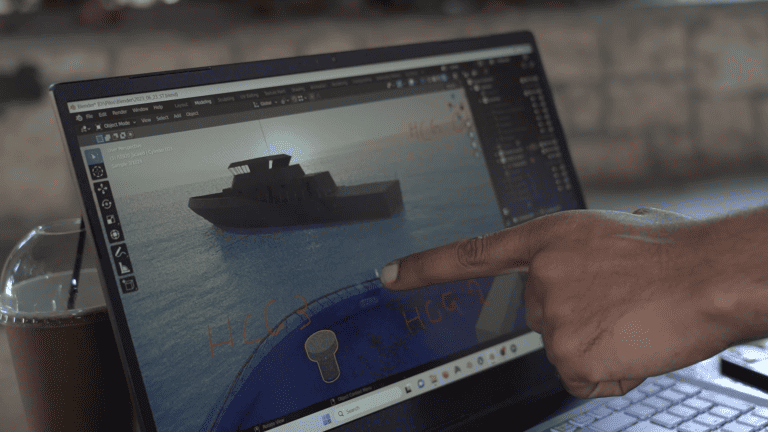

A survivor points to the place they say a rope was tied onto the Adriana, shortly before it sank in the Mediterranean in June 2023. Image: Courtesy of Forensis

How They Did It: Investigating the Pylos Shipwreck

Read this article in

In the early hours of the morning of June 14, 2023, a small fishing trawler carrying hundreds of migrants sank off the coast of Pylos, Greece. Roughly 600 people died in what has become one of the deadliest migrant shipwrecks in recent years.

The Hellenic Coast Guard — responsible for search and rescue operations in Greek waters — was strongly criticized for its handling of the operation. It denied responsibility for the incident, claiming that migrants onboard rejected their offers of assistance and that the boat tipped over seemingly from a mass movement of people to one side of the overcrowded vessel.

But the results of a cross-border collaboration between investigative journalists and researchers cast significant doubt on the officials’ story.

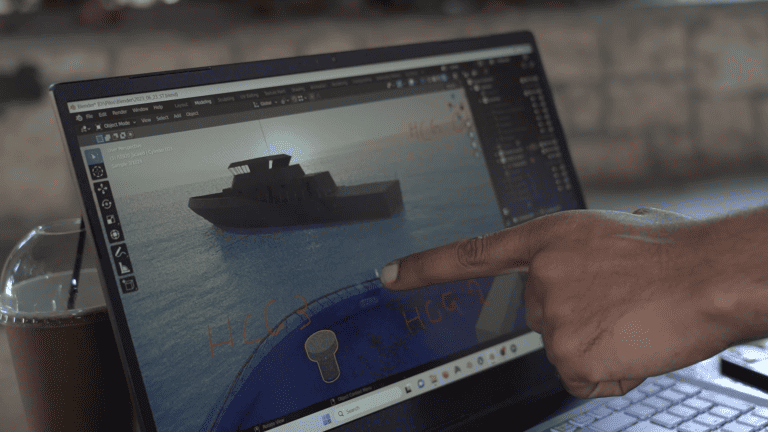

The Berlin-based Forensis research group, the Guardian, Greek investigative unit Solomon, and German public broadcaster ARD used 3D modeling, satellite imagery, vessel tracking data, and official sources to reconstruct the trawler’s final hours.

They uncovered evidence to suggest that the Adriana sank as a direct result of attempts to tow the vessel by the coast guard — a charge that the force has consistently denied. Their investigation also revealed the coast guard’s failure to activate its cameras when the boat was in difficulty, inconsistencies in its logs, apparent attempts to doctor survivors’ testimony, and missed opportunities for an earlier rescue.

Combining Two Skill Sets

Forensis is a research group that uses cutting-edge techniques to investigate human rights abuses. The team, composed mostly of architects, brought their expertise in spatial analysis and digital reconstruction to the Pylos shipwreck investigation.

But collaboration was key. “There were parts of the research we couldn’t have done,” says Stefanos Levidis, a lead researcher on the Forensis team. “Getting access to survivors and sources within the coast guard, the ability to dig into state archives and look for traces of funding, or examining operational documents: this is the bread and butter of investigative journalists.”

Journalists from Solomon combed through official documents, while the Guardian’s team leveraged an extensive source base within the Greek state to gain access to exclusive records. Together with journalists from ARD, they also interviewed survivors of the shipwreck.

“Each party brought a different set of expertise to the project,” Levidis explains. “None overweighed the other. It was a productive and equal collaboration.”

Using 3D Models While Interviewing Survivors

Situated testimony is an interviewing technique developed by Forensic Architecture, Forensis’ sister agency. Witnesses are invited to recount their experience of a traumatic event using 3D models of the scene as a reference.

“We find that working with spatial testimony and spatial tools helps witnesses unlock certain parts of their own memory which would otherwise be obscured or lost to trauma,” Levidis says.

Forensis built a to-scale 3D virtual model of the Adriana and invited survivors to use it to help describe the moments just before and during its sinking.

“For us, it made what happened to them a lot more real. They could pinpoint exactly where they sat, where others were sitting around them, and how the boat moved. It brought home how horrific it all was,” Katy Fallon, a freelance journalist on the Guardian team who observed this interview method for the first time.

The reporting team supplemented these guided testimonials with traditional interviews. But accessing the survivors, who were held in a heavily secured camp, was challenging. As well as being traumatized, they were hesitant to talk to journalists for fear of reprisal.

