Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano for GIJN

GIJN’s Guide to Undercover Reporting

Read this article in

This guide was written by GIJN’s Resource Center director Nikolia Apostolou and GIJN reporter Rowan Philp. Editing was by Reed Richardson and Laura Dixon. Illustrations are by Smaranda Tolosano.

Across the world undercover investigations have produced extraordinary, impactful journalism. In countries without public record transparency rules or strong source protection laws, going undercover can be one of the few tools reporters have to reveal public interest stories.

This GIJN guide provides advice from seasoned investigative journalists and showcases great case studies from around the world. But it also highlights mistakes reporters have made and the many ethical considerations that must be weighed before undertaking an undercover report.

Sections of this guide include:

Before any journalist commences any type of undercover or clandestine operation, it is imperative that they educate themselves on their country’s legal and cultural framework around recording without consent. In many parts of the world, reporters may face protracted legal action, government detention, and even physical danger for secretly filming or recording someone without their knowledge.

NYU professor Brooke Kroeger is author of “Undercover Reporting: The Truth About Deception.” Image: Screenshot

“This is expensive work, it ties up staff for months on end, it’s stressful, and it requires all kinds of legal vetting, so you really should think hard before undertaking something like this,” says New York University professor Brooke Kroeger, author of the book “Undercover Reporting: The Truth about Deception.” “But, historically, the impact of these stories, when they worked, was just extraordinary. And they are the stories we remember.”

Still, the risks related to undercover reporting are significant and can run the gamut from flawed reporting and debilitating lawsuits to a broader erosion of the public’s trust in the press. Peter Murimi, Kenyan director and producer at BBC Africa Eye, one of the continent’s top investigative units that often relies on undercover techniques, says safety is paramount when contemplating an undercover operation. “If you cannot do it and [keep] everybody safe — that’s something to block the process,” he explains. “You have to make sure once you’re done that your whistleblowers are safe and your contributors are safe. And the crew are safe.”

Practical Tips

Undercover reporting can be one of the most dangerous and difficult ways of collecting evidence. Journalists who embed themselves might not only be facing legal action, but even threats to their lives. That’s why many major news organizations like the BBC have established clear guidelines on how the editorial and reporting processes of undercover work should be carried out.

For more than 20 years, Indian journalist Aniruddha Bahal has been doing undercover investigations: first, at the magazine he co-founded, Tehelka, and, since 2005, with the nonprofit team at GIJN member Cobrapost, where he’s founder and editor-in-chief. Since the first undercover story on cricket players fixing matches in 2000, Bahal and his team have had great impact. A prime example of their undercover muckraking resulted in 11 Indian MPs resigning after they were allegedly filmed on camera receiving bribes to ask questions in parliament.

But way before the record button is pressed, Cobrapost’s investigative team examines the following issues: “Number one is that we always have to have prior information about the tendency of those people to commit illicit acts,” Bahal explains. “It’s never a fishing expedition. Number two if there are no documents to get the story… the only means is the hidden cameras.”

Central to the discussions for Bahal and his team is whether the story is of public interest. “(In 20 years) none of the subjects have ever said that our stories weren’t of public interest,” Bahal notes. But he cautions that the use of hidden cameras, when not deployed professionally, can end up sensationalizing stories, something that has frequently happened in India.

In the late 2000s, an undercover reporting boom took place and the roughly 600 TV news channels in that country began producing multiple stories with hidden cameras. Bahal believes that’s how undercover reporting got its bad name. “Shoddily crafted stories and some where the public interest could not be ascertained clearly began to cloud the field,” Bahal explains. “But right now the pendulum has swung the other way. There is hardly anybody using hidden cameras.”

BBC Africa Eye presses its reporters to think through the consequences before any undercover reporting is approved. “Can this story be told in any other way?” Murimi asks, when discussing how BBC Africa Eye explores a new story idea. “Undercover should be the last resort, it shouldn’t be your first to go to… What is the public interest? If the public interest isn’t there, then actually it’s not worth it.”

The team’s next step — as in any other investigation — is to collect prima facie evidence. Without it, the team could end up embarking on a story that comes across as a character assassination. “It has to be documented, very specific and very elaborate, that the person, or people, or institution you’re investigating actually is committing a wrongdoing which the public should know about and that should be exposed,” Murimi emphasizes.

