BBC Newsnight editors put together a dedicated NHS unit with a brief of investigating stories about failures of care. Image: Screenshot, BBC iPlayer

How BBC Newsnight Exposed British Healthcare Scandals

Read this article in

Each country has its own healthcare issues — whether lack of access to essential services, increasing poverty, health inequalities, or the effects of the private sector’s involvement in care. As spending on health has reached a new high in recent years — approximately 11% of global GDP — and challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic have affected us all, newsrooms and journalists worldwide will find a wealth of public interest health stories worth investigating.

In June 2022, editors from BBC Newsnight, the British broadcaster’s flagship daily news and current affairs program, put together a small group of investigative journalists, a correspondent, and a senior cameraman, with a brief to investigate failures of care inside England’s taxpayer-funded National Health Service (NHS), as well as the impact on patients, their families, and NHS professionals on the frontline.

As we began to dig into the data, submit information requests, and speak to those behind the scenes in hospitals, doctors’ practices, and ambulance services, an initial month-long project developed into over a year of award-winning investigations, including a Medical Journalists’ Association award for Feature of the Year in the Broadcast category.

Below, we share some lessons learned from three of BBC Newsnight’s standout investigations on the NHS.

Hospital Trust with a Culture ‘Like the Mafia’

In December 2022, we investigated one of England’s biggest — and worst-performing — hospital trusts, based in the city of Birmingham. Whistleblowers told the BBC that the trust was “like the mafia,” where a climate of fear among staff was putting patients at risk. One whistleblower told us that there was a lack of “ownership” of patients, and issues with communication among senior clinicians. In some cases, they alleged, this meant that patients had died without receiving any treatment.

Another whistleblower claimed that those who raised concerns were subjected to “victimization and retribution” through referrals to the General Medical Council (GMC), the UK’s independent regulator of doctors. He was referred to the GMC in 2017, several months after raising concerns about a lack of nurses to support operations. One patient’s daughter also claimed that staff knew there were problems with her father’s care before he died from sepsis, but due to the culture at the trust were too scared to speak up.

Newsnight’s investigations led to three major reviews into patient safety, culture, and leadership at the trust, and the UK cabinet official in charge of health policy at the time of our reporting said that the reports from whistleblowers “must be acted on.” The first review, which focused on patient safety, “confirmed some… of the concerns made on the Newsnight program,” and a subsequent review on culture noted that more than 50% of staff members had felt bullied or harassed, but avoided speaking out due to fear of becoming a target.

Tips:

- Start with the data: When starting our investigation, we looked at official data on the worst-performing hospital trusts and started digging into why there were so many documented issues in Birmingham. In England, data is published by NHS Digital, but also by charities or think tanks, such as the Health Foundation, Nuffield Trust, and The King’s Fund.

- Collaborate with local journalists: We worked on this investigation alongside a health correspondent from BBC Midlands Today, who connected us with contacts that he had already established and provided useful background regarding the ongoing issues at the trust.

- Build networks of sources: Many sources talked to us off the record, which was useful in establishing certain areas that we should be focusing on. We also worked with NHS campaigners who had information from FOI requests that they shared with us, which was helpful when working to tight deadlines.

- Follow up on leads after the original story: This investigation continued for many months after our first report, as we followed up on leads that came in from each story. Establishing a method to follow up on additional information and continue the investigation is essential.

Ambulance Handover Delays

One of the first issues that NHS insiders told us about was ambulance handover delays. When a patient arrives at hospital by ambulance in England, the NHS standard is that they should be handed over to the emergency department within 15 minutes. Staff shared data with us showing that ambulances were now waiting longer than ever to hand patients over due to overcrowding and a lack of available beds, and as a result, paramedics could not attend to other seriously ill patients.

A paramedic told Newsnight that the service was on the “fringe of collapse.” Image: Screenshot, BBC News YouTube

Using this unpublished data, we agreed that an on-the-ground approach would allow us to observe the scale and duration of delays ourselves. Local student journalists armed with a form for monitoring ambulances and their phone cameras spent a day at six hospitals with the longest delays, noting down the vehicle registration numbers, when they arrived, and when they left the emergency department.

The results produced a frightening insight into the scale of delays across the country. We found that some ambulances were waiting in line for 11 hours to discharge their patients, and at some hospitals, up to 25 ambulances were waiting at one time. When we repeated the exercise a few months later, the longest an ambulance had to wait to hand over a patient was 21 hours. “We’re right on the fringe of collapse right now,” an anonymous paramedic told Newsnight. “People are phoning and being told that they’re not going to get an ambulance for six or nine hours.”

Tips:

- Invest time in shoe-leather reporting: If the data is lacking, get on the ground, particularly with eager student journalists. We found that the video recordings were extremely visually effective, despite them being taken from phones.

- Cultivate insiders: Speak to trustworthy insiders off-the-record for background information. They may also provide data collected internally that isn’t publicly available.

