J. Fernando Rodrigues, Diana Cariboni, and Mamdouh Akbik speak after the undercover investigations panel at GIJC23. Image: Leonardo Peralta for GIJN

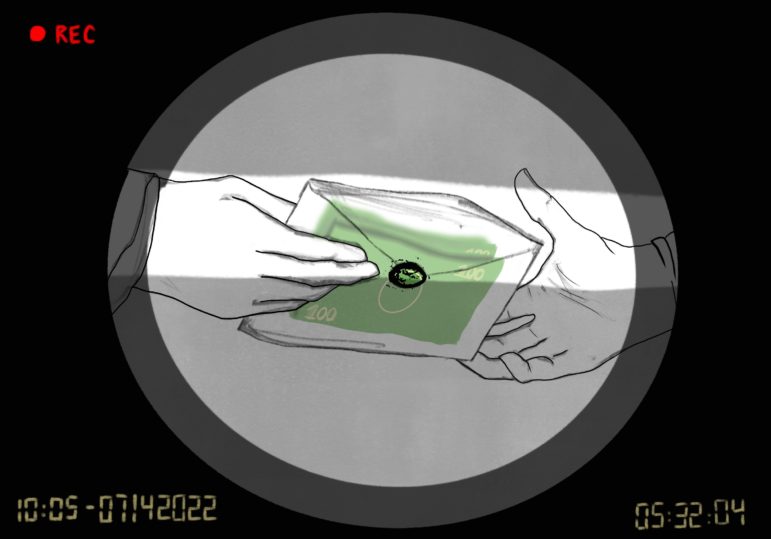

Reporting of the Last Resort: Tips for When — and How — to Conduct Undercover Investigations

Read this article in

Certain stories require access or information that interviews, documents, or data cannot provide. If a reporter has tried all other options and still needs that piece of secret information or recording that only an insider can get, in some circumstances they can consider going undercover.

“Going undercover is not a natural thing for journalism,” said Diana Cariboni, Latin America editor for openDemocracy, speaking at a session on undercover reporting at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC23) in Sweden. “It’s something that we do as a last resort, when we know that we can’t possibly get the information that we need.”

Also speaking on the panel, moderated by Brazilian journalist J. Fernando Rodrigues, was Naipanoi Lepapa, a freelance investigative journalist in Kenya, and Mamdouh Akbik, an investigative film producer for BBC Arabic. The speakers shared their experiences going undercover and pointed out some tips and best practices — ethical, practical, safety-related — to help journalists considering similar methods.

(For a more detailed look at the practice and ethics of this investigative method, see GIJN’s Guide to Undercover Reporting.)

When to Go Undercover

Cariboni was part of a cross-border team that exposed crisis pregnancy centers and conversion therapy centers around the world — backed by US-based organizations and religious groups that target women and LGBTQ individuals with disinformation about abortion and homosexuality.

Crisis pregnancy centers use misinformation and emotional manipulation to convince women seeking abortion services or medical advice to carry their pregnancies to term. OpenDemocracy reporters who went undercover as pregnant women at these centers were told, among other false information, that abortion increases the likelihood of developing cancer and mental illness and that they need their partner’s consent to get an abortion.

When Cariboni’s colleague discovered one of these centers in a public hospital in Italy, the team decided to put together a global investigation. They decided to go undercover for three reasons.

- To avoid exposing the reporters. These centers reportedly harass people who approach them, especially if they have provided their names and contact details.

- The legal status of abortion in various countries makes inquiring about them dangerous.

- Reporting undercover makes it easier to operate on a global scale without compromising the investigation.

The investigation found more than 700 affiliates of a US-based organization, and managed to contact more than 30 of these centers in 18 countries on four continents.

For the investigation into conversion therapy centers, reporters would pretend to want to “correct” their sexual orientation due to suffering or family pressure, then pay for online sessions in which priests or psychologists would promote abstinence, fasting, and praying.

The team decided to go undercover in this case because survivors of this kind of therapy rarely identify the groups of individuals responsible — due to trauma, fear of persecution, or because their families are complicit.

OpenDemocracy’s reporting is based on the following ethical guidelines:

- Don’t expose or re-victimize people.

- Don’t expose volunteers or rank-and-file staff activists.

- Do expose wrongdoing activities.

- Do expose organized groups involved in these activities.

Cariboni also shared general tips for undercover investigations:

- Consider small pilot phases

- Develop tools and resources

- Prepare cover stories and identities

- Test equipment and rehearse

- Be prepared for surprises

- Do a risk assessment

- Don’t let any undercover reporter go alone

- Have a plan if your cover is blown

- Mental health support is important

Assess the Risks

Naipanoi Lepapa had learned about agencies marketing surrogacy services in Kenya, where the industry is not regulated. The lack of official information or sources willing to talk forced her to take drastic measures: “I want to emphasize that, had I another choice, or another way of getting information, I would not have gone undercover,” said Lepapa. She added that this last resort should only be used in cases where there is a public interest defense.

Lepapa wanted to find out who was benefiting from the surrogacy industry; where offices were located; relevant names; the condition of women who became surrogates; and details on how children were transferred.

Lepapa said she always needs a well thought-out plan — which includes evaluating the risks. So she follows a set list of tasks, questions, and risk assessments.

- Make a list of identified risks connected to the story

- Who or what will be at risk? It could be sources, community members, staff, vehicles, etc.

- Vulnerable points. Is the threat via the internet or communications, or something else? Is it confined to one or more areas?

- What will the impact be?

- The likelihood of a risk coming to pass — from 0 or very unlikely to 5 or currently happening.

- The impact an investigation could have, from 0 to 5.

- What capacities a reporter has to help reduce or manage the risks.

The above considerations should help a reporter elaborate an action plan to help manage any possible incident. “You should always plan well and prepare because you’re going to be in unsafe positions. Not just you, but also the people that you’re working with,” said Lepapa.

When contacting sensitive sources undercover in person it’s important to:

- Plan ahead where the meeting will take place and elaborate an exit route.

- Keep the engagement short and brief.

- Wear loose clothes in order to reveal as little as possible of the reporter’s own appearance.

- Choose a pseudonym for yourself.

- Have an extra set of clothes and even any other hygiene products you might unexpectedly need, in case you have to spend the night away from home.

Lepapa noted that building relationships and trust with sources takes time. For her investigation of the surrogate industry in Kenya, being charming, talking off-topic, and not being too direct with sources helped her get useful information.

Advice for Undercover Filming

With a team of talented journalists and hidden cameras, Mamdouh Akbik has helped produce award-winning films that wouldn’t have been possible to make by filming openly. In 2020, he produced an undercover documentary in which a reporter filmed evidence of child abuse in more than 20 schools in Sudan.

“Undercover is a very powerful tool, especially now in this day and age of fake news and disinformation,” said Akbik. “Having this precise piece of information, that actually can prove wrongdoing, is really important, but we do it in a very careful way.”

Working for the BBC requires high ethical and legal standards to protect the journalists and the organization. Undercover filming, he said, often involves violating people’s privacy, which could have legal consequences in some countries.

He says that when deciding whether or not to go undercover he considers whether the story is in the public interest, if there are any viable alternatives, and says that any undercover operation cannot be a fishing expedition. To even consider taking the risk of going undercover, there should be a very high expectation of obtaining prima facie evidence — like proof of wrongdoing.

“It’s like we’re walking on a thread… between the public interest and the right to privacy. So we always think about not just following the rules, but to work the ethical way,” said Akbik.