart to narrow your search terms or the date range on any viral election claims as much as possible.

Finally, while it’s easy to download the plot graphs and pie charts produced by the tool, there are no similar options for the associated hashtags graphic, so screenshots will have to suffice if you want to store or publish those charts

The UA/Pub Tool: Using the Greed of Bad Election Actors to Uncover their Networks

When a leading online sleuth like Craig Silverman says “If there’s just one thing I hope you remember from this presentation,” it’s worth sitting up and taking note.

That’s what ProPublica’s media manipulation expert said at a recent election reporting workshop hosted by the University of the Philippines, after describing what he called the “UA/Pub” tool for tracking otherwise-anonymous individuals behind election-related websites.

Silverman had already described about two-dozen exciting, time-saving tools at that point in his presentation, so why did he think this multi-step UA/Pub method was the most important for election watchdogs to know?

First because, despite the seemingly complex code you encounter, it actually requires no advanced skills at all. And second, because it takes advantage of the personal greed that motivates many election bad-faith actors.

There are many reasons why prominent figures in elections, whether campaign staff or special interest lobbyists or donors, don’t want the public to know that they are the true force behind certain individual websites. For instance, those sites could contain hate speech or disinformation, or illicit links to foreign powers.

Are they willing to sacrifice the “credit” for those websites to keep themselves hidden? Yes, and many can and do choose domain privacy settings to remove their names. But are they also willing to sacrifice the ad revenue that trickles in thanks to those sites? Probably not, Silverman reasons – which allows investigative reporters to track the people behind toxic, election-related websites.

How the UA/Pub Tool Works

- The people behind millions of websites have signed up for the free Google AdSense service, which then automatically populates their sites with ads. To receive revenue from those ads, the website owner needs to add a unique AdSense code string to their website source code – which always begins with “Pub-”.

- Likewise, millions of site owners have also signed up for the free Google Analytics service, which shows them the size and origin of their audience. To receive this data, they also need to add a simple, unique code to all the sites they control, which always begins with “UA-”.

- Site owners typically use the same ID tags, so Google knows to whom they should send both the money and data generated.

- Reporters can find either the identifying Pub or UA tags in any website source code (see those steps below), and paste them into any of three free tools – BuiltWith, SpyOnWeb, or DNSlytics – and quickly see all the other sites that also use those same revenue or data tags. This way, they can potentially find the networks and individuals behind mysterious election sites.

- Remarkably, the UA/Pub method also works with inactive or even long-dead websites. So reporters can potentially find how the same campaign actors profited from, say, opportunistic disinformation in prior election cycles, or were part of different domain networks. Silverman says reporters who have pre-installed the Wayback Machine Browser Extension can automatically get popup messages during their normal UA/Pub searches – alerting you to the fact that the tool has archived copies of former sites spat out in your investigation. You can then perform the same, simple UA/Pub search method on the archived pages, to search for the same tags. “Isn’t that an amazing, super-easy thing?” says Silverman. “It tells you right away, because you have the extension installed, and you can then do the same source code trick.”

“This is the most fundamental way I use to connect websites together,” Silverman concludes. “Even though it may seem technical, it’s really straightforward, and I really encourage reporters to practice this on sites you come across in elections.”

He says the AdSense “Pub” publisher ID, in particular, represents a strong indication that the same person or group is behind apparently unconnected sites. “The money earned from ads connected to the same publisher tag are all going to go into the same account,” he explains. “It’s very unlikely I’m going to put someone else’s Google publisher ID on my site, because they’ll earn all the money from my ad display.”

How to Find the UA/ Pub Tags for this Method

- Right-click on the white space of any webpage, and go to “view source code” or “view page source”.

- Don’t be intimidated by all the source code that appears! Simply use Control-F – or “Find” in the Edit menu – to search for either “UA-” or “Pub-” on the source code page.

- Copy the whole tag you may find – including UA or Pub and the numbers that follow.

- Open DNSlytics.com and paste the copied tag into the search bar. The search should return a clickable list of any other website domains that have used the same revenue or analytics tag. Note: this could include now-defunct sites that used the tag in the past.

- Repeat the same, brief process with the SpyOnWeb and BuiltWith tools because additional results often pop up, including inactive sites. Silverman says BuiltWith also works just with the URL from the website you’re investigating, but encourages journalists to manually search for the UA and Pub numbers as a means of verifying the unique connection between sites.

- Repeat the UA/Pub search on archived pages you find on the Wayback Machine.

- Confirm or expand your findings by dropping the URLs you come across into Whoisology.com and DomainBigData.com, and searching the available history for information gained in the UA/Pub search.

Note: If you know of a great new tool or database that can help reporters dig into elections, please share it with us at hello@gijn.org. This is the second installment of GIJN’s five-part guide to investigating elections around the world. The Introduction, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, and Chapter 4 have also been published.

Additional Resources

Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Introduction

Essential Resources for the US Election: A Field Guide for Journalists on the Frontlines

How Open Source Experts Identified the US Capitol Rioters

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.