The passport of journalist Somaya Ali, who had to leave Yemen after she received multiple death threats and her house was bombarded by Houthis. Photo courtesy of ARIJ.

How They Did It: Reporting Online — and Offline — Threats to Yemeni Journalists and Activists

The passport of journalist Somaya Ali, who had to leave Yemen after she received multiple death threats and her house was bombarded by Houthis. Photo: Courtesy ARIJ

Yemen is a highly challenging place for journalists to work, given that they face threats from all sides in the ongoing civil war. In 2018, The Media Freedom Observatory in Yemen recorded 144 violations against media freedom in Yemen, including 12 cases of murder of media workers. There have also been numerous violations involving the wounding, kidnapping, harassment and assault of those working in media organizations.

Yemeni journalist Fuad Rajeh, who is based in Jordan, decided to expose threats to freedom of expression in his country by looking into the cases of two activists and two journalists who faced online and offline threats — one case ended up in murder — for speaking their minds on social media.

The breakdown of violations against media freedom in Yemen for the month of February 2019. Source: Studies and Economic Media Center

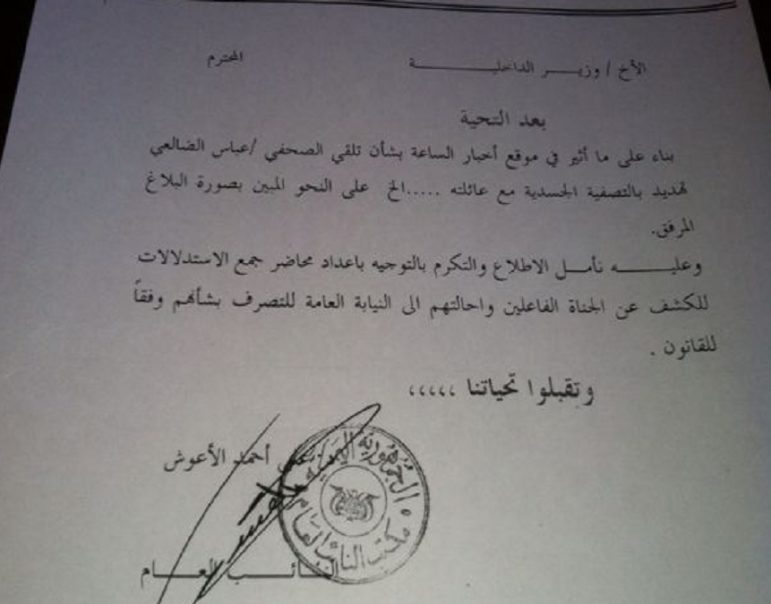

Case number one was Abbas Al-Dhali, who received numerous threats (and said his young son was nearly kidnapped several times) after he published a cartoon of Yemeni President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, in which he criticized the president for the fall of Amran province to the Houthis. Al-Dhali lived in Dhanar, but has since moved to Jordan. Raqeeb Organization, a Yemeni NGO which supports human rights, issued a statement condemning the death threats facing Abbas by the Houthis. The organization claims to have evidence linking these threats to the Shiite militia.

