Image: Screenshot, Forbidden Stories

Investigating Organized Crime in the Amazon: The Bruno and Dom Project

Read this article in

Image: Screenshot, Forbidden Stories

The first scene of The Bruno and Dom Project trailer shows the moment when members of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of Vale do Javari find British journalist Dom Phillips’ press card buried in mud on the bank of the Itaquaí river in Atalaia do Norte, in the Brazilian state of Amazonas.

The image symbolizes the efforts of the more than 50 journalists involved in the project to honor the legacy of the journalist and Brazilian Indigenous affairs expert Bruno Pereira by exposing the illegal activities in this area along the borders of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, where the two men were murdered on June 5, 2022.

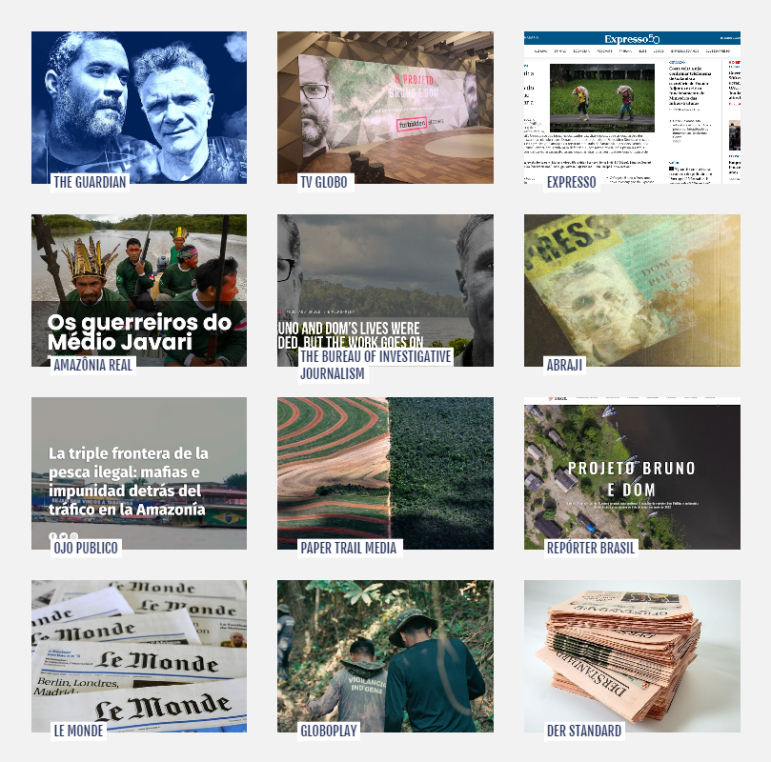

The project, led by French organization Forbidden Stories, went live on June 1, 2023 and included 16 news outlets in 10 countries: Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo (Abraji), Amazônia Real, Folha de S. Paulo, Repórter Brasil, and TV Globo from Brazil; Ojo Público from Peru; Der Standard from Austria; Expresso from Portugal; Le Monde from France; NRC from the Netherlands; the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP); Paper Trail Media from Germany; Tamedia from Switzerland; and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Guardian from the United Kingdom.

Over the past year, journalists from these news outlets have investigated the context and circumstances that culminated in the murders of Phillips and Pereira. These include the strengthening of organized crime groups, which are active in various illegal activities such as fishing, mining, and deforestation in the Vale do Javari Indigenous land. When he was killed, Phillips was accompanying Pereira, a recognized expert dedicated to protecting isolated Indigenous people. Phillips was conducting research for a book he was writing on sustainable development in the Amazon.

Each news outlet produced and published original content based on the investigations carried out by reporters in the field and on the news desk, and shared among the project partners. Many also republished feature stories produced by their colleagues, including translating them into other languages, as Amazônia Real and Ojo Público did.

Laurent Richard, founder and executive director of Forbidden Stories, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) the project took shape soon after it was confirmed that Phillips and Pereira had been killed, 10 days after they disappeared. The organization is dedicated to continuing the work of murdered journalists, he said, because these murders always happen when journalists are investigating important stories.

“Our mission is to make sure that the story will not disappear with the journalist, so we can really do our job to inform public opinion, to let them know: what was the story that the journalist has been killed for? What was the story people tried to silence?” he said.

“In the very long term, we really want to dissuade the killers and the people who are harming journalists so they don’t do that, because it’s really counterproductive,” Richard said.

Filling in the Gaps

The scene that opens the project’s trailer was captured by the film crew of the documentary “Vale dos Isolados: the Murder of Bruno and Dom,” directed by journalist Sônia Bridi, of TV Globo, and available on the Globoplay platform. Bridi said that this moment was recorded in October 2022, four months after the murders.