Another critical task: examine whether everybody involved in the reporting team can be kept safe. If that’s not guaranteed, that may block the BBC’s pursuit of an undercover operation. Sometimes the group will bring in outsiders to assist in the reporting if they know the community well but don’t actually live there. This provides more long-term safety and security for those involved after the story is published.

Often overlooked, a communication plan is also needed to ensure the safety of those going undercover. How will the person filming be able to alert the nearby team if something goes wrong? Sometimes that can be done via phone, but the BBC has also used a simple, panic button device that immediately triggers another member of the team to end the ruse or disrupt the situation.

The final step before filming “is actually working on the narrative of the story,” Murimi explains. “How are you going to film it out, what are the scenes you need, in terms of investigation-wise what needs to happen, but also what needs to happen in terms of the filming.”

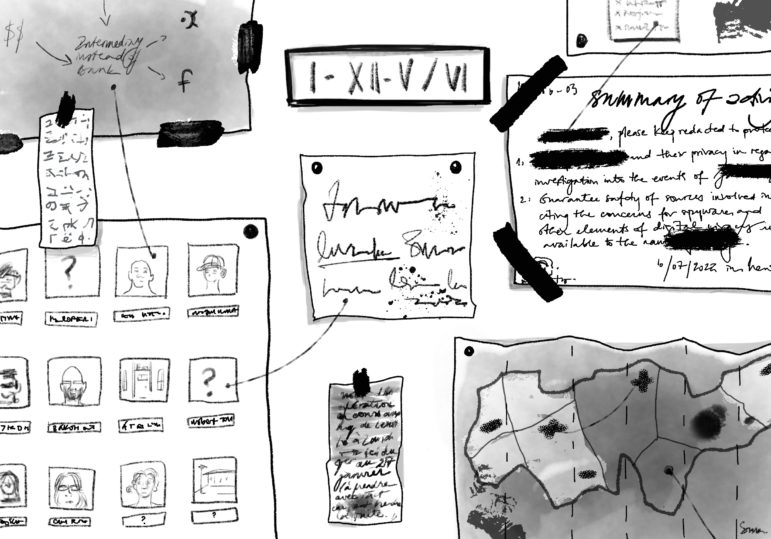

Before the undercover portion of any investigation begins, experts recommend a thorough examination of other evidence to understand the subjects involved and what, exactly, the clandestine reporting will provide for the story. Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano

Another female producer for BBC Africa Eye who travels the continent to train undercover operatives (and therefore wishes to remain anonymous) explains that undercover reporting “is less exotic than it appears to be, because 80% of it is traditional, thorough, source work, some intelligence work, and paperwork, and then the final 20% is what brings you the result. But if it’s not underpinned by this very solid base of traditional work, it’s just not going to work.”

The two BBC producers agree that secret filming works well when the burden of the allegations needs to be taken off the shoulders of the source and when it’s difficult to document wrongdoing, as in cases of sexual abuse or racism. This they did with BBC Africa Eye’s documentaries “Sex for Grades” and “Racism for Sale.”

Some of the most dangerous — and common — undercover stories involve investigating criminal activity. Nigerian journalist Tobore Ovuorie, who went undercover to expose trafficking of African women to Europe for Nigeria’s Premium Times, tells GIJN what journalists going undercover should think about and plan for:

Preparation

-

-

- Do thorough preliminary research, not only about what and who you’re investigating, but the process by which you will achieve your reporting goals. Some of these include: mapping out places you will go to, how you’ll get in (if access is restricted), with whom, when, and why.

- Don’t disclose to anyone other than the team you’re working with that you’re going undercover, not even your family, friends, or other colleagues.

- Safety measures in place must include an escape plan, a rescue team, enough money for emergencies, an effective means of communication with your editor, and tracking devices for extreme undercover scenarios, such as embedding yourself in human trafficking rings.

- Get good legal advice before you start the undercover operation. You might also need these lawyers to get you out of trouble. Have them on standby during the undercover portion of the reporting because there could be an emergency requiring their services. Depending on your relationship with these attorneys, you could get this legal help for free.