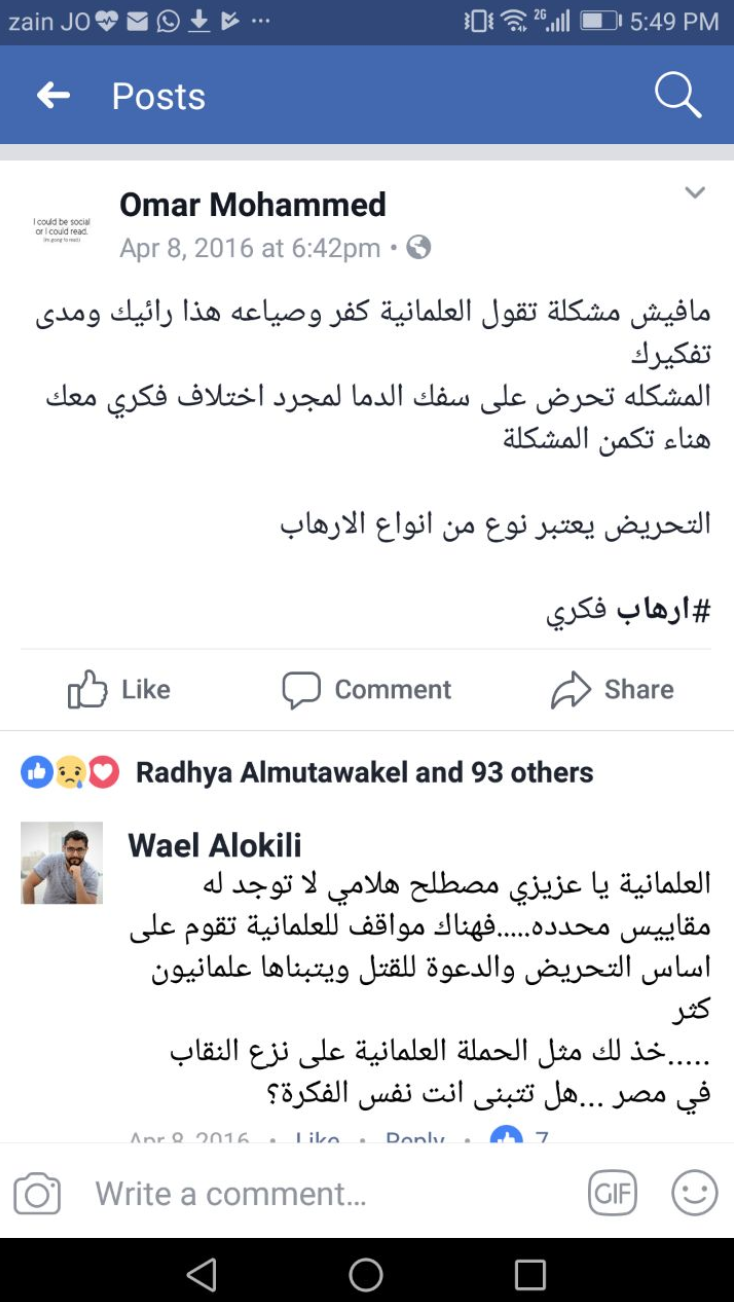

Case number two was Omar Bataweil from Adan, who was threatened and then murdered at the age of 17 because of his Facebook posts criticizing Salafists and jihadis.

Somaya Ali applied for asylum in Jordan after her house was bombed by Houthi forces. Photo: Courtesy ARIJ

Case number three was Somaya Ali, who wrote openly about war crimes committed by Houthis, as well as about civilians killed by the Yemeni government forces and looting by government supporters in Taiz province. She received death threats from government supporters, and has since moved to Jordan.

Four activists and journalists who faced death threats due to their online writings. Omar Bataweil (top right) was killed at the age of 17. Image: Courtesy ARIJ

Case number four was Abdul Qader Al-Junaid, who was jailed for 300 days by the Houthis due to his lengthy posts on social media in which he debunked Houthi claims. He was forced to flee from his home in Taiz province and now lives between Canada and Egypt.

Rajeh’s research into these cases spread out over five months, during which he conducted dozens of interviews. The resulting series of four feature articles were published on the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) platform.

Rajeh spoke with Amr Sayed, GIJN Arabic’s staff writer, about the biggest challenges facing investigative journalists in Yemen, as well as what it takes to protect himself and his sources from post-publication targeting. His answers have been edited for clarity.

What motivated you to investigate freedom of expression on digital platforms?

It was the idea of my colleague, Musab Shawabkeh, an editor with ARIJ, who supervised the investigation and participated in its preparation. But it was a subject that was on my mind, like all Yemeni journalists, due to the repression of activists and journalists in Yemen. Yemen, whether in areas under the control of the government and the Saudi-led coalition or in areas under the control of the Houthi militia, is near the bottom of the list of countries in terms of freedom of opinion and expression. Journalists and social media activists are exposed to all sorts of risks: arrest and torture; abduction and forced disappearance; threats; and prosecution. Some of them have received messages that their parents would not be safe as long as they did not stop [speaking out], and some of their homes were even bombed.

What research methodology did you use?

Yemeni journalist Fuad Rajeh. Photo: Courtesy of Fuad Rajeh

The plan was to identify cases of targeted activists and journalists as well as sources (officials or organizations) with whom we would conduct video and audio interviews; identify primary and secondary sources; create a time plan; find follow-up reports from organizations, trade unions and government institutions; and find statistics and all relevant data.

