Investigating the Amazon. Image: Heino Ollin for GIJN

Investigating Environmental Crimes: Tips From Reporters Covering the Amazon

Investigating environmental crime has never been more important as scientists from around the world stress the urgency of mitigating climate change.

Yet from small scale farmers to criminal groups and large corporations, there are forces that continue to destroy one of the most important ecosystems in the fight against climate change: the Amazon.

At the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Gothenburg, leading experts in investigating environmental crime shared their expertise and approaches. Among them were Joseph Poliszuk, co-founder of Armando.Info and part of a team that won a 2023 Global Shining Light Award, and freelance investigative journalist Fernanda Wenzel, whose latest investigation for The Intercept Brasil, “Ladrões de Floresta” (“Forest Thieves”), digs into land grabbing in the Brazilian Amazon.

Despite initiatives to protect the rainforest in Brazil, land grabbing and deforestation reached record levels after former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro came to power in 2019.

Wenzel decided to investigate and show, step by step, how people can grab land to then strip back the forest. “Forty per cent of deforestation, from 2013 to 2020, happened in undesignated public forests. And from 2019 to 2021, deforestation in these lands increased by 78% compared to the previous three years,” Wenzel said.

In the Brazilian Amazon, an area of public forest almost the size of Spain has not been assigned a specific tenure status by the federal or state governments: the so-called Undesignated Public Forests (UPF). These forests are not owned by Indigenous communities; they are not national parks; they are not private property. And they are up for grabs.

Wenzel’s methodology for calculating illegal land grabs was meticulous. She wanted to show that land-grabbers often have big industry behind them and to highlight the enormous financial stakes involved in these environmental crimes.

“It is the patrimony of the Brazilian people, but it is being sold for the profit of a few,” she said.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Expose Brazilian Land Grabbing

- Locating Land Grabs: Wenzel’s journey began with the MapBiomas Alert database. This platform collects deforestation alerts from various satellites and synthesizes the geospatial data into a QGIS shapefile. She looked for the largest deforestation alerts and found one for a huge area spanning close to 6,500 hectares. She decided this was the case she wanted to investigate.

- Finding the Culprits: Armed with the data from MapBiomas, she had the coordinates and the shape files she needed to search on Brazil’s Environmental Rural Certificate (CAR) database. The certificates registered here are not land titles, but still provide a digital “footprint” of land grabbing. In order to legally claim land, people have to go to the CAR website, stake out a polygon of proposed borders, and declare themselves as the owners. “Anyone can go into the system and say I am the owner of this land,” said Wenzel. “It is the landgrabber’s footprint. If cutting down the trees is the first step, filling up a CAR document is the second step,” she said, highlighting how there was a sad irony in the fact that the system had been set up to try and stop land grabbing but in many cases was now merely documenting it.

- Identifying the Perpetrators: Wenzel used the QGIS visualizer to match the information from the MapBiomas Alerts shapefiles with the CAR database. This allowed her to track down the people who filled out the CAR certificates for this particular deforested area. Once she had the names, she checked to see if these people and their relatives owned more land in the Amazon, which in this case, they did. She also wanted to check environmental fines and embargo databases to see if there were other people linked to this land. This painstaking research led her to discover the involvement of several family members in soy farming. “And big soy farmers in Brazil have big money,” Wenzel said.