-

Undercover Operational Tips

-

-

- “After identifying the various groups/persons you need and mapping out your undercover journey, get into the ‘act’ with them,” Ovuorie says. “You must be very secretive, yet appear simple and friendly. Be ready to play along, but withhold vital details and observe the other party closely. You must never be predictable.”

- “Go with a secret recording device, but certainly not a pen or wristwatch because they are easily detectable by criminals. Make sure your device(s) is/are well charged and in top form,” she says.

- “Always trust your gut instincts and never get desperate to complete the story,” Ovuorie cautions. “Determine the extent you want to go and never expect all your plans to happen the way you penned them. There could be surprises around the corner.”

-

Polish journalist Patryk Szczepaniak wrote about his undercover reporting experience for GIJN in 2019. Image: Screenshot

After returning to the newsroom, Ovuorie advises colleagues to be alert to the impact the operation may have on a reporter, in particular potential mental health consequences. She advises the team to ensure someone regularly checks in on the person and has some knowledge of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Exposing wrongdoing inside the food industry is another common undercover story. Polish journalist Patryk Szczepaniak, who works for the investigative program Superwizjer at TVN Discovery Poland, previously wrote about his undercover reporting experience posing as a butcher.

Szczepaniak’s advice includes:

-

-

- “Setting the story. The best character is built on real events, emotions, and histories. Use memories and experiences from your own past to make your story authentic,” he says.

- “Lies… My advice is that it is better to say as little as possible. Memorize your story and be prepared to have it checked by anybody at any time,” Szczepaniak warns.

- “Digital footprints. Delete everything you can from the internet, including all social media. Profiles need to be deleted and, if necessary, replaced with new ones. Do it carefully and well before the assignment,” he advises. “Learn from my mistake: I left one of my old photos that appeared under my real name on the sixth page of a Google image search. It later led to my exposure where, during one of my night shifts at around 3 a.m., I was invited to my boss’s office ‘to sign a contract.’”

- “Change of appearance. Shaving, growing, or dying hair; cutting or growing a beard; growing or cutting a mustache — it is worth taking a closer look at your external appearance, as well as inside your wardrobe,” he says. “If the clothes don’t match your story, buy new ones, including socks and underwear.”

- “Change of personality. Adapt to your environment. If it is an academic environment, behave and speak like an academic. If it’s a slaughterhouse, behave and speak like a butcher. If it’s a criminal network, behave and speak like a criminal,” he emphasizes.

- “Research. Learn whatever you can about your assignment,” Szczepaniak says. “I watched plenty of documentaries about meat production and some pretty nasty videos on LiveLeak and YouTube regarding animal cruelty.”

- “Identification card. Faking an ID is a crime in Poland, so we decided not to do it during my assignment, and there wasn’t really a need for it,” he says.

- “Observe and document. These are basic ethical rules of undercover journalism. You’re there to document systems or criminal activities, not to provoke or to stage situations,” he notes.

-

Tools and Gear

Just a few decades ago, journalists had to find ways to hide huge cameras inside briefcases. As with regular cameras, the costs and size of recording equipment has dropped and you don’t have to spend thousands to go covert. Hidden cameras sell for as little as US$15 dollars and are now available in camera shops and other mainstream consumer websites.

“From 2005, (the gear) started getting miniaturized,” Cobrapost’s Bahal explains. “I don’t usually talk about what we use, but if you’re going with a body device, it opens yourself to being searched and, of course, (in the case of hidden) non-body devices, people might tell you to leave them out of the room. So you have to balance it and see who you are going to meet.”

The variety of hidden cameras is large; there’s the popular camera in a button shirt that has been around for decades. But now the cameras can be hidden nearly everywhere: in watch wristbands, car keys, USBs, glasses, or pens. If you need to leave the camera in a room and go, there are cameras hidden in alarm clocks, air-purifiers, DVD cases, air fresheners, lamps, exit signs, and of course teddy bears.

You also have to choose whether it’s a camera for indoor or outdoor use, whether it needs to be more mobile — and run off a battery or be plugged in — or be a fixed, hard-wired model.

