Image: Screenshot

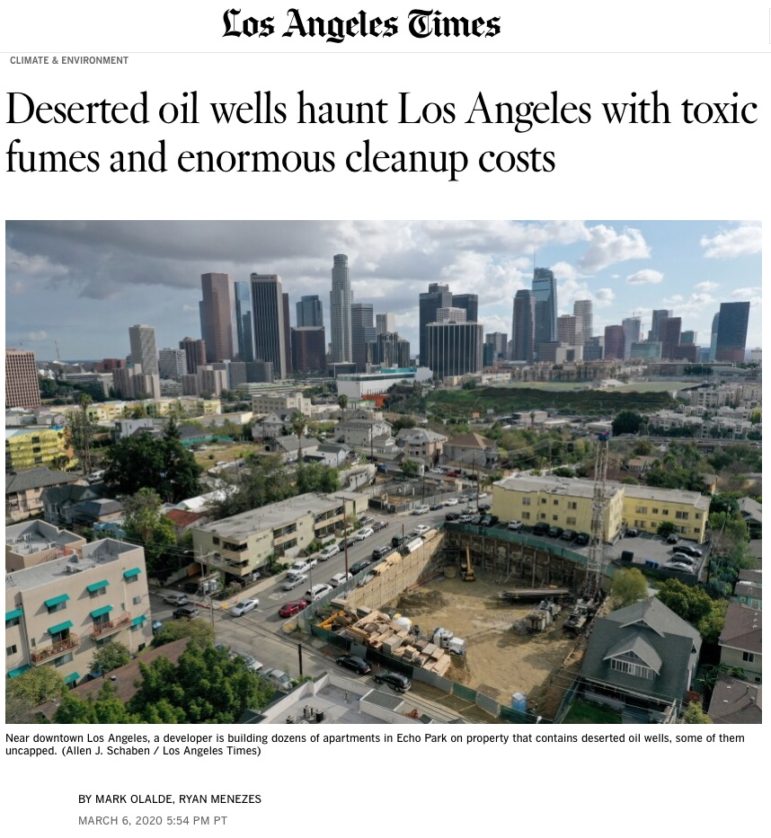

Investigating the ‘Toxic Legacy’ of Abandoned Oil Wells

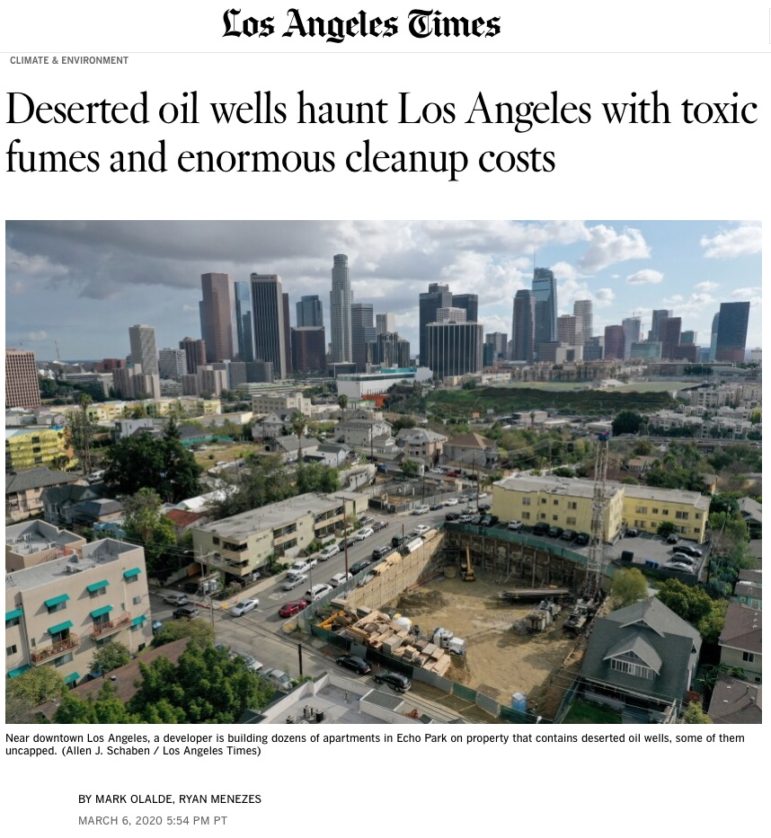

A collaborative investigation by GIJN member Center for Public Integrity and the Los Angeles Times saw two reporters analyze government data on dry oil wells in California, revealing serious issues for surrounding low-income communities. The coverage, by Mark Olalde and Ryan Menezes, won second place in the Kevin Carmody Award for Outstanding Investigative Reporting, in the large market section, at the Society of Environmental Journalists’ 20th annual awards.

Judges said the project “revealed that the 35,000 dry oil wells across California require a massive cleanup… Among the risks posed by these wells sitting in dense neighborhoods are the leak of noxious fumes as well as the risk that at any point the wells could prompt potentially catastrophic blowouts and explosions.”

This Q+A was originally published by the Society of Environmental Journalists. It is republished here with permission, with additional advice from Olalde for journalists worldwide looking to conduct similar investigations.

SEJournal: How did you get your winning story idea?

Mark Olalde: On most mornings, I’d wander into an editor’s office with a cup of coffee for a meandering chat about journalism and the environment. One day, he asked if I had any investigative ideas in California. Nope. So, I picked a topic that interested me — oil — and took a few weeks to check production statistics, call regulators, chat with activists, and read clips — anything to spark me. Between the data and the conversations, the reality of the state’s oil industry pretty quickly came into focus.

