Investigating Human Trafficking, an Evil Hidden in Plain Sight

Read this article in

Editor’s Note: For the next several months, GIJN is running a series drawn from our upcoming Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime, which will debut in full in November at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. This section, which focuses on Investigating Human Trafficking, was written by Martha Mendoza, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and part of the Associated Press team that exposed the use of slave labor in the Thai seafood industry. For those interested in more tips and tools on covering human trafficking, check out this GIJN webinar hosted by Mendoza.

Human trafficking is a persistent and pervasive crime around the world, and a critical and impactful area for journalists to investigate. All too often modern slavery is an evil hidden in plain sight, in a neighborhood massage parlor or aboard a fishing boat moored at a local dock. There are two basic categories of human trafficking: sexual exploitation, which makes up about half of human trafficking, and labor abuse. On any given day, there are an estimated 40 million victims of modern slavery, mostly women but also men and children, according to United Nations data. The perpetrators, so-called traffickers and slave masters, collectively gain some $150 billion a year in illicit profits, according to the International Labour Organization.

Investigating human trafficking can be fraught. Victims face grave danger for speaking to journalists. They are traumatized, often terrified of their captors, and have been specifically warned not to ask for help from anyone, let alone a reporter. Their lives can be at risk when they speak to journalists, so approach this type of work with great care. The perpetrators are criminals willing to exploit other human beings. They can be ruthless, and want to protect their own interests.

Who to Speak With

With that in mind, there are some great sources to help journalists investigate human trafficking, starting with the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working to end modern day slavery. Global organizations such as the International Organization for Migration, Minderoo (Walk Free) Foundation, Polaris Project, and Catholic Charities have in-country representatives who are often able to provide a great overview of particular issues in specific regions.

Some, like International Justice Mission, work closely with law enforcement to identify, arrest, and prosecute perpetrators. Others, like Issara Institute, work with migrant community groups and businesses to conduct audits and give workers a voice. And there are groups like Free the Slaves that aim to change the conditions that allow modern slavery to exist. Many of the NGOs are faith-based, some are government-run, and some are topic or country focused.

The first step in investigating human trafficking is to talk to as many organizations in the area as possible — at least a dozen. They can make introductions to formerly enslaved survivors, point out prior prosecutions, and identify specific areas where journalists are likely to find human trafficking.

For example, in Malaysia, rubber glove factories have, for years, been cited for labor abuse among the migrant workers who often pay illegal recruitment fees to work there. The sex trade has flourished in Middle East cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi for generations, with foreign women brought into the country on the pretext of performing domestic work and forced to work in the sex industry. Slavery has also been well documented in commercial fishing, where the work usually takes place far offshore, without oversight, by migrant workers who are vulnerable to becoming trapped and abused.

Beyond the human sources, many governments and the United Nations publish annual reports that provide specific, on-the-ground information about modern day slavery. These include: the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, the US State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report, and the European Union’s Together Against Trafficking in Human Beings. The US Department of Labor also publishes an annual List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, specifying 155 suspect goods — such as textiles from Cambodia, soccer balls from India, or coal from Ukraine — where abuse may occur in the supply chain.

A lot of accountability work for journalists covering human trafficking comes from following the money and supply chains. First-hand observation is the best way to do this. If possible, observe, look at labels and brands, follow the products, or the victims, to find the people profiting from their abuse. For labor supply chains, trade data allows journalists to track shipments from specific factories to buyers in another country.

Another great source for following the money are corporate records, which show annual revenues, business partners, and company relationships. Court records can also be helpful, identifying details about people arrested for human trafficking and their ties to other organizations.

Case Studies

The Guardian: UK Sourced PPE from Factories Secretly Using North Korean Slave Labour

As the global COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, demand for medical masks, gloves, swabs, and gowns soared, overwhelming factories in China, where most of those items were typically manufactured. In November, 2020, the Guardian published an exclusive investigation that found the UK government was buying personal protective equipment from Chinese companies that were secretly staffing their factories with North Korean forced labor. The three-month investigation found that enslaved people, mostly women, were under constant surveillance, unable to leave, and spending up to 18 hours a day at work. The North Korean regime routinely sends its citizens to foreign jobs and then collects their salaries, a practice the UN and US have declared a crime. In response, the UK government vowed to be more transparent about government contracts, saying it deplored labor abuse in these supply chains and was working to end it.

CNN: Troubled Waters: Inside the Child Slavery Trade

Children are bought for about $250. They spend their days untangling fishing nets. And they’re never paid. In February 2019 a report from CNN exposed what local news organizations and advocates have been saying for years: some 20,000 African children are enslaved on Ghana’s Lake Volta. Their parents sell them to fishermen, or swap them for a cow. The work is incredibly dangerous. To peel back the curtain of this practice, CNN journalists worked with a local advocate who rescues, shelters, and educates formerly enslaved children. In a visually engaging piece, CNN followed children as they worked, and interviewed their families, captors, and rescuers. The work followed Joy News’ 2017 Slaves of the Volta, a deeply sourced documentary that also told the stories of formerly enslaved children and how their lives were impacted.