Armed with a metal detector, members of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of Vale do Javari Surveillance Team (EVU) also found the identity cards of Phillips and Pereira, the journalist’s notebooks, and the Indigenous expert’s cell phone, which has the last photos of the two, taken moments before they were murdered.

The metal detector was lent by the documentary team, at the request of the EVU members, Bridi said. They wanted to find Pereira’s gun, as they feared it would be found by criminals in the region and used to kill someone.

“We asked the forensics of the Federal Police what the right detector would be. We brought it and delivered it to them. And we went along because we knew something could happen,” Bridi said.

The gun was not found, but the rescue of the journalist and the Indigenous expert’s personal belongings was a very strong moment for all present, she said.

When they went to the area where Dom Phillips had disappeared, reporters found his UK press card and other personal belongings. Image: Screenshot, Forbidden Stories

“I am also a journalist who works in the Amazon region, I had met Dom there. When I saw Dom’s press credentials [in the mud], the crime became so graphic, the murder of a journalist…” she said.

“The entire moment was very sad. Everyone was there looking. Someone said, ‘look, there’s something here,’ and there was silence. It was a sad and respectful moment. But, for me, the saddest moment was when they found the notebooks,” Bridi said.

Eduardo Nunomura, special projects editor at Amazônia Real, said that he believes this is the “big scoop” of The Bruno and Dom Project.

“Journalism was capable of doing what the police did not do,” said Nunomura, who coordinated Amazônia Real’s participation in the project. “They didn’t find [Pereira’s] cell phone, the Indigenous people did… The Indigenous people were the ones who found it because they got a metal detector.”

Despite the discovery of the documentary team, Nunomura said that from the very beginning of the project, the journalists involved realized that it was not about obtaining a scoop. It was, in fact, about continuing Phillips’ work of telling the story of the problems of the Amazon region and possible solutions.

“All the coverage that he [Phillips] did of mining on Indigenous lands, for example, he was always thinking the following — there is a problem, but how are we going to solve this problem? He said that we can’t look at the miners as the big bastard of the story. They have families, too. We need to understand, take a broader look, why this economic plot, this destructive logic, has taken hold in the Amazon,” Nunomura said. “We must not lose sight of the fact that a large part of the people who are there are not from there. They came from other regions and don’t have a relationship of belonging to the Amazon region, like the Indigenous populations do. Even the river dwellers, who are fishermen, have a predatory relationship with the Amazon. And this is a question we have to discuss,” he added.

‘You are Seeking Out Your Own Death’

Amazônia Real, a Brazilian news outlet that is a reference point in the coverage of the Amazon region, stood out in the heated coverage of the murders of Pereira and Phillips because of its network of contacts among the Indigenous people, who led the search after their disappearance of the pair.

For The Bruno and Dom Project, they produced three special reports: The Middle Javari River Warriors, by Elaíze Farias with photos by Bruno Kelly; The Hunger for Gold in the Madeira River, by Francisco Costa with photos by Bruno Kelly; and A BR-319 Highway in the Middle of the Road, written by Leanderson Lima with photos by Alberto César Araújo.

When invited to participate in the Bruno and Dom Project, Amazônia Real also suggested calling the Peruvian news outlet Ojo Público, which has also been covering the region where Pereira and Phillips were murdered.

“For us, it was very important [to participate in this project] because this area… borders the Peruvian Yavari Valley. In recent years, Peru has seen an explosion of illegal coca leaf crops in this area. But also the presence of armed groups linked to drug trafficking and the invasion of land for coca leaf and other supplies, leaving in their wake many threats to the Indigenous peoples who inhabit this part of the border,” he said.

The feature story produced by Ojo Público for the project deals with the “triple frontier of illegal fishing” in the region: How fish taken illegally from Indigenous lands in Brazil crosses the borders of Peru and Colombia and enters the formal market. As the story points out, Brazilian and Peruvian authorities maintain that drug trafficking is behind the financing of illegal fishing.

Ojo Público editor Nelly Luna said that reporter Rodrigo Pedroso and photographer Alex Rufino, who did the story for Ojo Público, were the target of intimidation and threats several times while in the field — evidence that the insecurity and risks for journalists working in the region have changed little since the murder of Phillips and Pereira.

“Our idea was to reconstruct the route of the illegally extracted fish that ends up being laundered in the formal market. And when [the reporter] arrived at one of the containers of these companies that have cold storage rooms in Leticia [Colombia] to ask if they could show him the fish, how it arrived, someone told him directly that he was seeking out his own death,” Luna said.

According to her, the professionals were working under a security protocol and soon after this episode it was decided that it was necessary for them to end their trip and return to Manaus, the capital of the state of Amazonas in Brazil, where they were based.

