How to Expose Lies from the Skies Using Satellites and Drones

Perhaps the most brilliant investigative technique developed this year was the use of censorship itself to expose China’s secret network of Uighur detention centers.

Months after receiving the Pulitzer Prize — along with two colleagues at BuzzFeed News — for her exposé of the places where roughly one million Muslims have been reportedly incarcerated for their faith, British architect Alison Killing told attendees at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21) how censored, blank digital tiles on government-controlled satellite imaging platforms can be used to reveal secret facilities.

Just one of the many reasons Killing gave for why the investigation needed to rely on geospatial analysis was this: “Because any source you speak to could potentially be sent to one of these camps.”

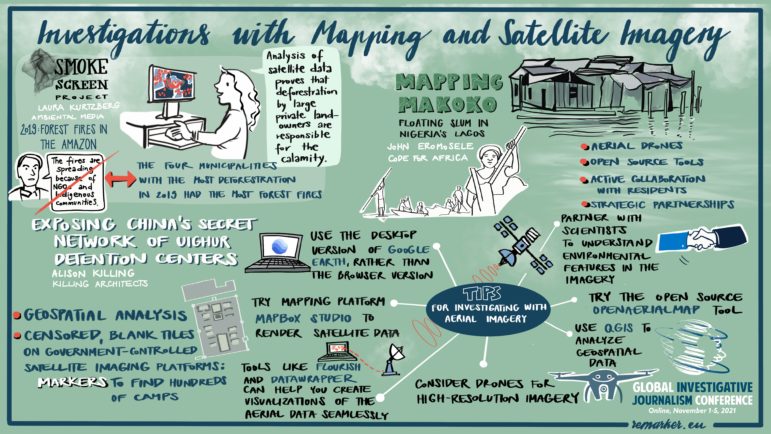

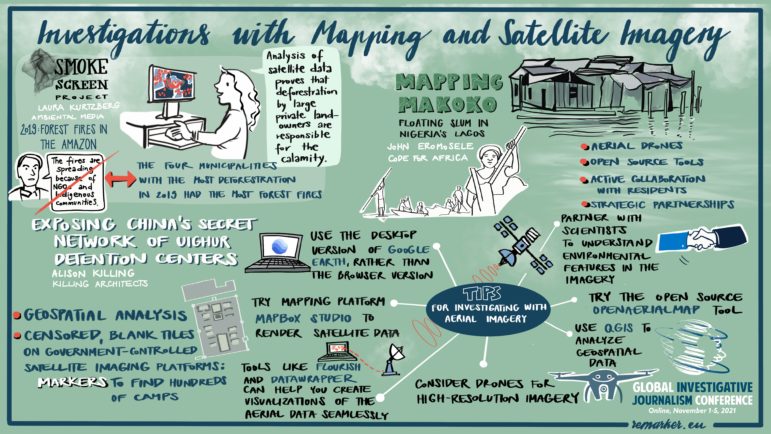

Yet this was just one of several innovative approaches to analyzing satellite and drone images described in the session “Investigations with Mapping & Satellite Imagery,” in which three speakers explained how open source tools can be used to expose lies from the skies. (See GIJN’s guide on satellite imaging resources here.)

If China’s Uighur detainees were hidden, the residents of Nigeria’s Makoko slum were invisible to policy-makers, with their entire community, built on a lagoon near Lagos, simply not featured on any official map.

John Eromosele, a project manager for the nonprofit open data organization Code for Africa, said aerial drones, open source tools, and active collaboration with residents were the key ingredients for surfacing this community near Lagos, whose invisibility had denied it services such as formal electricity, piped water, or even street names.

“We didn’t just bring the technical know-how for the Mapping Mokoko project; we taught individuals in the community how to do it. It was the locals who were flying the drones; who were doing the mapping,” said Eromosele. “We engaged a local educational NGO for community buy-in, because any community-based data project has to be people-centric. We deployed drones and a ground team with a customized data toolkit.”

Of course, some governments still lie about or try to cover up abuses that are so large that they cannot be hidden, such as the gigantic smoke plumes from the fires that, increasingly, have done catastrophic damage to Brazil’s Amazon forest. In 2020, Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, first denied the scale of the fires and then blamed both NGOs and Indigenous communities for their spread.

