How They Did It: Inside a Mega-Collaboration on the US-Mexico Wall

When it comes to collaboration, newsrooms often have mental barriers to overcome. Concerns about who will be in charge of the project, as well as a lack of focus and general disinterest or distrust of working with others, are some of the most common issues that come into play.

When it comes to collaboration, newsrooms often have mental barriers to overcome. Concerns about who will be in charge of the project, as well as a lack of focus and general disinterest or distrust of working with others, are some of the most common issues that come into play.

But one of the largest journalism collaborations of 2017 — based on a proposed physical barrier — proved that working together can produce stronger results.

When Nicole Carroll, the editor and vice president of news at The Arizona Republic, joined her reporting staff at a Donald Trump rally in Arizona in the fall of 2016, one particular thing stood out while her group was standing in the press corral: the repeated chants of “Build the Wall!”

They noticed the chants didn’t just sound like a slogan — they seemed to be a true, motivating factor for so many people at the rally.

That prompted Carroll to envision The Wall, a project that involved The Arizona Republic, USA Today and journalists in the USA Today Network from around the country. Together they spent six months reporting on core questions about Trump’s push for a wall along the 2,000 miles of the US border with Mexico.

“We wondered how much people really understood (or didn’t) about the border itself, the current fencing on the border, the reality of the terrain and distance involved,” said Josh Susong, news director at The Arizona Republic, who served as a lead content editor for The Wall. “We began brainstorming some specific stories that would answer these questions from specific locations, a list that grew as other southwest newsrooms joined the team.

“We were confident most of the country had never seen the border and didn’t know about life in cities near it. Our questions evolved into a process of seeking out unknown stories from the border and unintended consequences of border security and a border wall.”

A Multi-Platform Project

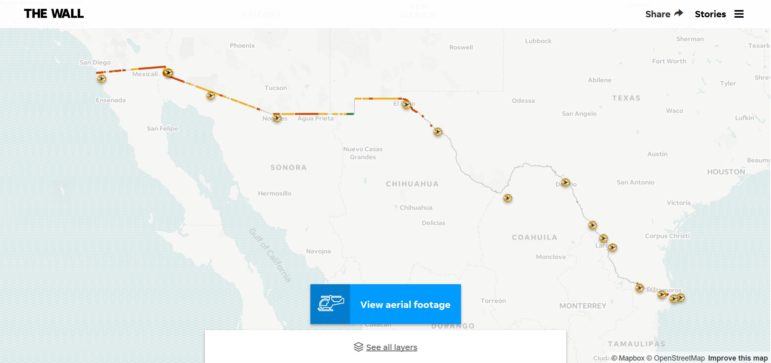

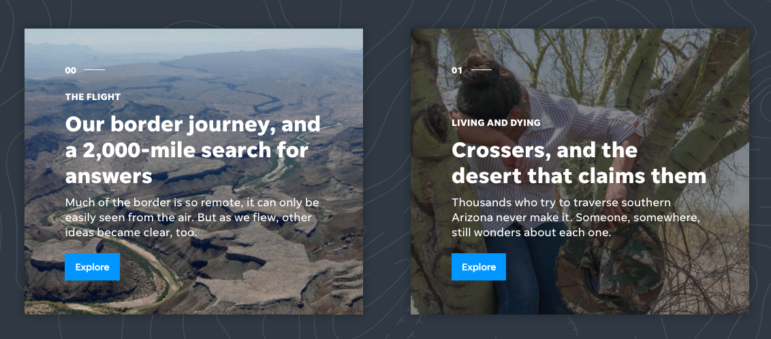

The Wall featured a variety of different storytelling methods: print publication, digital publication, documentary videos, virtual reality, an interactive map, podcasts, chatbots, live storytelling nights and a newsletter. The journalists boarded a helicopter to fly, film and observe every foot of the border with Mexico, from Texas to California. They also drove the entire border.

Reporters and photographers interviewed everyone from human smugglers to families and farmers along the border. They spent time with Border Patrol agents, vigilantes and ranchers. Story topics included deaths of those attempting to cross the border, deaths of agents protecting the border, drug trafficking and concerns of Native Americans along the border. The newsrooms also dug into the effects of the wall on prices of goods like produce, and found out from a smuggler that a new border wall will allow him to charge more for his services.

