How Reporters Exposed the Spies Implicated in the Navalny Poisoning

Read this article in

A wall chart showing how Bellingcat investigated the poisoning of Alexey Navalny. Image: Courtesy Bellingcat

No law enforcement agency in the world announced a criminal investigation into the attempted murder of Russia’s leading opposition figure, Alexey Navalny, after he was poisoned with a chemical weapon on August 20 last year.

In response to this obvious lapse in accountability, reporters from investigative nonprofit Bellingcat and Russia’s The Insider, supported by CNN and Der Spiegel, stepped forward — and needed just three months to implicate Russia’s FSB domestic security service for the Novichok nerve agent attack against President Vladimir Putin’s chief rival.

FSB agents are experts in counter-surveillance — and yet the joint investigation named the three members of the team who trailed Navalny, and the five scientists and senior intelligence officers who supported their operation. A CNN reporter even confronted one of the FSB operatives at his Moscow apartment. Navalny has since recovered from that attack — which made headlines around the world — but is now reportedly suffering from numerous medical issues after being sent to prison in Russia in what the US State Department calls a “politically motivated” prosecution. Russia has repeatedly denied any responsibility for the Navalny poisoning, but the European Union and the US have imposed sanctions on Moscow for both the poisoning and persecution of the opposition leader.

To investigate the involvement of Russian’s security services, the joint investigation chose to purchase black market data — an ethical last resort in journalism — to supplement a mix of open source tools, social media search, and traditional reporting methods.

On December 14 last year, Bellingcat — a GIJN member that focuses on open source intelligence — stated the following: “No law enforcement agency in any country is currently investigating the poisoning of Alexey Navalny.” And Christo Grozev, a lead researcher for Bellingcat, told GIJN that — as of early April 2021 — no law enforcement officer had contacted either the victim or the immediate witnesses since that statement, and that, therefore, this continues to be a crime that only journalists have fully investigated.

In a March 25 GIJN webinar, Grozev and Roman Dobrokhotov, editor-in-chief of The Insider — one of Russia’s few-remaining independent investigative sites — shared tips on how to effectively and ethically navigate data markets and intrusive personal data tools in the rare investigations that require them. They were joined on the panel by Dorothy Byrne, editor-at-large at Britain’s Channel Four public service television network, and a trustee of the Ethical Journalism Network, who explained how newsrooms should test their potential investigative toolboxes against ethical checklists.

One striking takeaway for the webinar audience — which drew 319 journalists from 64 countries — is that the Navalny investigation was built largely around logical assumptions, previous chemical weapons probes, and classical investigative questions.

Dobrokhotov and Grozev say they targeted data based on questions like these: What passengers booked flights that mirrored Navalny’s flights from Moscow to the city of Novosibirsk on the week he was poisoned? Who among these passengers traveled together? Which of these showed the characteristics of false identities, like missing passport data? Who traveled onward to the city of Tomsk, where Navalny was attacked? Who did these people call — and were any of the individuals answering those calls connected to Russia’s chemical weapons program?

While much of the downstream connections and verification could be done with open source tools and social media search, some of the datasets needed — like passenger manifests and telephone billing records — could only be obtained via Russia’s illicit data markets.

“Some of these databases are not publicly available, but in fact it is quite easy to get access to them on the black market,” Dobrokhotov explains.

Although some of these datasets are specific to Russia, Dobrokhotov says investigative reporters in other repressive countries can, if necessary, take advantage of the same data phenomenon: that authoritarian governments almost always create corrupt bureaucracies, and that this environment can produce data leaks to expose crimes by those same governments.

“Roman [Dobrokhotov] has always said that Russia is actually one of most transparent societies, because you can buy fairly centralized data for not a lot of money, which is typical of these markets,” Grozev notes.

Dobrokhotov says The Insider also drew on databases and lessons learned from previous investigations into the use of the Novichok nerve agent, including the poisoning of former Russian military officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, in the UK in 2018.

“This is how we learned to use Russian databases to track these spies, and understand what methods can be used,” Dobrokhtov explains. “In August 2020… we thought the same institutions were also probably manufacturing Novichok for those who tried to poison Navalny — maybe it’s not GRU (Russian military intelligence), but FSB (Russia’s state security agency),” he adds. “That was when we started looking to phone call data, and metadata — this is the data Russian operators collect: you can see not only who the person was talking to, but where they were, with geolocation.”