When choosing which camera to use, make sure its resolution is at least 1080 pixels, which provides sufficient quality for high-definition (HD) video. This is the minimum resolution you’ll need for most TV broadcasters. But, if your subject will be far away from the camera, then it’s best to choose a 4K camera; you’ll be able to zoom in on your subject in post-production without losing your high definition.

Be careful, especially if you’re going to be investigating members of organized crime or others with big security budgets; they may have counterintelligence kits that can detect a hidden camera’s WiFi or that can deactivate any recording device by creating an electromagnetic field. Make sure you research what kind of security measures might be taken by your target before you go in with your hidden camera.

Reporters must carefully plan out their undercover tactics and intimately understand how to operate any hidden video or audio recording equipment. Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano

Ethics Concerns

Bruce Shapiro, the executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University, and an expert in journalism ethics, points out that alongside legal and sometimes physical risks, undercover reporting can bring significant ethical and reputational consequences. “To the reporter, the need to lie about your identity or purpose to get a great story may be obvious, but systematic deception can still be used against you to impugn your motivation or character,” he warns. “Ongoing deception is an ethical compromise, and needs to be engaged with great care before, during, and after undercover reporting.”

Shapiro lays out how journalists should think about ethical issues throughout the undercover reporting process.

Before

Prior to launching an undercover project, reporters or teams should ask three basic questions:

- Alternatives: Is undercover reporting really the only way to get this story — or simply the most expedient? Have you exhausted open source information, public documents, human sources, and other methods?

- Cost-benefit analysis: Is the story important enough to justify undercover methods and any potentially messy issues involved?

- Risk assessment: Have you fully laid out the possible risks to your team, your employer, and your sources? This may include physical threat and legal consequences, but also includes intense psychological stress for those undercover, reputational risk when your methods become public, and the possibility of blowback to your sources.

During

Whether you are working as a solo investigative reporter or as part of a team, undercover reporting is highly stressful work, and ethical challenges rarely end with the decision to go undercover. Maintaining an undercover role, worrying about exposure, and navigating daily reporting interactions can all take a toll, Shapiro explains.

- What ongoing support — whether legal, technical, editorial, or psychosocial — do you need during the undercover reporting phase?

- How will you know when it is time to pull out, and what’s your emergency plan if exposure or other threats are imminent?

- It is critical during undercover reporting to routinely debrief with trusted colleagues or your editor, talking over tough day-to-day reporting decisions. Undercover reporting demands shared responsibility.

After

Since the method of undercover reporting involves systematic deception, it is important in your final story to go to compensate with exceptional, even radical, transparency with readers or audiences. “Fully explain your decision to go undercover and the methods you used,” Shapiro urges. “Maximize attribution, avoiding casual use of anonymous sources. Hyperlink to documents and open source materials. Don’t leave your targets any hammer to knock down your credibility.”

Shapiro is by no means alone. Almost every journalism ethics code exhorts members of the press to be honest and transparent throughout their reporting process and to avoid deception of any kind.

These prohibitions on journalistic deception reflect the very real risks associated with surreptitious reporting and also highlight a generally negative reputation surrounding the practice in recent years – particularly in mainstream Western newsrooms. Media researchers attribute the dubious reputation of undercover reporting to a bevy of issues: frivolous tabloid press hidden-camera stings, reckless risk-taking by increasingly inexperienced newsrooms, rare cases of entrapment, rampant over-use in some countries, and abuse of the technique by political operatives. All these factors also draw a share of the blame for decreasing public trust in the media.

Value of Surreptitious Reporting

In her book “Undercover Reporting: The Truth about Deception,” Brooke Kroeger – a journalism professor at New York University – argues that the practice has been unfairly maligned and that it has, in fact, outperformed other forms of journalism in terms of accountability impact in the past 150 years.

Kroeger’s research has been expanded into an archive of hundreds of impactful “surreptitious investigations” – Undercoverreporting.org – in a collaboration with NYU Libraries that focuses largely on work from North America.

Kroeger says that while responsible undercover reporting should be rare, it has been too rare in recent years – and often avoided for the wrong reasons – leading to missed opportunities in otherwise impenetrable public interest cases. She adds that it has been particularly effective in exposing abuse and poor labor conditions in workplace environments.