Associated Press: Seafood From Slaves

Over the course of 18 months, Associated Press journalists found men held in cages, and tracked the seafood they caught and processed for US supermarkets and pet foods. The work was awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service and, more importantly, led to the freedom of more than 2,000 men. There were prosecutions, financial seizures, and an industry-wide commitment to improve labor supply chains. The investigation came after a series of articles that told anecdotal stories of migrant fishermen in the Thai seafood sector who described being enslaved. Although their stories were disturbing, they hadn’t made much impact. The AP investigation identified people who were currently enslaved, and then held the slave masters, and those doing business with them, accountable. The work was the first of dozens of supply chain investigations that have exposed labor abuse around the world, prompting sanctions and bans.

Tips and Tools

For reporters who want to delve into this subject:

- Learn about trauma-informed interviewing before reporting on survivors of sexual or labor exploitation. The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma has many resources, as well as the Global Investigative Journalism Network. Also ask the NGOs about how best to engage and protect sources.

- Trade data aggregators Panjiva and Importgenius provide import-export records that allow journalists to track an item from the factory where it was made to the buyer in another country. It can also include brands of items made in a specific factory.

- OpenCorporates is the largest open database of companies in the world, with about 190 million corporations from 130 jurisdictions. It takes a lot of digging, but journalists can track corporate board officers, annual reports, articles of organization and more, tying people and money from one company to the next.

- Use networks like GIJN or reporting initiatives like one recently announced by the Journalism Fund to find collaborators. Covering human trafficking is incredibly difficult, but working with journalists in origin and receiving countries makes the work much more feasible.

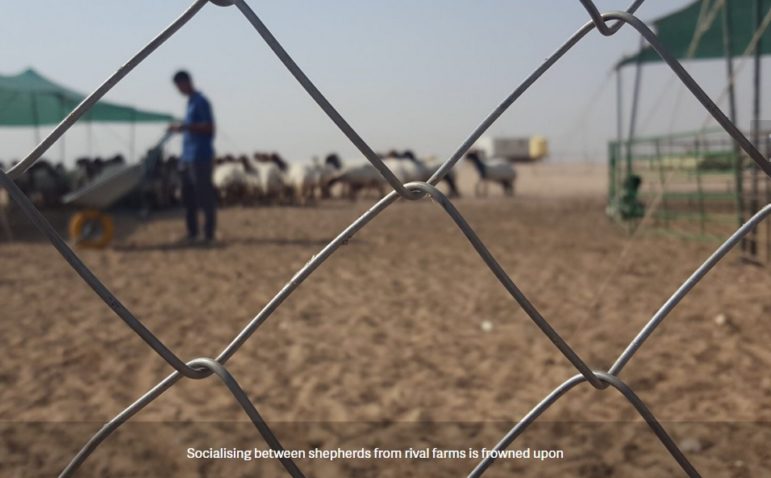

- Re-examine societal norms: sometimes a common practice is actually modern slavery. For example, the kafala or sponsorship system in the Middle East often results in debt bondage for the Asian workers sent there for temporary jobs; the restavek children in Haiti sent by their parents to work as domestic servants are victims of a form of child slavery; and, in the US, AP identified a visa scheme in the Hawaiian fishing fleet that allows foreign workers to work on boats without any protection from American labor laws.

Be Mindful

Investigative journalists are dedicated to giving voice to the voiceless and holding those in power accountable. Investigating and exposing human trafficking accomplishes both. Indeed, there are few areas of reporting that can bring such immediate, positive impacts to an individual’s situation, and long-term improvements to an exploitative business practice.

So, be careful, be persistent, and always keep the safety of victims in mind. In 2016, colleagues of mine at the AP went back and interviewed men who had been freed as a result of the Seafood From Slaves investigation. Some suffered trauma and night terrors, some struggled with shame or returned to abusive situations, but others found decent work, were opening businesses, starting families, even taking their traffickers to jail. Many said their pain has lessened with the passage of time, and they’re grateful for their freedom. “Still, they are thankful to be home, living as free men,” the AP reported. “They are slaves no more.”

Additional Resources

GIJN Video: Exposing Human Trafficking with Martha Mendoza

GIJN Resource Center: Human Trafficking, Best Practices for Reporters

How They Did It: Investigating the Trafficking of Girls from Nepal to the Gulf

Martha Mendoza is a Pulitzer prize-winning Associated Press reporter. She currently writes breaking news, enterprise, and investigative stories from Silicon Valley, in California. She was part of a team that exposed forced labor in the fishing industry in Southeast Asia in 2015, an exposé which helped to free 2,000 slaves.

Martha Mendoza is a Pulitzer prize-winning Associated Press reporter. She currently writes breaking news, enterprise, and investigative stories from Silicon Valley, in California. She was part of a team that exposed forced labor in the fishing industry in Southeast Asia in 2015, an exposé which helped to free 2,000 slaves.