Illustration: Roy Blumenthal for GIJN

Fighting a ‘Scourge of Secrecy’ and Uncovering Corruption in Malawi

Read this article in

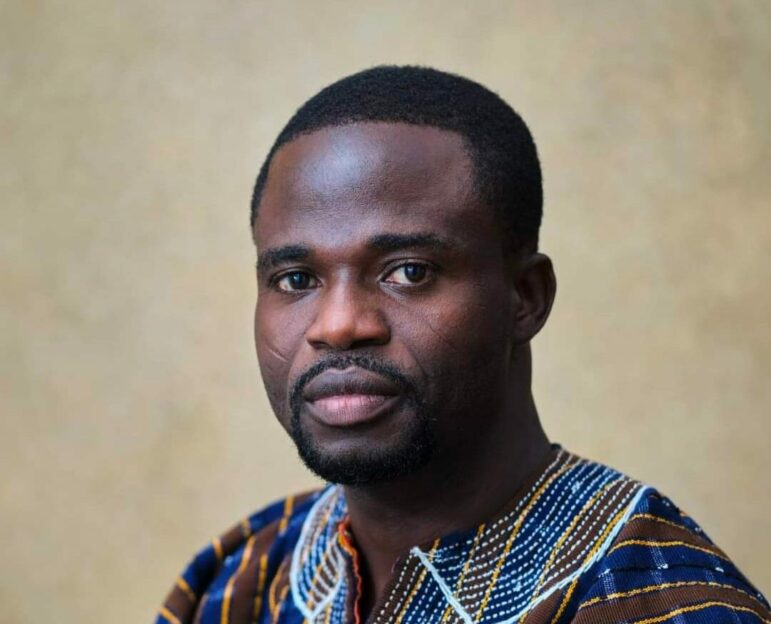

Malawian investigative journalist Golden Matonga wears many journalism hats. He serves as the director of investigations at the Platform for Investigative Journalism – Malawi (PIJ) and is currently the organization’s interim executive director, while its founder, Gregory Gondwe, is on a sabbatical as a John S. Knight fellow at Stanford University in the United States.

Matonga further doubles as the vice chairperson of the Media Institute for Southern Africa (MISA), a Namibia-headquartered nonprofit that promotes press freedom and the right to free expression, and as the chairperson of MISA’s Malawi Chapter.

A 2023 Hubert Humphrey fellow at Arizona State University in the US, Matonga is also a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), where he has participated in numerous high-impact stories, including the groundbreaking Pandora Papers and FinCEN Files investigations. In his home country, Matonga has been at the forefront of investigations into corruption and abuse of power.

Between May and June this year, Matonga traveled abroad to cover the US election for The Continent, a pan-African newspaper founded in 2020 and circulated to its audience mainly via WhatsApp. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Financial Times, and the Mail & Guardian.

In this interview, part of GIJN’s ongoing interview series with leading investigative journalists, Matonga shares his experience in collaborative investigations across Africa and beyond, along with some lessons he’s picked from a career spanning 17 years and tips he believes would improve investigative journalism in Africa.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

Golden Matonga: Well, it’s an intriguing question. You get to love all the investigations just like your children, really, but one of the major investigations that we have done as the Platform for Investigative Journalism is a [series] of investigations related to one business entity or one businessman. There are several elements around the story, and it’s important to us because it has been one investigation that is often a reference point for our work. I wouldn’t say it is my favorite investigation, but I think it’s one investigation which really defines the work that we have done in Malawi so far. (The UK businessman at the heart of the investigation was arrested in October 2021 by the UK’s National Crime Agency. Malawi’s Anti-Corruption Bureau subsequently discontinued bribery cases against the businessman’s alleged Malawian partners, but in August 2024, one of those decisions was challenged in court by a local anti-corruption group.)

Golden Matonga (center) accepting the 2022 MISA Malawi Award for Investigative Journalist of the Year, Electronic. Image: Screenshot, Facebook, US Embassy Lilongwe

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges you have faced as an investigative reporter in your country? And in your case, since you have also done collaborative investigations around the continent, what challenges have you seen that are pegging back investigative reporting on the continent?

GM: The biggest challenge in Malawi is still the scourge of secrecy, which journalists have to contend with whenever we are trying to deal with sources working in public offices. Even where the law has created an enabling framework for journalists to be able to access information, for example, in Malawi, there is an Access to Information Act, which is equivalent to the Freedom of Information [laws] in some of the Western countries, you still meet resistance from duty bearers to provide information, particularly when you’re doing investigative journalism. There’s a lot of resistance whenever people realize that they are talking to an investigative journalist who is looking for information, so that brings a lot of challenges.