Building trust was key. ARD’s Sulaiman Tadmory, a native Arabic speaker, was able to quickly establish rapport with Syrian and Egyptian survivors — and held interviews outside of the crowded camp to ensure the migrants felt safe and comfortable.

“We were perceived by the security surrounding the camp as family of the survivors — we could go where other journalists couldn’t go,” notes Armin Ghassim, an ARD colleague who also worked on the investigation.

In all, the team spoke to more than 20 survivors. Multiple corroborating testimonies describe attempts by the coast guard’s ship to tow their vessel, likely into Italian waters. The investigation “strongly suggests” that one of these attempts caused the Adriana to lurch violently, ultimately resulting in its capsizing.

Mapping the Adriana’s Final Hours

To map a detailed chronology of the Adriana’s movements, the consortium used official reports from the Hellenic Coast Guard and EU border agency Frontex, deck logs from the coast guard vessel and nearby tankers, aerial photographs, marine traffic data (AIS), and satellite imagery. The reconstruction revealed several inconsistencies in the coast guard’s logbook. “The towing is the tip of the iceberg,” says Giorgos Christides, a Greece-based journalist who worked on the Guardian team for this investigation. “What we found was a laundry list of things that had gone horribly wrong.”

For Corina Petridi and Stavros Malichudis of Solomon, their efforts involved a lot of desk research. To them, one document in particular stood out. It included a series of recommendations issued by Frontex, which state: “If feasible, all actions taken by Frontex assets or Frontex co-financed assets … should be documented by video consistently.” Greece’s coast guard receives 90% of its funding from the EU border agency.

“The Frontex document we included in our piece is very important because it shows that the coast guard should have had its cameras on,” Malichudis says. “We are talking about around 600 dead people. It’s about accountability. If the cameras were on we wouldn’t have needed to do this investigation. It would have meant that people knew what happened.”

Extensive Source Network

The team was able to reveal several damning shortcomings of the Greek authorities by tapping into an extensive network of government sources.

One source revealed that the coast guard had nearby vessels that were not dispatched prior to the Adriana’s sinking. The investigation also uncovered evidence that the authorities had been notified that the trawler’s seaworthiness was at risk well before it sank — documented by alert emails received by the emergency hotline Alarm Phone and aerial footage.

By accessing the survivors’ testimony given to the Greek authorities, the investigation also points to the likelihood that some of the transcripts had been doctored; several survivors repeated the same accounts word for word — and, contrary to the testimony collected by the team of journalists, none mentioned the towing.

These conclusions fit a previously documented pattern. Solomon’s Petridi and Malichudis have extensively covered migration issues in Greece. In previous investigations, they have repeatedly seen evidence of authorities doctoring migrants’ testimony in this way.

The combination of access to classified official documents, and in-depth survivor testimonials allowed the team to look past the official account and get at the truth.

“It’s a big puzzle,” says Christides. “When you put it all together, it points to the conclusion that what Greece wanted to do was let time go by and get this problem out of its hands,” he continued. “I don’t think there was ever any serious intention to do a search and rescue operation. This was a preventable tragedy.”

Prior to publication, the team sent a detailed questionnaire to the Greek authorities about its findings, including the evidence that suggested the coast guard could have doctored or manufactured victims’ statements. The government refused to comment, other than saying that its own internal investigation into the sinking was still underway. After the story came out, the authorities still did not publicly respond.

Working Together

“We published the story not even one month after it happened. We would not have been able to pull something off like this on our own. Everyone was depending on each other, and everyone had something important to add,” ARD’s Ghassim points out. “Collaborating was necessary, we couldn’t have done this quality reporting so quickly on our own.”

Working in such a big group not only brought a variety of different skill sets together, but it also increased the reach of the story to multiple countries. The investigation was published on each member’s own platform, and each outlet was given the autonomy to highlight the details they thought would resonate with their respective audiences.

Several of the consortium’s members pointed out that the collaborative aspect helped to mitigate some of the adverse mental health effects of working on such difficult subject matter.

“I appreciated doing this story with lots of people. When you do these stories alone, you ingest a lot of the horror alone,” says the Guardian’s Fallon.

Impact

Members of the team at the award ceremony for the Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism 2023. Image: Courtesy of the prize, copyright European Union 2023

The investigation won the 2023 Daphne Caruana Galizia Prize for Journalism and was hailed by the president of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, at the awards ceremony.

“The winners meticulously researched the precise circumstances, spoke to eyewitnesses and survivors, analyzed data, and showed that these people wouldn’t have died if European authorities had acted differently,” says Juliane Hielscher, representative of the jury that selected the Pylos story from over 250 investigations.

On September 13, 2023, 40 survivors of the shipwreck filed a criminal complaint with the Maritime Court of Piraeus in Greece. Forensis has committed to assisting their legal team by sharing their findings with them.

Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International also launched independent human rights investigations about the incident, arriving at similar conclusions.

The team, however, recognizes the further work necessary to improve the conditions at Europe’s borders. “I think of this as one of many cases, maybe the biggest of many, but just part of the constellation of death and violence at the European border,” Levidis says. “The only way to say that we have justice is for this violence to stop.”

Isabella Crispino is New York-based journalist and researcher. She has worked with investigative outlets Daraj in Beirut and Inkyfada in Tunis, and is a graduate of Oxford University. Currently, she is pursuing a Master of International Affairs joint between Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and Sciences Po, specializing in human rights.

Isabella Crispino is New York-based journalist and researcher. She has worked with investigative outlets Daraj in Beirut and Inkyfada in Tunis, and is a graduate of Oxford University. Currently, she is pursuing a Master of International Affairs joint between Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and Sciences Po, specializing in human rights.