Dobrokhotov says the final clue they needed came when Navalny himself called one of the FSB operatives and tricked him into a 40-minute confession. He says this call also added one new detail: that operatives placed the poison on Navalny’s underwear, in the belief that this was the one clothing item that only the target was likely to touch.

Bellingcat’s Grozev — whose work includes investigations of the Skripal poisonings and the 2014 shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 — makes this broader, useful point: that even professional spies can be tracked closely by reporters, partly because they make some of the same human mistakes that anyone else might make.

For instance, they can be lazy. Grozev notes that several undercover spies routinely booked parking sessions close to the FSB headquarters in Moscow, while some even registered their personal vehicles to their agency address.

Also, they can be sloppy. He says passports given to intelligence officers as part of their cover identities are often issued with unlikely dates of birth, or with sequential passport numbers, where the last digit can flag other spies in the same unit.

And they can be gullible — like the operative who was tricked into confessing his role in the cover-up on the phone.

The toolkit used by these enterprising journalists amounts to a virtual gold mine of open source — and not so open source — techniques. First, consider the open source tools used by Bellingcat’s Grozev on the the Navalny poisoning.

Open Source Tools Used

- Reverse phone-search bots on Telegram or smart phone apps. These bots — programs that execute a specific task according to the user’s instructions — included GetContact, TrueCaller, and SmartSearch. “These allow you to look up a person based on the phone number you put in, and they usually work on the principle of number sharing,” Grozev notes. “If you download X app on your phone, it extracts your contacts as described in your list and pools them. So it could be as [unhelpful] as a number linked to ‘Mother,’ or something as specific as ‘Yevgeny from the FSB’s night department.’”

- Reverse phone-search for background data. These included EyesofGod and QuickOsintBot. “These are Telegram bots that provide a bit more — maybe addresses and additional data,” Grozev explains.

- “Worth-a-try” platforms to find identities. These try-your-luck options included Viber, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Skype. “For instance, if you type a number into the search bar in Skype, you may just end up with the name of the person, if they connected their phone number to Skype,” Grozev adds. “With WhatsApp, you might end up with a photograph connected to the number, and then you can do a face search.” One of the phone numbers researched using these methods was actually listed as a named individual “from the FSB.”

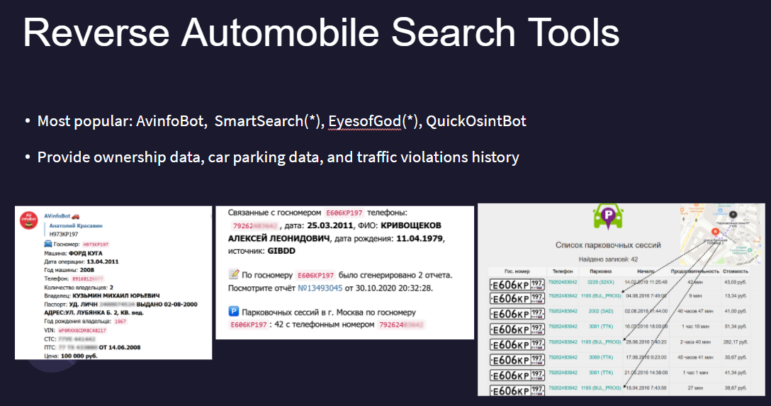

- Reverse vehicle-search bots. These included AvinfoBot, SmartSearch, Eye of God, and QuickOsintBot, which provide ownership data, car parking data, and traffic violation histories. “These can be extremely useful in tracking down the movements of a person, and to see if they’re connected to a secret service, and which one,” says Grozev. Bellingcat found that one of the people who spoke frequently with the chief scientist of a lab that manufactures the Novichok nerve agent had a car registered to FSB headquarters. Using these tools, Bellingcat discovered that one suspect’s phone was connected to 42 parking sessions — and geolocated many of those sessions to a parking area just a few blocks from the FSB.

Reverse vehicle search tools played an important role in the Navalny poisoning investigation, as data on parking, registration, and traffic violations provided additional evidence that several individuals with false identities were state security operatives. Image: Courtesy Bellingcat

- Face verification and comparison tools. Grozev hails the “the very reliable Azure tool from Microsoft.” He adds that this platform was used to find the true identity of one FSB operative employing a false passport identity, where the app gave a high confidence score for the same face appearing on the Facebook account of a woman who turned out to be his wife. In an image on her social media account, the man is seen on a beach, wearing a large, yellow, inflatable toy around his head. It was a stark, and instructive, real-world contrast to the fictional James Bond image of spies with a license to kill.