She describes five types of surreptitious reporting, and says each one requires different levels of ethical and legal vetting.

- Consumer journalism testing. Kroeger says there are no ethical barriers to a reporter simply replicating a consumer experience. For instance, journalists could order a car repair to check for over-charging. While normal journalistic right-of-reply principles apply ahead of publication, she says no special vetting is needed.

- Eavesdropping. Kroeger says listening in on conversations – and disguising your reporting role to get into earshot – can be justified, where the unguarded comments of public officials can be shown to be essential in a vital public interest story. Here, legal advice about local and national privacy rules should be clearly understood if any recording devices are used. Sources should also be offered the opportunity to clarify or explain their comments, and audiences should be informed about how the quotes were gathered.

- Public institutions. Journalists are free to wander the same hallways the public can visit – but Kroeger says reporters sometimes need to subtly disguise their true roles to avoid challenges and extend their time in an institution. These passive tactics include avoiding press badges, not proactively declaring their reporter status, and using nuanced misdirection, like carrying a clipboard or dressing like other regular visitors. However, she says reporters should avoid active deception in these cases – like wearing a white coat and stethoscope, or wearing a specific symbol, tattoo, or partisan identifier. She emphasizes that reporters on these projects should immediately acknowledge their press status if directly asked or challenged. Kroeger says this method should involve ethical and strategy discussions with editors and an outside advisor.

- Hidden camera projects. Kroeger says in-depth legal and ethical advice should accompany the use of hidden cameras, both before and after filming, and that the evidence obtained should be contextualized by plenty of traditional reporting.

- Deep undercover. Kroeger believes taking a job under a false pretext, or posing as a role player in a scheme under investigation – especially one involving a crime – must always involve careful planning, and extensive legal, ethical, and safety vetting at every stage. Any alternative methods to gathering the facts must be actively sought.

Kroeger notes that women reporters, in particular, have made a major contribution to quality undercover reporting – most famously Nellie Bly, who exposed institutional brutality by posing as a psychiatric patient at an asylum in New York in the late 19th century.

Key Principles

- First, do no harm. Kroeger says journalists need to ensure their undercover work does not pose risks or deny crucial services to members of the community. For instance, she says reporters should not take a bed in a mental health institution or elder care center if that bed is needed by someone requiring real care.

- Never break the law. Journalists need to be briefed beforehand on the legal perils of their project and reporting strategy to know where the legal lines are drawn.

- Effort translates to trust. Kroeger says projects in which reporters have taken the time and energy to experience a situation for weeks or more typically generate more respect from audiences than brief, hidden-camera stings.

- Avoid direct lies – and especially any clear falsehoods in writing, or on any documents that require a signature. Kroeger says “artful dodges” and other forms of deception are acceptable in cases where it is required to obtain facts in matters of major public interest. “But you absolutely should avoid outright lying,” she advises.

- Consult outside advisors and legal advice when deciding on the undercover project, the acceptable strategies, and the publishable facts. In addition to your reporting team’s multiple editors, lawyers, and another independent advisor from outside your organization make for good sounding boards. “You need some very detached person to keep you on the straight and narrow,” she says.

- Rely on past undercover experience to inform questions for separate, data-driven stories that can be done from the newsroom. Kroeger says one undercover reporter noticed evidence of fraud while investigating a separate safety issue at a US hospital, which triggered a separate story. “You wouldn’t think to ask for those records unless you had witnessed [the problem],” she notes.

Successful Case Studies

- Kidnappers Association (2021 – Ukraine): Maria Gorban and journalists from nonprofit news site Slidstvo.info went undercover to investigate citizens’ allegations that they were kidnapped and held in rehabilitation centers after relatives claimed they were drug addicts and paid the center a few hundred dollars. Slidstvo journalists went undercover in two of these 50 centers across Ukraine and posed as relatives who wanted a family member forcibly held in the rehabilitation center.

- Psychologists Linked to US Ultra-conservative Organizations Provide ‘Therapy’ for Homosexuality in Costa Rica (2021 – Costa Rica): Journalists from openDemocracy and Radioemisoras UCR went undercover to investigate online “conversion therapy” sessions organized by the Costa Rican office of a US-based fundamentalist Christian organization.

