Insider Access to Chinese Vaccines: A Case Study in Pandemic Corruption from Peru

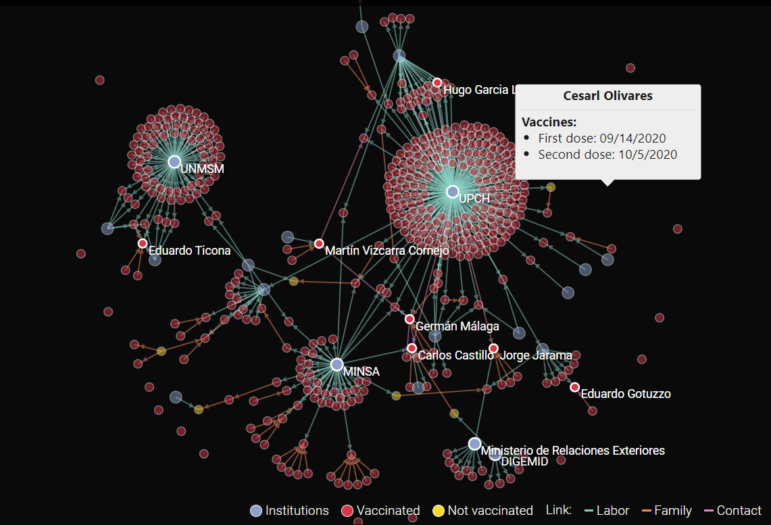

Peru’s Salud con Lupa outlet created an interactive graphic showing connections among the 487 influential individuals who received secret COVID-19 vaccinations in Peru’s Vacunagate scandal. Image: Courtesy of Salud con Lupa.

What could have a greater corrupting influence on leaders than money? The answer is hard-to-access medicines that could save their lives — and two newsrooms in South America uncovered its corruptive power in recent investigations into secret COVID-19 vaccine distribution.

Their reporting also suggests questions for newsrooms in other countries to ask: Did officials in their governments also accept secret inoculations before vaccination deals were struck? Did the fear of COVID-19 infections of their families cause normally ethical officials to expose themselves to a new form of corruption?

In Peru, several cabinet ministers and other officials resigned in February in the wake of the “Vacunagate” scandal, in which 487 influential people — including then-President Martín Vizcarra, leaders in academia, business executives, and family members of those elites — were secretly vaccinated while clinical trials were still underway, and months before any approved vaccines were available to the public.

In a series of more than 20 stories, reporters at GIJN-member Salud con Lupa (Health Under a Magnifying Glass,) an investigative newsroom in Peru, uncovered the details of what they call “vaccine diplomacy,” in which China’s state-owned firm Sinopharm sent 3,200 “courtesy doses” to Peru in parallel with the official doses for its phase-3 clinical trial there. Many of these extra doses were made available to people who would be involved with awarding contracts of any approved vaccine for the public.

The reporting team built a comprehensive database around those 487 individuals, and published an in-depth interactive platform that revealed the relationships between all the secret beneficiaries.

Salud con Lupa editor and founder Fabiola Torres — who also reported some of the stories — says the team’s reporting found that 40 influential people declined the offer of secret vaccinations, out of ethical or safety concerns. However, many more accepted. All recipients kept quiet about their clandestine inoculations, and some public officials told jarring lies to their as-yet unvaccinated public. Salud con Lupa reported that Peru’s Minister of Heath, Pilar Mazzetti, declared she would be “the last” in her sector to be vaccinated — even adding that “the captain is the last to leave the ship” — when, in fact, she had been secretly vaccinated weeks earlier.

“I think, with the pandemic, some powerful people panicked, and only thought ‘I need to be safe; I need my family to be safe — it doesn’t matter if it’s not ethical,’” says Torres. “This was a new way of corruption, because the most value was not money. It was vaccines, and to be sure they will be safe, and companies offered courtesy vaccines to help negotiate with the government.”

Torres also described her newsroom’s investigation in a Spanish language GIJN webinar.

She says the team is now investigating what they call “Vacunagate Part Two,” based on evidence that some secret beneficiaries have since jumped the line yet again — taking their third and even fourth inoculation doses, including vaccines from Western drug manufacturers.