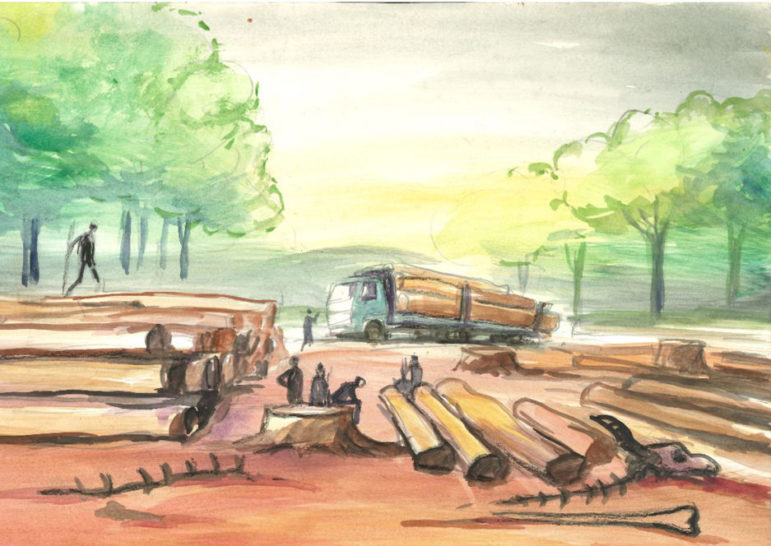

- Uncovering the Methods: To tell the detailed story of land grabbing in the Amazon through this example she unearthed a court case opened by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) against a group accused of land grabbing. The case detailed the use of chainsaws and tractors to clear the land. As Wenzel explained, this was crucial because using tractors for deforestation is significantly more expensive than other methods — hinting that greater resources are behind the deforestation. Wenzel used archived satellite imagery to monitor deforestation in the area in question. She realized that the land grabbers were doing selective logging: cutting the most valuable timber first and selling it to finance their logging operations. From the satellite images, she could see that an area larger than 9,000 football fields was being cut down. The estimated cost of logging such an area with tractors is about $2.5 million — but this is still only a fraction of the estimated $20 million that land like this could be worth once it is cleared and planted with products like soy.

- Preparing for Fieldwork: A vital part of any investigation is capturing the essence of a place, Wenzel noted, and understanding the local context is pivotal to providing a nuanced narrative. She highlighted how large numbers of the people working in the communities where these activities take place are impoverished. In her case, building trust through confidential interviews allowed access to sensitive information. She also spent a long time planning: “Don’t rush,” Wenzel warns. Safety measures in the field were paramount, including reliable local guides, constant contact with the base, and security and no-contact protocols. She suggested using satellite-based communication and tracking tools like Spot X and offline mapping apps like Avenza.

Using Satellites to Detect Illegal Mines

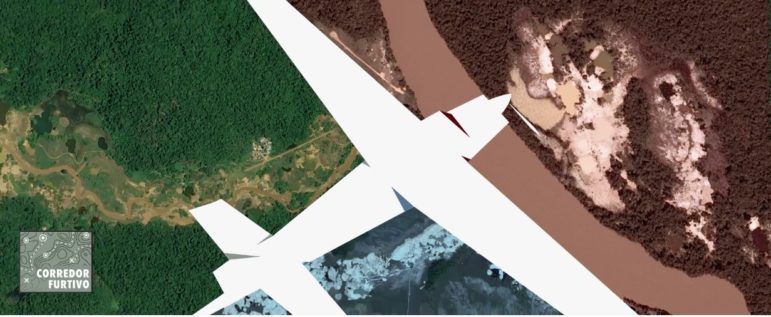

The Corredor Furtivo (Secret Corridors) project shed light on illegal mining in the Venezuelan Amazon. This region, though officially protected and home to Indigenous communities, faces destruction caused by organized crime groups engaging in illicit mining.

Amidst a crippling economic crisis in the country, a surge in illegal mining was suspected, but the true scale remained elusive due to the vastness and inaccessibility of the region.

“Almost half of Venezuela is rainforest, but only 6% of the population lives there,” Poliszuk explained.

To overcome the challenge of vast and inaccessible areas, Poliszuk’s team used satellite data to detect illegal airstrips in the region. In collaboration with Armando.info and Spain’s El País, supported by the Pulitzer Center, the project mapped more than 3,700 hidden mining sites and revealed how criminal groups have even built landing strips to transport their bounties out of the Amazon with planes.

The team utilized AI, databases, satellite tracking, and on-site surveys of remote jungle paths to create a compelling narrative enhanced with powerful visuals.

They trained an AI algorithm on Sentinel 2 satellite images to find airstrips, which appear as white marks on green terrain. The AI detected dozens of airstrips in the Amazon, but had some false alarms as well, so manual checks were needed. The investigation revealed not only the environmental devastation but also the involvement of Brazilian miners infiltrating Venezuela for illegal mining activities.

In-depth investigative reporting early on in the project helped the team navigate dangerous terrain, and helped in the planning of reporting expeditions, which led to further investigative stories.

“Thanks to our reporting on the ground, we realized some armed groups were using members of the Indigenous communities as slaves. There were huge cases of human violations,” said Poliszuk.