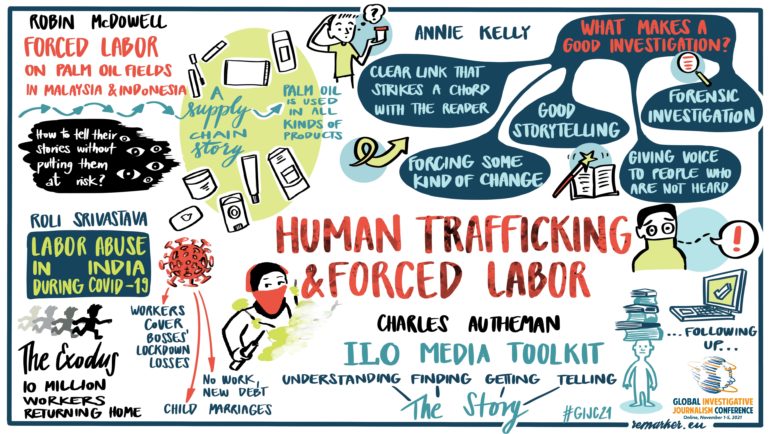

The Migration and Human Trafficking panel at GIJC23. Image: Wolf France for GIJN

Finding — and Protecting — Sources for Human Trafficking Investigations

Read this article in

There are more than 50 million people trapped in some form of human trafficking and modern-day slavery around the world, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Human trafficking and its related issue of forced labor are deeply embedded in the supply chains of the clothes we wear and the food we eat.

For journalists, finding victim-survivors willing to share their story for publication can be the biggest hurdle to reporting on human trafficking.

During a panel at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) in Sweden, three journalists talked about how they earned the trust of victim-survivors for their reporting on human trafficking and irregular migration from, respectively, the coastal borders of Greece, across Finland, and the route between India and Europe.

Paavo Teittinen, a journalist for the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat, exposed the extent of human trafficking and forced labor in Finland, and how the police failed to fully investigate the problem. The story prompted an inquiry and criminal proceedings against the police.

Teittinen interviewed dozens of people working in Nepalese restaurants and tomato farms, and trapped in forced marriages, for his story The Investigation is Closed, and reviewed almost 100 case decisions across police departments all over Finland.

“If you want to have maximum impact don’t settle for a few individual stories. There are powerful interests who always say, ‘Oh it’s just a few rotten apples,’” said Teittinen.

When it comes to looking for victim-survivors, Teittinen suggested talking to lawyers who specialize in human trafficking cases and NGOs who work both at the grassroots level and with law enforcement.

Reflecting on his experience covering trafficking, Teittinen said there is a “big disconnect” between the imagery of human trafficking coming from Hollywood and popular culture, and reality. As an example, Teittinen said that Google searches for human trafficking will often yield images of people tied to a radiator in the basement or other similar images of forced detention.

“The vast majority of trafficking victims are held in their situation by much more subtle forms of control,” said Teittinen. “I think it’s very important for journalists to understand this, else we don’t realize that a human trafficking victim could have been anyone we passed on the street this morning on the way to this conference center.”

Look for Sources within the Community

Teittinen also explained that since trafficking is a hidden form of exploitation that usually happens among migrants belonging to various ethnic groups, journalists need to “find someone who can approach victim-survivors for you.” Interpreters or community organizers who belong to a migrant group or citizens/residents with migrant ties and can speak the language can help link journalists to victim-survivors.