The audience can watch aerial footage collected of every foot of land along the border, explore the most current and comprehensive map of current border fencing and visit Big Bend National Park and other spots along the border with a Vive VR headset.

Susong said the idea for storytelling on multiple platforms was a goal from the very beginning. Annette Meade, innovation director in the Gannett Innovation Lab, was a lead project manager who helped track all the technical elements of the project and ensure the technology efforts matched the content efforts.

In all, the project included a fully interactive map with about 20 hours of aerial footage of the border, a seven-chapter story about the journey, 14 additional stories about the consequences of the wall, 14 mini-documentaries and an explanation of the history of the border itself.

Special immersive views of key points along the border were built for virtual reality using the HTC Vive system. The project staff talked about the stories behind the stories in a 10-part podcast series that featured an interactive chatbot that could automatically send listeners more details about a story. And the audience joined the conversation for live storytelling events in three states.

Building a Coalition

The first planning note about the project went out on December 30, 2016. Editors at USA Today Network’s southwestern properties, led by Carroll, helped flesh out the project idea and generated a list of likely storylines to pursue.

Two months were spent pitching and refining ideas with all stakeholders, including people in editorial, digital, video, marketing, advertising and corporate communications. Detailed documentation, including an 80-page deck, was put together for Carroll and others to help pitch and explain the project to the people who worked in all those different parts of the organization, and whose expertise and support would be needed.

In total on its credits page, The Wall lists nearly 130 individuals who contributed to the project, including reporters, photographers, graphic artists, videographers and designers.

Reporting came from more than 30 journalists in the field, primarily from USA Today Network’s newsrooms in Palm Springs; Phoenix; Las Cruces, New Mexico; El Paso and Corpus Christi, Texas; with more support from newsrooms in Ventura, California; Detroit; and DC.

The Wall also involved a documentary editor and executive producer from Detroit, who led the video process. The network’s emerging tech lab spearheaded the VR process. The digital team included developers and staff in Virginia, New York and elsewhere. The project did have help from outside the network — Jam3, a digital design and development agency, assisted with early work envisioning the framework and digital navigation. Aerial Filmworks managed the helicopter shoot. Finally, Arizona State University students were hired to help review the aerial footage. An in-house development team then linked the map to the video.

Taking Advantage of the Network

The Wall, according to Susong, was perhaps the company’s biggest example yet of the strength of the company’s national network of journalists. He said The Arizona Republic had collaborated before on many things, particularly breaking news, but never anything on this scale.

One of the first tasks was developing the project idea with editors in all of the southwestern locations. Local editors brought in the staff they knew were best qualified to use local connections to help determine local storylines.

While reporting in the field, the majority of the work was done in teams — partly because they were capturing documentary video. Each visuals team had at least two people, plus at least one local reporter. Most of the field shooting was done by four visuals staffers from The Arizona Republic.

“We weren’t parachuting in to do this story,” Carroll said. “We live and work here. Many times, our journalists got access and interviews because they were local. For example, we were having a hard time getting access to the border patrol in southern New Mexico. Our reporter from Las Cruces made the request and the team got in. She grew up in New Mexico’s Bootheel area, and had been covering the area for years.”

Communication for Collaboration

As you might imagine with a project of this size, communication was key. Some of the technology used included:

- Developers did much of their work using Slack.

- Some teams used Basecamp work groups to stay connected.

- The project used a shared spreadsheet to determine budgets for content. It listed every possible piece of content in all of their various forms, including every fence photo with geo-coordinates. Susong said the spreadsheet had 20 tabs and thousands of lines of entries by the end of the project.

- Project leaders from across the country held regular conference calls during the year of planning and reporting. At first the calls were every two weeks but that changed to weekly and almost daily as launch date approached. Susong said one of the most important parts of these calls was to know for sure who owned a decision on the content — issues like whether a story lived or was killed, whether there was time to shoot more interviews and progress of digital features.

- Video editors and producers shared physical hard drives to complete work. The dozens of hours of aerial footage alone had to be downloaded and processed to these hard drives during overnight hours each night while the helicopter wasn’t flying. The drives were then shipped or driven back to the newsroom. Susong said the logistics were intense, and Emmanuel Lozano, a video producer, ran this process — which included flying and driving the entire trip.