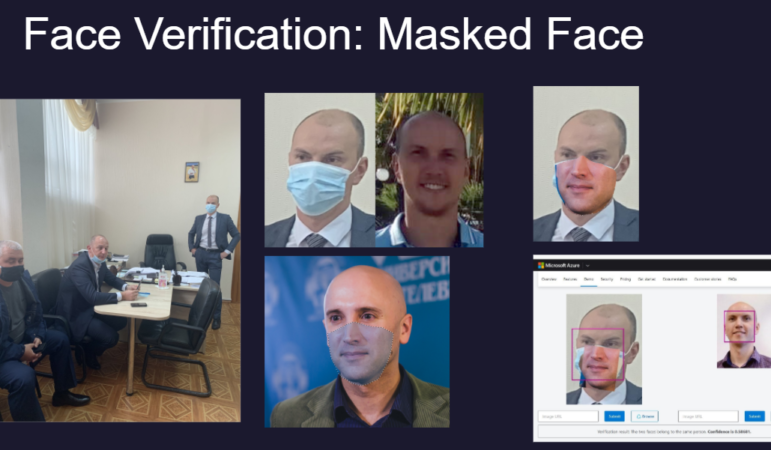

- Substitution technique to identify masked faces. Grozev says the team had a theory about the involvement of a masked man seen in one image in the same place where Navalny was being treated for poisoning. They thought he might be a match for a suspect whose full face image they had found on a social media account. But how could they build confidence that he was the person behind the mask? “We had to supplement the lower part of the face with some other guy — for fun, we just took the lower face of a British journalist, Graham Phillips, and we added it to the [masked part] of the suspect’s face,” Grozev explains. “We knew we would not get a complete match, but we did achieve a 57% match, which according to Microsoft is sufficient to conclude that this is a match.” Note that this technique, and Microsoft’s estimates, are not sufficient for ironclad verification, but can be useful in building a reporter’s confidence to follow a lead.

To find whether it was likely that the standing masked man (left image) was the same person their investigation found on social media, Christo Grozev substituted the masked portion with the lower face of a friend, UK journalist Graham Phillips (lower central image), on the Azure facial recognition tool. Image: Courtesy Bellingcat

- Reverse face search. These included FindClone, Search4Faces, PimEyes, Yandex, and SmartSearchBot. Grozev says one of these reverse face search engines helped establish that one suspect had a medical background, thanks to a Facebook image showing the man wearing a stethoscope. This clue caused Bellingcat to actively search for medical backgrounds among the other suspects, and they found three more examples.

- Yandex and Google search tricks. “These are just regular search engines that sometimes provide more data than intended,” Grozev notes. Yandex’s auto-fill function predicts common search terms made by other users, even if no actual information exists on its pages. So Bellingcat could see, for instance, that many people suspected that one individual was an FSB officer.

- Leaked travel databases. “We consider these open source because we downloaded them from [files] previously leaked, and we didn’t have to buy them specifically,” he says.

- Leaked people databases. These included Cronos and Larix. “In Russia, and also in the Ukrainian and many eastern European markets, there are a lot of tools for looking for historical data on people — residential addresses, former passports, and so forth,” Grozev adds.

Records Bought on Russia’s Data Markets

Key to the investigation, Grozev says, were private records purchased for small sums on Russia’s data markets. Among them:

- Telephone logs, or billing records.

- Passenger manifests for planes and trains. “In Russia, you can acquire these manifests from data brokers,” Grozev says. “You have to find an anchor passenger and look for common patterns.” Bellingcat identified potential suspects from flights that mirrored Navalny’s flights — and the team also looked for the timing of the bookings made by passengers on those manifests. “We saw that two other people had booked their flights at exactly the same time as our [first suspect], on the day before their flight, at 14:34,” he explains. “We looked deeper at those two names and found they were fake identities — they didn’t exist in any of the passport databases, and the birth dates of these guys [were suspicious].”

- Travel and ticketing histories. This included a Russian database known as Magistral. “These you can acquire either from whistleblowers working for the police, or from data brokers in Russia — the full travel data on a person, based on tickets,” says Grozev. He explains that this data showed that an intelligence agent using the false name “Frolov” bought a ticket timed to arrive in Novosibirsk hours before Navalny’s plane was due there, and that he later booked a flight back to Moscow from Navalny’s next destination, Tomsk, for the day after Navalny was poisoned.