Laura Kurtzberg deployed satellite data to show massive deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Image: Courtesy of Laura Kurtzberg

At the GIJC21 session, Laura Kurtzberg, data visualization lead for Ambiental Media, a science-based journalism outlet, explained how the collaborative Smoke Screen project used careful analysis of satellite data to prove that, in fact, deforestation by large private landowners in the Amazon was responsible for the calamity.

“We found that the four municipalities with the most deforestation in 2019 also had the most forest fires, and 72% of forest fires were on medium to large private properties,” said Kurtzberg. “And the pattern continued in 2020.”

Killing and her colleagues used the censored tiles they found for known Muslim detention centers on China’s Baidu Total View platform as markers to find hundreds of other, secret camps.

“By mapping these censored locations, and then looking at these same locations with other satellite imagery, such as Google Earth, we managed to uncover what we believe is very close to being the full network of camps across China,” she said.

Killing also offered this striking tip: that reporters can find creative solutions to fill imaging blind spots. She revealed that where Google Earth lacked recent images for detention centers in southern Xinjiang province, the team found lower-resolution but up-to-date images of the area from the European Space Agency’s platform, Sentinelhub Playground.

Alison Killing discussed how she and her reporting team at BuzzFeed exposed Chinese detention centers using censored satellite imagery. Image: Courtesy of Alison Killing

They then compared building shapes from those images, where car-sized objects were shown as just single pixels, with patterns found on the higher-resolution Google Earth images to confirm detention camps in the Sentinelhub data.

And, where there were no open source options at all, Killing said the team approached the media team of a commercial satellite provider.

“We approached Planet Labs, who have a media program, and they very kindly gave us access to their high-resolution, up-to-date imagery for key locations,” she said.

GIJC21 Tips for Investigating with Aerial Imagery

- Use the desktop version of Google Earth, rather than the browser version, for complex satellite-based investigations where you need to track scenes over time.

- To help verify the identity of structures on satellite images, look for nearby objects people might need to use those structures. For instance, Killing revealed that makeshift car parking — on local roads, on nearby scrubland — turned out to be a good indicator of Chinese detention centers, as local security needs and the rapid pace of camp construction often did not include formal parking lots. Buses, guard towers, exercise pens, and, disturbingly, groups of people standing in formation, wearing dark red jumpsuits, were also useful indicators.

The BuzzFeed team used blank digital squares, like this one on Baidu Total View, as clues for where Uighur detention centers are located in China. Image: Courtesy of Alison Killing

-

- Use oblique satellite images to estimate the size of objects. The BuzzFeed team used these angles to count the floors in the detention blocks, which helped them establish a total capacity estimate of 1,014,000 detainees for the whole camp network.

- Try mapping platform Mapbox Studio to render satellite data. “Mapbox is free up to a point, but it’s a good thing for journalists to start with, as it gives a lot of interactive features,” said Kurtzberg. “RStudio is also very useful, and completely free.”

- Use QGIS to analyze geospatial data. Said Kurtzberg: “QGIS is the main tool I’d want to highlight — it’s completely open source, similar to ArcGIS, and is desktop software. I’d recommend this as a starting point for a lot of journalists, as not only can you do analysis with the tool, you can create maps and images for your stories, and work with Vector data and satellite imagery.”

- Apply for free access to advanced features in the Flourish visualization tool, such as Flourish Photo Slider to show before-and-after aerial photos. “Tools like Flourish and DataWrapper can help you create visualizations of the aerial data seamlessly and, I mean, within minutes,” said Eromosele. “It’s obviously important to control your costs, and, with a click, newsrooms can easily apply for free access to premium features.”

- Consider drones for high-resolution imagery, and seek regulatory guidance, skills, and cost savings through nonprofit providers like AfricanDRONE. “You can try to partner with AfricanDRONE for a subsidized rate,” said Eromosele. “We used a primary school field to do field tests for our drones, and got local government permission.”

- Partner with scientists to understand environmental features in the imagery. For instance, Ambiental Media partnered with Brazil’s National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters, and the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation for the Smoke Screen project.

- Try the open source OpenAerialMap tool to process satellite and drone imagery. “When you stitch all your drone images together — if you want to export it to Java OpenStreetMap — you need to send it to OpenAerialMap, which enables you to export it easily and edit,” said Eromosele.

Session moderator Marina Walker Guevara, the executive editor of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, said leading journalists in this growing investigative field, like the three speakers, “use satellite imagery, mapping, and other digital tools to defy censorship, expose wrongdoing, and make visible what powerful people and institutions want hidden out of sight.”