How to Find Excess Doses

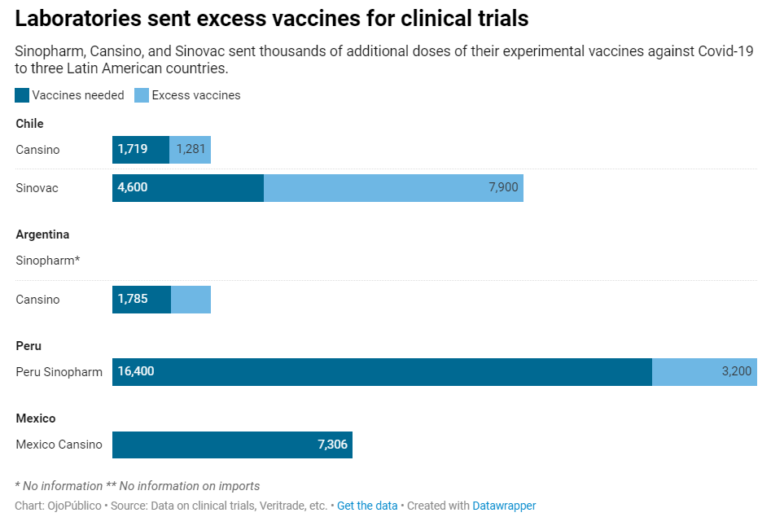

Investigative nonprofit outlet OjoPúblico — another GIJN member based in Peru — sought to find out whether secret, excess doses were also offered or sent to other countries in Latin America. Its investigation found that at least 13,500 excess doses were sent to Chile, Peru, and Argentina by three Chinese vaccine makers — in addition to the official 24,000 required for volunteers in vaccine trials in those countries. It also found that drug maker CanSino sent an as-yet unknown number of courtesy doses to Mexico.

OjoPúblico found that thousands of irregular excess vaccine doses were sent to three Latin American countries, and that an unknown excess number was sent to Mexico. Graphic: Courtesy of OjoPúblico

Noted OjoPúblico: “The offer of irregular vaccinations to public officials and celebrities occurred within the framework of the negotiations of the governments of Latin America with these pharmaceutical companies.”

Ernesto Cabral, an investigative journalist at the outlet, says the team realized it was important to show courtesy doses as a ratio of officially sanctioned clinical trial doses, so audiences could see the vast difference between normal excess vials and irregular vaccine diplomacy efforts.

So the team highlighted the fact that the 13,500 extra doses represented a whopping 55% addition to the research doses needed, compared to the small excess percentages typically seen in clinical trials.

“When companies send extra vaccines [beyond the clinical trial amount], it is normally two or three percent,” he explains. “But in Argentina, the excess was around 70% in the case of one company, and 171% in the case of Sinovac in Chile. What are they for? You cannot use those extras in any later regular vaccination program.”

Cabral detailed the steps OjoPúblico took to expose the practice, and added tips for reporters in other countries to consider. He says the team:

- First mapped the vaccine trials landscape by tracking the timelines for clinical trials and vaccine approvals for each Latin American country via the Covid19.trackvaccines.org tool.

- Dug into customs registries and public datasets on reported imports for each country. “For instance, Chile has a very good public dataset on imports; Peru also has a decent one,” notes Cabral.

- Used tools like Panjiva and ImportGenius to track physical shipments.

- Assigned key interviews to cross-border collaborators. In a deliberate strategy, Cabral — in Peru — called authorities in Chile; his colleague in Chile called authorities in Argentina; and their reporting partner in Argentina called authorities in Mexico. “I don’t know why, but what we found, at least in Latin America, is that, very often, public authorities are more willing to talk to foreign journalists,” says Cabral.

- Used social media platforms like LinkedIn to identify the leaders and principal investigators behind clinical trials.

- Used freedom of information (FOI) requests for executive registries and email strings on visits to presidents and ministers during the clinical trial period – and especially visits by Chinese embassy officials.

- Shared and organized dose data on Google Sheets, and used Signal when sharing sensitive information.

- Checked regulatory public disclosures by pharmaceutical records on the Edgar database, run by the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

In one story in its series, OjoPúblico found what Cabral calls “an important piece of the puzzle” following a public records request for emails relating to President Vizcarra’s visits, which were released after Peru’s Court of Transparency and Access to Public Information for the Presidential Office ordered them to be handed over. The emails revealed that Vizcarra held a vaccine-related meeting with Chinese diplomats between his two secret shots with vaccines made by a Chinese state-owned enterprise. They also revealed the secret vaccinations themselves — at 9:37am on October 2 and 2:34pm on October 29 — in sessions recorded as a “business meeting.”