I started by interviewing sources who are now living in Jordan and collecting documents, including the official responses received by some of the activists when they reported threats to the Attorney General. We then recorded telephone interviews with sources in Yemen and outside Yemen, followed by interviews with the two governments in Yemen [the government recognized by the international community and the Houthi de facto government in Sana’a] and with some of the perpetrators of the harassment. Finally, we interviewed relevant Yemeni and international human rights organizations by telephone and via email.

We gathered a lot of information from social networks. What was interesting is how we used WhatsApp heavily, both to communicate with sources and to document threats. In fact, in one of the cases, in which an activist was assassinated, threats were sent to his phone through WhatsApp.

I worked with the help of local journalists in Yemen. International news networks tend to deploy veteran journalists in war zones, and most of the times they lack the local in-depth insights. This is why local reporters are crucial, not only to get information from trustworthy sources but also to get a better understanding of the context in which these events are unfolding.

What are the main tools for reporters to ensure their personal safety in areas of conflict?

Omar Bataweil was killed at the age of 17 after receiving multiple death threats. In his online writings, he had called for a secular state and religious reform. Image: ARIJ

Neutrality and professionalism, for both the journalist and the institution they work for; convincing all parties not to harm the journalist; [and proper] research and documentation. When documenting the murder of Omar Batuil, an activist in Aden, we did not resort to any method that could have caused trouble for the local journalists working with us but instead worked to communicate with our suspects in a formal manner and without any accusation. They may have refrained from answering our questions, but these suspects did not make threats or object or even prevent us from searching and inquiring.

However, on the ground, things may be different. The reporter may be harmed if he persists in following up those involved in areas where official authorities are completely absent.

Did you receive any threats during the investigation?

Al-Dhali said he was threatened by the president’s son after the publication of cartoons about the fall of Sanaa, in which President Hadi appeared vanquished by [Houthi leader] Abd al-Malik al-Houthi. Al-Dhali had previously met the son of President Hadi before the fall of Sana’a. “I recognized his voice right away and I could never mistake it,” he told me. Al-Dhali told us that he went to the Attorney General and filed a complaint against the president’s son, but the Attorney General told him to make the complaint against members of the president’s family, without [explicitly] calling out the son in the document.

Photocopy of the official complaint that Abbas Al-Dhali filed with the Attorney General’s office. Photo: ARIJ

When we asked Jalal Hadi to comment on Al-Dhali’s accusation, he failed to reply to WhatsApp messages or any other forms of communication. We believe he read the message, as it shows as “read” on WhatsApp. I got his number from reliable sources and called him from several different numbers, with no response. But I didn’t give up. I continued by calling three officials in the office of the presidency after confirming their relationships with Jalal. I sent them a copy of the letter I sent to Jalal, and I did not receive any response.

At the end of the investigation, and after trying to communicate with the president’s son, Jalal Hadi, I received a call from Saudi Arabia, where the president’s son lives. The caller was angry and was clearly trying to send me a message, but I did not give him the chance. Later, I learned that the caller was a friend of Jalal Hadi.

What are your tips for journalists interested in investigating cyber-bullying and threats?

I mainly try to focus on carrying out the interview in a way that will get me enough information from the interviewees. I can give you an example from when I met the Houthis’ Director of the Office of the Ministry of Human Rights. I asked him this question: “Mr. Talaat al-Sharjabi, activists and the families of activists say that they were arrested and possibly threatened or ill-treated in prison because of posts on social networking sites, which was documented by local and international human rights organizations. How true is this information?” During my questioning of the two government officials, which were directly involved in violations of freedom of expression, I did not directly accuse any of the parties but inquired as to what had happened and who was responsible.

Secondly, I advise monitoring social networking sites continuously. In the case of Al-Dhali, for example, he was well-known for his views, and threats were sent to him on a daily basis on his Facebook and Twitter accounts.

My third tip: Find primary documents. The investigation usually begins by tracing a few people, but as you dig further, you’ll find more information and more important details.

Finally, continue working on the subject even after the investigation is complete. Some of the people in our investigation continue to receive threats, perhaps even more serious and more severe than those we documented in the investigation.

Amr Hassan Sayed is GIJN Arabic’s staff writer. He currently serves as the Washington, DC reporter for Al Jazeera Mubasher (Live). He has previously worked for Al Jazeera in Qatar and in his native Egypt.

Amr Hassan Sayed is GIJN Arabic’s staff writer. He currently serves as the Washington, DC reporter for Al Jazeera Mubasher (Live). He has previously worked for Al Jazeera in Qatar and in his native Egypt.