SEJ: What was the biggest challenge in reporting the pieces and how did you solve that challenge?

MO: The strength and the difficulty of this piece were both centered on its massive data work, which led to novel findings. We successfully tackled this challenge with a smart organization of our team and delineation of responsibilities. On one side, I was an expert in the extractive industry, and on the other, Los Angeles Times reporter Ryan Menezes was an expert on all things data. We spent time at the outset identifying what data resources existed, what they told us, how they could be joined, and how we could access them. Then, we combined as much government and industry data as we could — crashing a computer in the process — so we could begin lobbing queries at it that arose from our on-the-ground reporting.

SEJ: What most surprised you about your findings?

MO: The regulatory side of the government was asleep at the wheel in terms of protecting taxpayers from future environmental cleanup costs of the oil and gas industry. While Ryan’s data work was very impressive, I didn’t see a real reason the government hadn’t attempted something similar years ago and was slow to make their findings publicly available when they did begin doing more data analyses recently.

SEJ: How did you decide to tell the series and why?

MO: We decided that the people whose lives were impacted by living near this unplugged oil and gas extractive infrastructure needed to be heard early and often in the series, so we did our best to highlight them, including through the work of the Los Angeles Times’ amazing photography department.

SEJ: Does the issue covered in your series have a disproportionate impact on people of low income, or people with a particular ethnic or racial background? What efforts, if any, did you make to include perspectives of people who may feel that journalists have left them out of public conversation over the years?

MO: Combining data from the census and California oil regulators, we analyzed the demographics of people living close enough to oil and gas wells that their health is likely impacted. We also spent significant time in the field and made sure to have the right people in the room to be able to conduct interviews in Spanish, so we could hear the voices of Latinos who are often most directly affected by environmental health issues in California.

SEJ: What would you do differently now, if anything, in reporting or telling the stories and why?

MO: This is one of those series that I look back on proudly. But perhaps we could’ve broken things down even further into more and smaller stories to help people better understand the complex data findings.

SEJ: What lessons have you learned from your project?

MO: Traditional print reporters need to make specialty teams — data, visuals, developers — partners on projects. Do that and a project’s possibilities are endless.

SEJ: What practical advice would you give to other reporters pursuing similar projects, including any specific techniques or tools you used and could tell us more about?

MO: Go further than what environmentalists say. If they’re correct, data will bear that out.

SEJ: Could you characterize the resources that went into producing your prize-winning reporting? Did you receive any grants or fellowships to support it?

MO: This series took about six months to complete, with the two lead reporters putting half or more of their time toward it.

GIJN: What advice do you have for journalists investigating the oil industry outside of the US?

MO: In the face of climate change, the global oil and gas industry needs an investigative spotlight now more than ever. Whichever way you slice it, the hydrocarbon business is massively funded by taxpayers who then suffer downstream public health and environmental consequences. A 2021 working paper from the International Monetary Fund, for example, put annual fossil fuel subsidies somewhere in the ballpark of US$6 trillion. With so much cash floating around, there are plenty of stories to write about money disappearing from public coffers or questionable tenders and permits.

The first step is identifying what types of data exist — for example, barrels of oil produced monthly or amounts of money held in cleanup funds — and what agency holds the data in order for you to request it. In South Africa, for instance, the country has a public records law called the Promotion of Access to Information Act that allows you to ask for public documents and data. A court ruling there in 2014 even allowed this transparency law to be applied to businesses — not only government entities — although that is a rarity globally.

Unfortunately, in many countries, the reality is that government data is messy or that transparency laws are not followed. Thankfully, companies often keep detailed records about things like oil and gas production because money is involved. So, even if a government should keep the records, it often works best to query companies, especially if they’re headquartered in jurisdictions with progressive transparency laws.

GIJN: What kind of documents and sources should journalists look for?

What do the companies’ annual reports say? What are they telling their business partners via shareholder meetings and investor conference calls? What permits were they supposed to get from your government? Who did they hire as their local contractors, legal representatives, or partners? What do their required financial reports say if they are listed on the London, New York, Johannesburg, Australian, or other stock exchanges? Additionally, if you’re reporting from developing nations and need data on extractive industries, consider contacting international NGOs like Publish What You Pay or Global Witness, that might already be aggregating some useful data on the subject or might have experience conducting research in your country.

Even if data is hard to come by, there are still plenty of entry points into oil and gas stories. If residents living near extractive infrastructure complain about health disparities, perhaps you can place air monitors or map community health outcomes, and bring that information to doctors to analyze. If there’s a plan to open a new oilfield, perhaps you can investigate which government officials signed off on what permits, how they’ll benefit from the deal, what royalties and taxes the country will receive, and whether local communities were included in the decision making. And if a little-known company is looking to drill for oil in your region, perhaps you can dig into business records to find out what international corporation backs them and where the profits are headed.

Additional Resources

Reporting on Climate Injustice in One of the Hottest Towns in America

How a Comic Series Reveals Heavy Metal Poisoning in Peru

GIJN Climate Change Reporting Guide: Investigating Methane Leaks and Emissions

![]() SEJournal Online is the weekly digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

SEJournal Online is the weekly digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Mark Olalde is an environment reporter with ProPublica’s Southwest team and an adjunct faculty member at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University. His investigations have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, USA Today, High Country News, and the Center for Public Integrity. He has reported from across the US, the Caribbean, and southern Africa.

Mark Olalde is an environment reporter with ProPublica’s Southwest team and an adjunct faculty member at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University. His investigations have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, USA Today, High Country News, and the Center for Public Integrity. He has reported from across the US, the Caribbean, and southern Africa.