In addition to this, we have seen that even in a country that has comparatively strong democratic values like Malawi, you still see investigative journalists being arrested. Our team has suffered from that fate. We have had one of our directors, [Gregory Gondwe], arrested, we have had physical threats on his life, he has had to jump to exile at one point because of threats on his life. So those are critical challenges that, as journalists, we still have to face.

In terms of the major stumbling blocks to investigative journalism in Africa at the moment, one of the critical aspects is the legal framework, the Cyber Security Act. Increasingly, in a number of African countries, there’s this law used to stifle investigative journalism, to stifle freedom of expression, and, generally, it also stifles people by increasing self-censorship, which means people who are supposed to be expressing themselves online are not able to express themselves the way they are supposed to because they are afraid of reprisals. That has a chilling effect on democracy, but also on investigative journalists because people who would be whistleblowers are afraid to come out. But also again, even those who have become whistleblowers, sometimes they can be arrested. We had a case in which the government wanted to force us, using the police, to divulge our whistleblowers who were the sources of our story. So, the Cyber Security Act has become one of the dangers to investigative journalism on the continent.

The Platform for Investigative Journalism – Malawi. Image: Screenshot, Platform for Investigative Journalism

GIJN: At the personal level, what was the greatest challenge that you faced during your time as an investigative journalist? How did you deal with it? And what lessons did you learn from that challenge?

GM: One of the biggest challenges that I have had to encounter as an investigative journalist is being able to publish, maybe at certain stages of my career, certain stories that the management of various newspapers that I worked for saw as a threat to the commercial interests of their newspapers. There have been challenges, again, in terms of the legal framework, obviously, where we have had to face threats of arrests in the past. Again, those were moments that could stop us from doing investigative journalism, but we have had to continue soldiering on by building coalitions, by creating platforms like PIJ, where there are no commercial interests, where we have the broader support of partners in the governance sector. So, that has been the experience in terms of the challenges and how to surmount them. I think the most critical aspect was to be able to build a coalition of allies both internally in Malawi to ensure that they support resources provided for investigative journalism work that we intended to do but also to build partners outside so that we could have the ability to even publish outside when stories were being suppressed back home.

One of the key allies, one of the key support structures for investigative journalism that has helped us to thrive in Malawi and me, personally, has been the IJ Hub, which is based in South Africa. They have been able to support us with resources to do the work, but also, crucially, whenever there were threats, they were able to come in handy and provide support. We have had support from the Media Institute of Southern Africa [MISA], which also has a chapter in Malawi and has also been very supportive of the work of journalists. I happen to be, currently, also part of the structures of MISA, so I’ve really been able to appreciate the role that they have played in terms of ensuring that when journalists are facing threats, they have someone to hold their hand. I think it’s very critical that we continue building these partnerships to ensure that investigative journalists feel safe and also have the right support to continue doing the critical role that they play in ensuring accountability.

Beyond the continent, we have had support from the Committee to Protect Journalists [CPJ]. Every time members of a media fraternity in Malawi were threatened, CPJ has come in handy to provide support to ensure that the journalists are safe. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has [also] done critical work supporting collaboration within the continent and beyond. The ICIJ model has ensured that African journalists can report on African affairs. Also, by helping them with critical technical support, we have been able to collaborate by drawing on each other’s strengths to ensure that there is good investigative journalism. So, both regionally and globally, ICIJ has played a very critical role, and centers like PIJ have benefited from doing investigative work with ICIJ.

Within the continent [Africa], I think one of the critical aspects that we need to review as journalists is how to collaborate regionally, but also continentally. I think there is more collaboration between African journalists and their colleagues in the West than among our regions, for example, West African journalists collaborating with Southern African journalists. So far, most of the [intra-African] collaborations that we have done have been under the umbrella of ICIJ; that’s when you see West African journalists collaborating with Southern African journalists. But I think that as a continent, we need to do more to ensure collaboration within our own ranks.

GIJN: You have done many interviews as a part of your investigative reporting. What is your best tip for interviewing?

GM: I think the critical aspect of a good interview is what you do before the interview starts, that is research. So, the most important tip is, make sure that you have done your research and you know the subject matter. A very good interview will always be the result of good research that happens before it.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

GM: I am fond of coworking, so any app that enhances coworking is my favorite — whether it is ICIJ’s iHub, whether it’s a Google doc that will help me co-edit a story with my colleagues, I am always excited to see how we can employ any collaborative tools that come up in our work because I believe in the power of collaboration.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten thus far in your career and what words of advice would you give to an aspiring investigative journalist?