Cabral suggests that reporters in other countries that were the site of vaccine trials also examine records of visits to heads of government and other executive decision makers — particularly by Chinese diplomats — during the period of those trials.

“Look in the visitors’ register to your executive authority to see if the person in charge of the clinical trial visited high authorities during the trials,” he says. “We found that it was a policy from Chinese pharmaceuticals to get these vaccines to our elites in order to have an advantage afterwards when negotiating the purchase of these vaccines. Probably something similar has happened in other countries around the world, and not only involving Chinese pharmaceuticals.”

A Conflict of Interest Cascade

As a public health platform, Torres says Salud con Lupa held an advantage in covering the Vacunagate scandal, as its reporters had an existing understanding of the trials, and had loyal health sources to turn to. However, she says it also faced a unique dilemma: many of those trusted sources, including doctors and university professors, were on the list of 487 secret vaccine recipients, and party to the scandal.

“It was very hard, because many of our sources were involved — relationships developed over time — and we had to be very sincere with our community, and say this is not good; this is not ethical behavior,” she says. “We even had to write a story about a way to rebuild our scientific community.”

Torres says that, during the pandemic, investigative reporters need to expand their focus for potential corruption beyond the usual drivers of greed or cover-up — and include the motivation of fear for family safety.

She says one troubling aspect of Peru’s vaccine distribution scandal was the early perception — even among some of the secret beneficiaries — that the deep conflicts of interest involved were normal and acceptable, or even sensible.

“Why did Salud publish more than 20 stories on this? — because we paid attention, and we saw that all these clear conflicts of interest were being normalized,” she says.

Torres says some officials genuinely believed they had done a good or even brave thing by accepting secret vaccinations before taking part in decisions on the public vaccination program, while Vizcarra claimed solidarity with brave trial volunteers who, unlike the president, did not know if they received a vaccine or a placebo.

Most striking in this regard was Salud con Lupa’s scoop on February 16, which revealed that the manager of a company contracted to monitor the Sinopharm trial secretly received a courtesy vaccine, and, one day later — “without any qualms” — joined the government’s committee to recommend pharmaceutical partners for Peru’s nascent vaccination program.

“We saw these things that were incredible, yet so many thought ‘this is normal,’” Torres says. “As journalists, we have to explicitly say, and explain, that courtesy doses are not normal; that this is wrong.”

Salud con Lupa also revealed that the fallout from the scandal itself caused 11,000 clinical trial volunteers to be “abandoned” — not informed, for an additional two months, on whether they had received a placebo or the real vaccine. “And many of these volunteers are people who work on the front lines — nurses and doctors — and they really needed to know what was in their bodies,” she notes.

Salud con Lupa produced a blitz of Vacunagate stories in the week after the scandal broke in mid-February, relying on human sources and clinical trial databases. Torres also asked health reporters in China about the marketing policies of certain drug companies there, and found that “it’s a usual strategy that they negotiate with courtesy doses to open the market in a country.”

She says the team then focused on finding the connections between the 487 secret beneficiaries in Peru. She says the team of five built a database that tracked the connections between those people, and layered the results in a visualization that connected each of the institutions, timelines, and individuals in the scandal.

“In health, it’s especially important to collect all the dots, and this we did with our database,” Torres says. “We tried to connect up the line of decisions. We identified the role each played. What we found, for instance, was that many of the family member beneficiaries were also connected to the health industry. We looked at where people worked before, and you can see many revolving doors and conflicts of interest.”

Above all, she says the series was founded on beat reporting sources developed over years, and journalists paying close attention to every public remark and listed name in the saga.

“We could do this in two or three weeks because it was like a bomb explosion in your neighborhood,” says Torres. “ We knew everybody.”

Additional Resources

How to Investigate COVID-19 Vaccine Contracts

How to Tackle the Global Undercount in COVID-19 Deaths: Reporters Offer Tips and Techniques

6 Tools and 6 Techniques Reporters Can Use to Unmask the Actors behind COVID-19 Disinformation

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.