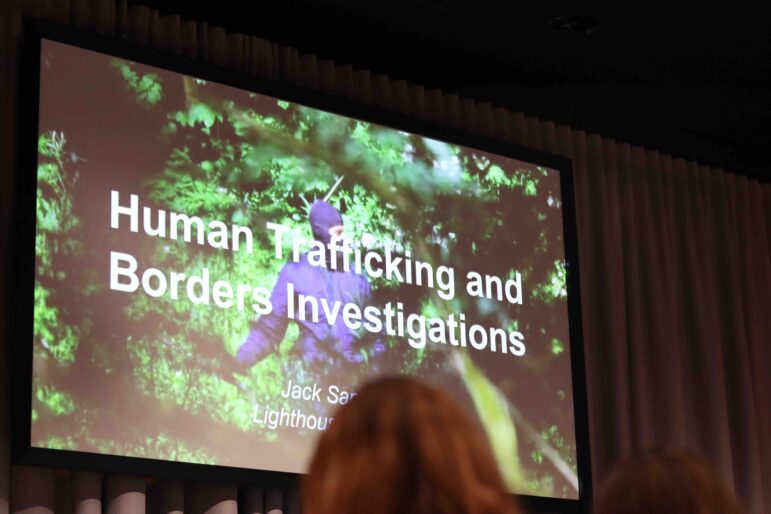

Jack Sapoch, an open source digital investigator for the Netherlands-based Lighthouse Reports, agreed that reaching out to communities impacted by trafficking is a good way to get sources.

Jack Sapoch (far right), an open source investigator with Lighthouse Reports, talks about his exposé on migrant abuse along the Greek coast, at the Migration and Human Trafficking panel at GIJC23. Image: Wolf France for GIJN

For the Lighthouse Reports transnational investigation We Were Slaves, which revealed how Greek authorities use asylum seekers to forcibly return migrants to Turkey, Sapoch and his team spoke to six people from Syria who entered Greece hoping to seek asylum.

“They were forced to carry out these illegal deportations for Greek authorities who didn’t necessarily want to take the risks themselves to do this work,” said Sapoch.

The Lighthouse team established contact with the victim-survivors by working with a social media group comprised of people from Syria and the Arab region on their way to Europe, which “then opened the door to get in touch with some other people,” Sapoch explained.

In addition to the interviews, Lighthouse Reports collected open source visuals of police stations in the heavily militarized zone between Greece and Turkey, and combined them with selfies the victims took inside the stations to reconstruct 3D models of the detention facilities. Official documents and interviews further corroborated the harrowing experiences of migrants and asylum seekers.

“States typically frame human trafficking quite aggressively as the primary cause of violence along migration routes and borders, but state authorities play a huge role in violence and misery along these routes,” Sapoch pointed out. “As some of our investigations have shown, state authorities actually have explicit links to human trafficking networks.”

Protect Sources and Earn Their Trust

Indian journalist Pari Saikia discusses her investigation into Punjabi women being trafficked into Europe. Image: Wolf France for GIJN

For Pari Saikia, an independent journalist based in India, finding victim-survivors for her cross-border investigation about Punjabi women being lured to jobs in Europe by traffickers masquerading as travel agents was a long journey — literally.

A Punjabi man who returned to India because of COVID-19 told Saikia about how more and more Punjabi women were being trafficked to Italy and referred her to some people.

Saikia went to Italy hoping to conduct interviews, but they were hesitant to share their story. Saikia gave everyone she spoke to her number and told them to get in touch when they were ready to talk.

Back in India, Saikia and her reporting partner, Sona Singh, received calls and messages from trafficked women who were interviewed via Signal and WhatsApp.

“Human trafficking victims may not want to talk right away. You have to give them time and space to earn their trust,” said Saikia.

Saikia and Teittinen added that some victim-survivors may be wary of speaking to journalists.

“Some journalists promise victims help in exchange for an interview but they end up with nothing,” said Saikia, who makes it a point to connect her sources with lawyers or NGO groups.

“I’ve seen some horrible cases where sources think that they are speaking anonymously and as soon as the article is published, everybody in the community instantly knows who they are,” said Teittinen, who urged journalists to be extra vigilant about minor details that can lead to victims being identified by people who know them.

Saika further stressed the importance of securing informed consent. “We have to inform them when the story comes out, they might face repercussions from their own community.”

Ryan Heman, director for the forced labor and human trafficking portfolio at the US-based nonprofit Humanity United, spoke to GIJN after the panel about how survivor voices can inform other solutions to human trafficking — as alternatives to law enforcement.

“Journalists often interview survivors about their experiences but turn to NGOs and rights groups as experts for possible solutions. Survivors, because of their lived experience, are also experts who can propose solutions,” he explained.