Collaborative Investigations

Stories produced as part of The Dom and Bruno Project by Forbidden Stories. Image: Screenshot, Forbidden Stories

Many of the news outlets involved in the Bruno and Dom Project sent reporters to the Amazon to carry out investigations on the ground. The field and newsroom findings were shared and discussed in virtual meetings held periodically over the past year.

“We shared travel dates, investigative findings, interviews… All the raw material was shared during this time with the idea that each news outlet could take what the other was also covering, interviewing, collecting data, and of course, giving proper credit in the stories. But, in the end, each news outlet was free to make their own story based on the shared content,” Luna said.

Richard recalled that this willingness to do collaborative journalism is not always something natural for reporters used to competing for exclusivity.

“We need people who really believe in collaborative journalism, which is not that easy. You have to share your ongoing work with your partners. Sometimes, they are your competitors from way before and they are going to be your competitors tomorrow, but you’ll have to work closely with all journalists,” he said.

Bridi said she believes that “collaborative journalism is the future of journalism.” In addition to the documentary, made by Globoplay, she also produced for TV Globo an investigation into illegal logging from Indigenous lands in an area of the Amazon in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso.

“We all like a scoop. But journalism is an expensive business that requires time and money. So when you join forces, different views and approaches, you have a much richer process. And an immensely richer result,” she said.

Justice and Impact

Three local fishermen are in jail for the murders of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips. Two confessed to the crime days after the disappearance of the Indigenous expert and the journalist, according to police, and led them to the bodies.

Another man, Ruben Villar, known as “Colombia,” has been singled out as the crime’s mastermind. According to police, Villar is the leader of a criminal organization that finances illegal fishing. He was indicted for the murders of Pereira and Phillips in May, according to a story by TV Globo’s Fantástico. Another suspect — Jânio Freitas de Souza — has also been indicted for his participation in the crime.

On May 8, during a hearing to decide whether they should go to trial for the murders, two of the fishermen accused of being involved in the crime — Amarildo da Costa de Oliveira and Jefferson da Silva Lima — presented a new version of what happened, saying they shot Pereira and Phillips in “self-defense.”

The Observatory of Isolated Indigenous Peoples (OPI) classified as “fanciful” the new version presented by the accused and rejected what it considers an attempt “to tarnish the memory [of the victims] as a defense strategy.”

Sônia Bridi said she hopes that her documentary will help “to form a shield against this attempt at the moral assassination of the victims” by those accused of the crime.

“The second thing is to keep this memory alive. Brazil has such a large and rapid production of tragedies and crimes that one buries the memory of the other. But we have to revive the memory of this crime. It cannot be forgotten. I would also like people to understand what is at stake there, to understand why Bruno died, why Dom died, what they were doing there, what and who they were defending,” she said.

Nelly Luna said she hopes the Bruno and Dom Project stories will help to promote “a greater awareness of the state of neglect on this side of the border” and call the attention of the authorities in Brazil and Peru, as well as the populations of the two countries, to what is happening in that region.

“While the Amazon is becoming a terrifying scene of organized crime, the murder of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira should make us reflect on all the chains of responsibility that exist around this,” Luna said.

“Organized crime is a violent actor, but we must ask ourselves where these products that are illegally extracted end up. There is also a market responsibility in the way in which these products are being laundered, because part of the fish, it is true, ends up feeding a local population, but the other part ends up in luxury restaurants, they even end up in export chains,” she said.

This story was originally published by the LatAm Journalism Review at the Knight Center at the University of Texas at Austin and is republished with permission. It has been edited for style. You can see the original here, plus versions in Spanish and Portuguese.

Additional Resources

My Favorite Tools: Geo-Journalist Gustavo Faleiros

Supercharge your Environmental Investigative Stories with Data and Visuals

Investigating Rainforest Destruction: Finding Illegal Airstrips Using Machine Learning

Carolina de Assis is a Brazilian journalist and researcher who lives in Juiz de Fora, Brazil. She holds a master’s degree in Women’s and Gender Studies from the GEMMA Programme – Università di Bologna (Italy) / Universiteit Utrecht (The Netherlands) and has worked as an editor at Gênero e Número, a Brazilian digital magazine focused on data journalism and gender issues.

Carolina de Assis is a Brazilian journalist and researcher who lives in Juiz de Fora, Brazil. She holds a master’s degree in Women’s and Gender Studies from the GEMMA Programme – Università di Bologna (Italy) / Universiteit Utrecht (The Netherlands) and has worked as an editor at Gênero e Número, a Brazilian digital magazine focused on data journalism and gender issues.