- “All the Prime Minister’s Men” (2021 – Bangladesh): Al Jazeera’s Investigations Unit worked with a whistleblower to investigate allegations of corruption at the highest levels of government in Bangladesh. The team provided the whistleblower with hidden cameras to record the target, who had ties to the country’s prime minister. The investigation won a DIG award in 2021.

- Undercover Journalist as a Slave (2020 – Uganda): A female journalist went undercover for the Ugandan newspaper New Vision and was hired by a recruitment company to work in Dubai. As she reported in her podcast, she witnessed and experienced first-hand migrant mistreatment and the modern slave trade. Her goal was to warn Africans who want to follow the route to the oil-rich Arab countries about the risks in making the trip.

- “Exposing a Licensed Predator“(2021 – Ghana): Ghana’s investigative journalism nonprofit The Fourth Estate and undercover reporter Manasseh Azure Awuni secretly filmed a health practitioner who used his registered practice to sexually assault women seeking reproductive treatment and support. The story led to the proprietor’s arrest and confession.

- A Labor of Hitherto Untold Pain (2021 – Kenya): Reporter Naipanoi Lepapa went undercover for several months, posing as a parent keen to find a surrogate and, later, as a candidate willing to carry and give birth to a child for prospective parents. The piece was published on the Kenyan online media platform, The Elephant. Naipanoi’s investigations exposed claims of “coercion, exploitation, and intimidation of surrogates, apparent human trafficking of surrogate mothers and children, forced abortions, and identity forgery and fraud.”

- “Undercover: Inside China’s Digital Gulag” (2020 – China): The filmmakers behind this Frontline documentary worked out of neighboring Kazakhstan to investigate how Uighurs, China’s Muslim minority, are constantly monitored with the help of Artificial Intelligence. They hired a Chinese businessman to go into the Xinjiang region and act as their undercover proxy reporter, “since foreigners there are followed and Uighurs are surveilled.”

- “Betraying the Game”, (2018 – Kenya): Working for BBC Africa Eye, Africa’s best-known undercover reporter, Anas Aremeyaw Anas, spent two years reporting undercover to document corruption in Kenya and West African football. He caught on camera 100 football officials across the region accepting cash bribes to help fix matches.

- Inside a ‘Secret Abortion Clinic’ on WhatsApp (2018 – Brazil): For five months, a BBC News Brazil team gained access to and quietly observed a WhatsApp group that sold abortifacients – substances that induce abortion – and which gave advice to women that don’t have access to legal abortions in Brazil. The team found the group’s administrators had no medical training, and doctors interviewed by the reporters said that the procedure can be life-threatening.

- Goutte d’Or Editions regularly publishes undercover investigations in French like this exposé on racism and violence among the police in France and this story on the porn industry which claims to reveal “the recurring absence of consent, the non-respect of labor law, and practices contrary to human dignity.”

- My Four Months as a Private Prison Guard (2016 – US): This Goldsmith Award-winning investigation saw Mother Jones reporter Shane Bauer go undercover inside a private prison in the US state of Louisiana. During his time there, he documented rampant abuses and mismanagement. Not long after his exposé was published, the Justice Department announced it was ending its use of private prisons.

- Undercover in Temp Nation (2017 – Canada): This undercover report by the Toronto Star’s Sara Mojtehedzadeh and Brendan Kennedy offered readers an inside look at industrial baking companies and how they heavily rely on temporary help workers, who routinely confront unsafe labor conditions, little to no training, and low pay.

A Toronto Star reporter went undercover as a temporary worker at an industrial baking plant to document unsafe labor conditions, lack of training, and low pay. Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano

Cautionary Tales

Investigative journalists should be wary of going undercover as they may find themselves in life-threatening situations or facing — with their news organizations — a potentially costly lawsuit, since many countries consider the right to privacy stronger than press freedom.

- In Montenegro, investigative journalist Jovo Martinović spent 15 months in jail after he was arrested while working undercover on a story about arms trafficking in the Balkans. He was later sentenced to one year in prison on drug charges. Martinović has denied the charges, and previously told the Committee to Protect Journalists that he believed they were in retaliation for his reporting.