GM: The best advice I’ve ever gotten in my career is to be patient with my work. I am one of those who are always eager to publish. But there is a lot that we miss when we are rushing, so to be able to calm down whenever you are doing an investigation is important. Being thorough ensures that you cover as much ground as possible and that you are protected legally. That ability to tamp down your excitement is very critical.

I would always encourage anyone who wants to be an investigative journalist to just start. Start and learn from the best, you will perfect the art along the way. There’s no one who comes out of nowhere and becomes a successful investigative journalist. But you keep on building your sources’ trust [and] you keep on publishing.

GIJN: Now, there must have been somebody who made you love investigative journalism. Who is that journalist that you admire, and why?

GM: For just journalism in general, I was a fan of one former BBC foreign correspondent from Malawi, the late Raphael Tenthani. He used to write a political column as well, and I was a huge fan of his column and his writing. But then, eventually, I got excited about investigative journalism because of Mabvuto Banda. He used to be a prolific investigative journalist in Malawi, and his work both in Malawi and internationally inspired me to try to achieve the same level of standards. He did some of the most consequential journalism in Malawi and it was that impact, that ability to hold the powerful to account, that really made me look at him highly and consider him someone who could possibly be a role model.

There are a number of African journalists again who are doing really good, exciting work that I am really proud of and look forward to reading. I’ve also enjoyed working with Simon Allison from The Continent. I will also mention my colleague Gregory Gondwe, one of the most courageous journalists we have at the moment. His work is always inspiring in terms of integrity and his sheer determination to persevere and push through stories regardless of the consequences. I think that that is something which really should be the spirit that many journalists should try to get.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made and what lessons did you learn from it?

GM: In my early days in journalism, I was always excited to write stories but I was not always as thorough in fact-checking my own stories. So, I’ve had embarrassing moments when I ended up maybe misnaming people in my stories. You need to be thorough, because working for a newspaper, a printed newspaper, you can’t go back and edit the names of people. It was a clear lesson on how we need as journalists to be very thorough in our work, and always make sure that we write and read and re-read the work before submitting it. It’s also very important that the gatekeeping process is very thorough, because if a journalist makes a mistake, then their editor or sub-editor should be able to pick it up.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

GM: Burnout is a serious challenge, but I think it’s something that most newsrooms [in Africa] do not invest enough in to help their teams avoid it. It’s not just about the physical aspect of exhaustion, but also the mental aspect as well. You get tired of chasing stories, fighting with sources for information, and sometimes reading feedback; the negativity that comes with some of the reporting can also lead to mental stress for journalists.

I am not sure where I have had to employ specific measures to help me avoid burnout. But I do try as much as possible, whenever I have a chance, to get away from my work, to focus on some things outside [journalism], and to have some other social activity.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism in Africa do you find frustrating and hope will change in the near future?

GM: When you expose abuse of office or corruption, you would expect that other aspects of a governance structure, like law enforcement, will pick up the matter and ensure that there is accountability for those whom you have exposed as an investigative journalist. But often, you report and there’s no follow-up action by law enforcement or even other stakeholders like civil society. So that becomes a really big problem for investigative journalism on the continent: that there is little effect beyond the reaction on social media, or your followers. So, I think that’s one aspect that has been very frustrating from an investigative journalism point of view.

Benon Herbert Oluka is a Ugandan multimedia journalist, a co-founder of The Watchdog, a center for investigative journalism in his home country, and a member of the African Investigative Publishing Collective. Oluka has served as a reporter and editor in The East African, Daily Monitor, and The Observer newspapers. He’s also had work stints at the Reuters news agency’s sub-Saharan Africa Bureau in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the BBC World Service’s Newsday program in London, United Kingdom. As a freelance writer, Oluka’s work has been published in The Africa Report, Africa Review, Mail & Guardian Africa, Mongabay, and ZAM magazine.

Benon Herbert Oluka is a Ugandan multimedia journalist, a co-founder of The Watchdog, a center for investigative journalism in his home country, and a member of the African Investigative Publishing Collective. Oluka has served as a reporter and editor in The East African, Daily Monitor, and The Observer newspapers. He’s also had work stints at the Reuters news agency’s sub-Saharan Africa Bureau in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the BBC World Service’s Newsday program in London, United Kingdom. As a freelance writer, Oluka’s work has been published in The Africa Report, Africa Review, Mail & Guardian Africa, Mongabay, and ZAM magazine.