10 Questions

An Unexpected Journey: Sports TV Host to Investigative Journalist and Star African Correspondent

Philip Obaji Jr has— often at great risk — reported on Boko Haram, human trafficking, and Russian activities in Africa.

Philip Obaji Jr has— often at great risk — reported on Boko Haram, human trafficking, and Russian activities in Africa.

Finding victim-survivors to talk about human trafficking is difficult. Three journalists at GIJC23, who cover human trafficking and irregular migration, shared tips on how to find and protect sources.

A reporting team provides the backstory of the Guardian’s years-long investigation into the world of online child sex trafficking.

Organized crime is a global phenomenon. But Africa, with its deep-seated corruption and “resource curse,” is particularly hard hit.

GIJN’s Africa editor, Benon Herbert Oluka, presents his Editor’s Picks for the best investigative reporting from sub-Saharan Africa in 2022, which demonstrated the curiosity, ingenuity, bravery, and technological know-how of Africa’s top investigative journalists and teams.

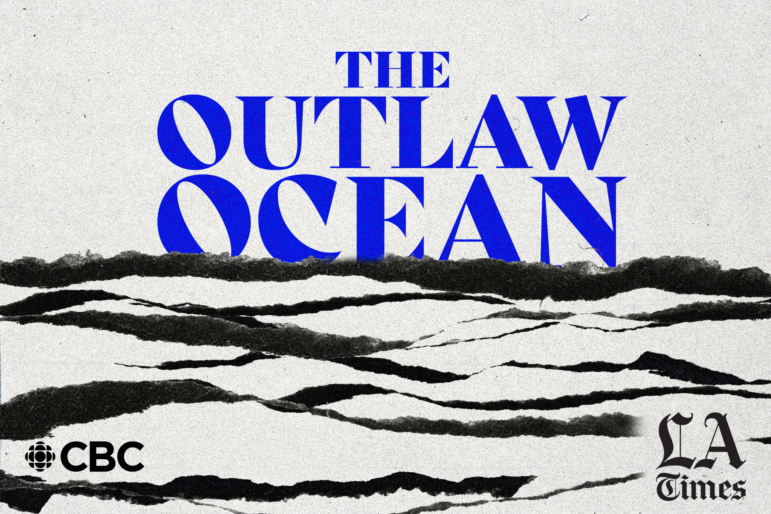

The Outlaw Ocean Project — a nonprofit journalism organization that reports on the “watery two-thirds” of our planet — used material from several years of investigations on the high seas to create a new, seven-part podcast.

At a JournalismFund.eu webinar, journalists Annie Kelly and Ian Urbina spoke of their experiences documenting human trafficking around the world.

Every year thousands of migrants cross one of the most dangerous borders in the world: the Darién Gap, a magnificent but deadly rainforest that connects Colombia and Panama. GIJN spoke to a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, and one of her teammates, who trekked through the jungle to investigate what happens en route.

Katie McQue, a British freelance journalist that spent five years reporting from Dubai covering human rights and migration alongside her “business” beats of energy, healthcare, and finance, speaks to GIJN about her work and the best practices reporters can adopt when covering forced labor and human trafficking in the region.

Over the last 12 months investigative journalists in Bangladesh uncovered cases of corruption, abuse of power, money laundering, and institutional negligence. The biggest topic last year, as in previous years, was corruption. But in picking the top stories of 2021, we also considered significance and novelty, the diversity of issues covered, impact, and a focus on the vulnerable and marginalized sectors of society as much as the depth and techniques used in any investigation.