- FOI requests: Gain as much extra data as possible from FOI requests. Thanks to one request, we found that the number of people in one region who had died after an ambulance delay had risen significantly since the previous year, from one to 37.

- Brief journalists properly: When filming, ensure that there are no restrictions in certain locations (i.e. filming from a public footpath is preferable over hospital grounds). Keep in mind the risks surrounding patient confidentiality, and be sure that journalists are fully briefed on what to do if asked to leave the location.

Access to Doctors in Disadvantaged Areas

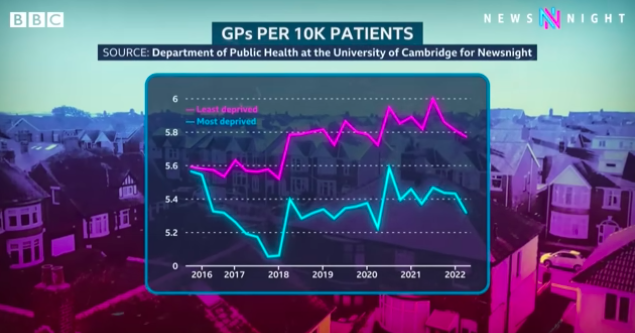

By conducting our own data analysis, and working with researchers from the University of Cambridge who created a separate dataset, we found that there were stark inequalities in the distribution of general practitioners (GPs) — or doctors — depending on the socioeconomic status of a given area. Patients living in areas with a lower socioeconomic level had fewer doctors per head of population, and a worse experience of doctor appointments than their more advantaged counterparts.

For our analysis, we mapped national, public data on disadvantaged areas against the results of the GP Patient Survey, an independent patient experience survey sent out to over two million people in England. We chose to look at the responses to three main questions: overall experience, how easy it was to contact their GP practice via phone, and whether it was difficult to make an appointment — and found that satisfaction was lower amongst those living in poorer or disadvantaged areas.

Cambridge researchers created an interactive dashboard showing regional inequalities in access to doctors. They analyzed levels of staffing per 10,000 patients for each doctor’s practice to show that in the poorest areas, the number of doctors had shrunk between 2015 and 2022, while that number had increased in more affluent areas. We spoke to people in Blackpool — one of the poorest areas in the country — who said that a lack of doctors has caused children to seek medical help from youth workers who aren’t medically qualified.

Data analysis for Newsnight by the University of Cambridge showed that England’s most disadvantaged had fewer GPs (doctors). Image: Screenshot, BBC News YouTube

Tips:

- Collaborate with academics: Where the data is complex or already being worked on by academics, collaborating can be helpful. It may be possible to agree that any new data is shared exclusively with your team.

- Use a small area as a case study: We honed in on Blackpool, one of the UK’s poorest and most disadvantaged regions. We knew that those who lived there were dealing with deeper, more complex health challenges (such as high rates of smoking in pregnancy), so we used it as a case study — speaking to doctors, patients, health campaigning groups, and those who worked in local authorities, who confirmed that the data represented the difficulties they faced.

- Build on a hypothesis: The so-called ‘inverse care law’ — where “socially disadvantaged people receive less, and lower-quality, healthcare despite having greater need” — has been widely accepted for decades, but we set out to test a theory that in the last few years, the gap between access for rich and poor has widened significantly.

- Use door knocking as well as social media: We spoke to patients who had left reviews for their doctor’s practice on Google or had discussed their healthcare via social media, but we also spent a day door-knocking in Blackpool to hear from local residents, which helped to improve the diversity of voices where there is a documented knowledge and access gap in digital literacy.

Emily O’Sullivan is an editorial assistant at GIJN. She has worked as an investigative researcher for BBC Panorama, and is currently an assistant producer for BBC Newsnight’s NHS Unit. She has an MA in Investigative Journalism from City, University of London.

Emily O’Sullivan is an editorial assistant at GIJN. She has worked as an investigative researcher for BBC Panorama, and is currently an assistant producer for BBC Newsnight’s NHS Unit. She has an MA in Investigative Journalism from City, University of London.

Charlotte Rowles is a producer with BBC Newsnight. She has worked on investigations for BBC Panorama and Channel 4 Dispatches. She won a Medical Journalists’ Association award for her coverage of complex health investigations.

Charlotte Rowles is a producer with BBC Newsnight. She has worked on investigations for BBC Panorama and Channel 4 Dispatches. She won a Medical Journalists’ Association award for her coverage of complex health investigations.

Sean Clare is Newsnight’s senior investigations producer. He is an award-winning film-maker and journalist whose work on the NHS was recognized by the Royal Television Society. He has held various senior production and reporting roles at the BBC.

Sean Clare is Newsnight’s senior investigations producer. He is an award-winning film-maker and journalist whose work on the NHS was recognized by the Royal Television Society. He has held various senior production and reporting roles at the BBC.