- One notable example from the 1990s involved ABC News reporters who lied on their resumés in order to get hired by the US grocery store chain Food Lion. They subsequently videotaped mishandling and repackaging of expired meat in the grocery stores. After their report came out, however, the network was sued in what became a landmark press freedom case. While the fraud charges against the TV network were eventually rejected, the ABC News producers who conducted the undercover reporting were found guilty of trespassing and ordered to pay millions of dollars in damages. Eventually, a federal appeals court reversed part of that ruling and many of the fines.

- Journalists might also need to deal with the heavy emotional toll that undercover reporting can exact, as in this case of The Quint, an online website in India. Reporters secretly filmed an Indian soldier complaining about the chores he was forced to do for a superior. After publication, the soldier committed suicide. In this journalistic analysis, Poynter concluded that the story of Indian soldiers performing menial chores for their superiors had already been broken, so singling out this soldier’s experience in an undercover sting didn’t advance the story and was unnecessary.

First-Hand Lessons from the Field

By Rowan Philp

I pursued just four undercover investigations during my 15 years as a senior reporter in South Africa – and made significant errors in three of them, all of which involved rushing the process. Some of these errors remain common in newsrooms, and can be avoided.

Don’t Rush the Undercover Operation

In one case, my news editor agreed that I could pose as a potential buyer to expose a suspected human trafficker in Johannesburg. The man unexpectedly suggested we meet that same night, and I, using an alias, felt pressured to agree. So I rushed out to the meeting without any proper planning. At the end of the meeting – at the exit to a pool hall the man appeared to own – he asked for my landline number. Panicked, I blurted out the number for my newsroom direct line, which goes straight to voicemail. The man calmly looked at me and, to my astonishment, said he recognized the prefix of the number I’d given him — as the prefix switchboard number for my newspaper! Fearing physical assault from his bouncers, I simply turned and fled down the street, and the story was lost.

Lessons Learned:

- Take the necessary time to plan – and don’t allow your subject to dictate the start of your investigation.

- Cite a burner phone or Google Voice number to your subject, never your own.

Consider Traditional Methods Instead

In a second case, my newspaper decided to investigate a local casino that, contrary to its stated policy, was allegedly allowing the children of compulsive gamblers to be dropped off at the property almost every school night. Sources claimed that children were left at the small care center up to seven days a week, with some left to roam unsupervised and sleep on the floor, while others were even left in cars in the parking lot. After being intentionally vague about my daytime job when interviewing with the casino’s hiring manager, I was brought on as a volunteer at the child care center, and spent 10 evenings there over several weeks – an experience which confirmed many of those allegations and surfaced other forms of neglect. The resulting story made an impact: the casino’s executives did not dispute the findings, and agreed to overhaul their child care policies and fund new social programs. But several problems soon emerged. Our story failed to disclose my undercover work to readers, which left facts unattributed. And we realized, too late, that this did not need to be an undercover investigation: that I could likely have found sources like ex-employees, casino CCTV video footage, or internal documents to confirm the earlier allegations from parents.

Lessons Learned:

- Before launching an undercover project, have one more team meeting and thoroughly test the claim that undercover reporting is the only way to gather the information you need in reasonable time.

- Substantially increase your planning resources and ethical and legal input when considering any undercover work involving children, other victims, or vulnerable populations involved in the story.

- Always be transparent with audiences, and let them know exactly how you gained access, and why.

Avoid Letting a Scoop Mentality Drive Publication

In a third case, my news editor was concerned that there may have been a miscarriage of justice in the murder conviction of a woman in Botswana, who was on death row. Having been barred from any access to the woman by restrictive press laws in the country, I gained access to her cell through a ruse that led prison guards to believe I was her attorney – by dressing the part, and explaining that I needed to brief her on legal issues. Upon meeting, I immediately identified myself as a reporter and she said she was eager to share her story. The interview did provide strong new evidence that the woman had not been mentally competent to stand trial, was physically incapable of having committed the murder, and was likely the victim of legal malpractice.