- Passport data. “Every Russian citizen has a passport file that includes not only their current passport photo, address, and registration, but also previous data linked to previous passports,” he notes.

“By following not only the flights taken, but also the flights not taken, you can create a pretty good hypothesis for what was happening in the planning of these secret operations,” Grozev explains.

Ethical Considerations

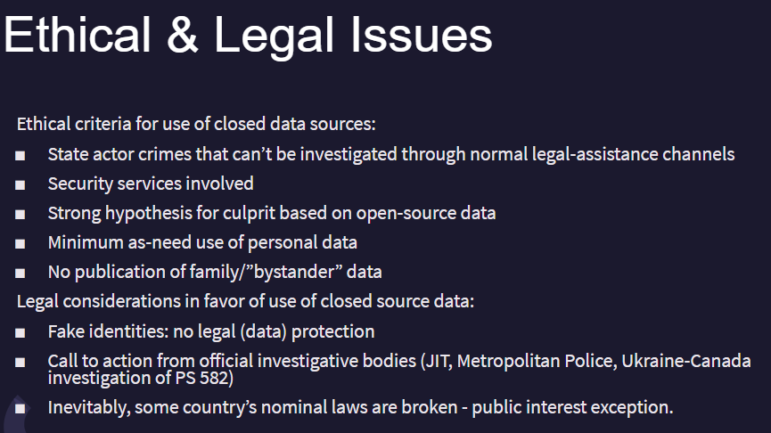

While the story’s scope and impact are impressive, the broad use of personal data purchased on the Russian black market raises numerous ethical issues. The Ethical Journalism Network’s Dorothy Byrne — who has contributed to various books on media ethics — says news organizations should produce ethical guidelines for controversial fact-gathering practices, just as they have written protocols for reporting in hostile environments.

“I think these brilliant and innovative techniques that are now available mean we have to think seriously as journalists about what the ethical dilemmas are,” she says.

Byrne cautioned that journalists should, at a minimum, consider the following questions before embarking on stories that could involve breaking a country’s rules or laws, or violating individual privacy:

- Is this story in the public interest?

- Is it a story of real importance?

- Is there no other way of getting the information?

- Will I be putting anyone at risk? (And, if so, am I prepared to pay their potential legal costs, or the cost of getting them out of the country?)

- If I am paying a criminal, am I encouraging crime – and what will the criminal do with the money?

- Has anyone working with me — especially any young journalist — been in any way pressured to take part in breaking normal rules or laws? “We should be alert to the fact that many young journalists want to make a name for themselves, and might put themselves up to doing things that really they shouldn’t,” Byrne notes.

- To what extent will we be transparent afterwards about how we gained the information?

“Obviously, in the case of the poisoning and attempted murder of Navalny, that certainly answers the first two points (public interest and importance),” Byrne says. “And it is important that we consider methods like [illicit data markets] only if the story really is important, and not just one that would make us famous. Using them to find out something about the British royal family would not be justified.”

Byrne adds that the amount of money paid for black market data also could make an ethical difference, as “a large sum of money” paid to a criminal is more likely to be repurposed to commit additional crimes.

Grozev said the data purchases on the Navalny case were low-cost, and that paid-for online datasets often cost as little as $12. He stressed that Bellingcat only resorts to black market data when state actors are believed to be involved with major wrongdoing — and that it is necessary when investigating security services simply because they are experts at covering their tracks.

These are the ethical guidelines that govern Bellingcat’s use of confidential and black market data. Image: Screenshot

Grozev says another advantage of collaborating with outlets like The Insider and Der Spiegel on the most serious stories is that “all of these hard decisions are made on the basis of consensus.”

“That means the media outlet with the highest ethical standards has the veto right over decisions,” he explains.

And he warns that illicit data markets should not be used based on a hunch, but only after a strong hypothesis has already emerged from evidence based on open source or traditional reporting.

On the other hand, Grozev says false identities used by spies are fair game, ethically and legally, when considering privacy invasions with confidential data. The reason: “Because they’re fake people!”

Additional Reading

The Forensic Methods Reporters Are Using to Reveal Attacks by Security Forces

My Favorite Tools with Russia’s Roman Anin

What Journalists Can Learn from Navalny’s Investigative Team in Russia

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.