However, the story failed to gain any traction, as the justice authorities were unmoved, and the woman was hanged two months later. A senior government official in Botswana claimed that I had violated the law in gaining illicit access. In hindsight, I realized the story critically lacked additional reporting, and was published prematurely. It was also written from the first-person perspective, which – while perhaps adding to the human interest drama — made it difficult to weave in third-person sources. In addition, I was not aware my deception could potentially violate local laws.

Lessons Learned:

- Resist the temptation to immediately publish an exclusive undercover scoop – especially when the stakes are high for the subject.

- Recognize the limits of the first-person perspective and how it could hamstring your final product.

- Make the successful undercover interview count by taking the time to complete the project, and be sure to follow the surreptitious work with on-the-record traditional reporting, and careful vetting.

- Check with local legal experts on potential legal violations when going undercover in a foreign country.

Sometimes the Simplest Methods Are Best

It is perhaps telling that my sole fully successful undercover project did not involve active deception or lying. Instead, it involved eavesdropping on a secret meeting, where I allowed each party to believe me to be a member of the other.

This exclusive story on Russian-South African nuclear power plant talks was obtained using the most basic undercover reporting tradecraft. Image: Screenshot

In 2014, I investigated rumors that the South African government was secretly planning to purchase eight nuclear power reactors from Russia – an illicit deal at a ruinous price tag of approximately US$70 billion. The government, however, had denied that any negotiations were underway. To investigate, I tracked what appeared to be a visiting Russian atomic energy delegation to a remote mountain resort, and – dressed in a suit – I simply followed them into a meeting room, where South African officials were gathered.

The negotiations I recorded included detailed discussions of offset deals, technical safety features, and the disposal of nuclear waste. Eventually, officials realized I was not with either delegation, and ejected me from the room. After securing the evidence I’d collected, I approached both delegations, announced myself as a reporter, and asked for comment. South African officials reluctantly confirmed the negotiations. My follow-up reporting then revealed that – despite his denials about any history with the Russian agency — then-South African president Jacob Zuma had previously championed a nuclear fuel deal with a subsidiary of that agency. This scoop was followed by extensive investigative reporting on the secret negotiations by other journalists, which, together, led to the eventual scrapping of the nuclear deal.

Strategies that Worked

- The passive eavesdropping method worked well because (1) we could show that there was no other way to gather details on an issue of vital national importance; (2) I disclosed my identity as a reporter to the subjects immediately after recording their negotiation, and gave them an opportunity for a full response; and, (3) we were fully transparent with readers, explaining how all the facts had been gathered.

- We were careful to augment the brief undercover fact-gathering with traditional reporting, and then followed-up the scoop with a traditional investigation into the agency and the government’s prior secret nuclear negotiations.

- We deepened the story’s impact with radio interviews, and collaborative contact-sharing with other newsrooms.

Material gathered thanks to GIJN staff: Toby McIntosh, Benon Oluka, Ana Beatriz Assam, Miraj Ahmed Chowdhury, Mariel Lozada, Amel Ghani, Alim Kholikul, and Deepak Tiwari.

Other Undercover Reporting Resources

- A Guide to Undercover Investigative Journalism for Multimedia Outlets, a webinar organized by IJnet with BBC Africa Eye’s Charlie Northcott and Gbolahan Peter Macjob, a multimedia producer, presenter, and reporter with the BBC World Service.

- The Prix Italia Masterclass talk with the creators of: “Undercover: Inside China’s Digital Gulag,” Hardcash/ITV (UK), and PBS (US), an investigation that won a Peabody Award.

- An animation on the story of one of the first reporters to go undercover, Nellie Bly, Undercover in an Insane Asylum: How a 23-Year-Old Changed Journalism produced by GIJN member Center for Investigative Reporting.

Additional Resources

Becoming a Butcher: Lessons From Working Undercover

From #MeToo to Going Undercover: Tips from Women Investigators

How They Did It: Feminist Investigators Go Undercover to Expose Abortion Misinformation

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. For 15 years, she wrote and produced documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for over 100 media outlets, including the BBC, AP, The New York Times, PBS, Deutsche Welle, and Al Jazeera.

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. For 15 years, she wrote and produced documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for over 100 media outlets, including the BBC, AP, The New York Times, PBS, Deutsche Welle, and Al Jazeera.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.