Editorial Process and Launch

Story text was edited inside the network’s proprietary CMS by the local editor for that reporter on-site, but Susong worked with those editors to set the theme and structure of each story. He also served as a second editor to make sure the pieces of content shared a common editorial style and voice.

Story text was edited inside the network’s proprietary CMS by the local editor for that reporter on-site, but Susong worked with those editors to set the theme and structure of each story. He also served as a second editor to make sure the pieces of content shared a common editorial style and voice.

A similar model was used for other platforms. With video, for instance, Kathy Kieliszewski, photo and video director at the Detroit Free Press who served as the executive producer for The Wall videos, helped set the theme and standards.

Stories ultimately went through one of the network’s top copy editors, Melissa Galbraith, a digital producer at The Arizona Republic. Galbraith also wrote most of the cutlines (captions) for the hundreds of photos and, along with Susong, wrote most of the display copy for the stories.

Carroll and Kevin Poortinga, the vice president of innovation at Gannett, along with Susong and Meade, met twice at USA Today’s headquarters with leaders from across the network who were helping to support and promote The Wall, including the graphic artists who built the map, the virtual reality team, social media managers, print and digital planners and many more. In addition to the many other points of coordination, the in-person check-ins were critical.

“These series of connecting points helped keep many people in the loop on what the project was about, what was coming and how they could support it and promote it when it was finished,” Susong said.

In print, all of the USA Today Network’s 109 newspapers nationwide ran a version of the project launch story on their front page.

After that, all the network’s newsrooms were free to use as much of the content as they could. The Arizona Republic ran every word produced over the course of two weeks. The Corpus Christi, Palm Springs and El Paso newspapers ran most or all of the stories in their pages as well. USA Today ran most of the pieces in its print edition, including a double-truck print version of the map.

Online, every newsroom in the country featured the same digital pieces, which were all housed at thewall.usatoday.com. Some were featured on the home pages of local sites. In addition, the network’s storytelling studio coordinated three live storytelling nights, which took place in Phoenix, Arizona, Indio, California, and El Paso, Texas, where men and women from across the southwest shared their first-person experiences of living on the border.

Cost and Metrics

Cost is always a consideration when working on a project of this size. The Arizona Republic declined to disclose how much money was spent on the year of reporting, but Susong said the network did receive more than $30,000 in grants to complete some components.

With so many moving parts, tracking success of the project was another challenge. Susong said the short-term, quantitative goal was to hit 5 million page views, which they’ve already surpassed and are now closer to 6 million page views.

In a collaboration this detailed, it could have been easy to lose direction. Carroll said they often had conversations about the scope of the project, but they always insisted on staying focused on the wall — not immigration, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or any other related issue in the news. The coalition also celebrated short-term wins like getting a key interview or solving a technical issue.

In the end, a project of this scale was only possible because of combining resources and working together with others.

“There is power in collaboration,” Carroll said. “We were able to do far more together than we could have ever attempted as individual organizations.”

Lessons Learned

We asked leaders of The Wall to share some of the key lessons they learned from the collaboration that will help them in such projects in the future. Here’s what they said:

Nicole Carroll, vice president/news and executive editor, The Arizona Republic and AZCentral.com:

Have a clear goal, and make sure everything you do supports that goal. In this case, we wanted to educate America about the impact, cost and feasibility of a border wall. We wanted to be as transparent as possible, so people could see the information for themselves and hear directly from those impacted. As we made decisions, this gave us guideposts: “Should we/could we map every piece of the current fence?” (Yes, this educates our audience.) “How can we be more transparent?” (Let’s do behind-the-scenes podcasts.)

Be mindful about the team. Projects like this are powerful career-development and skill-building opportunities. We made sure to have a mix of veteran and newer journalists, from many different areas and backgrounds, to have diverse voices and approaches, to give opportunities to a wide group of people.

Annette Meade, innovation director, Gannett Innovation Lab:

Understand the skill sets and experience of the people who are working on the project and make sure that tasks/timelines match up with those skills. If you have a person on the team who is less experienced or new to this kind of project work, build time in to allow them to learn along the way. Check in with them as often as needed and embrace the fresh viewpoints or ideas that they can bring to the process.

Tap resources from around your organization. Your core team is likely to be relatively small, and they won’t know everything about everything. Pull in the best people you know to address specific areas, like SEO.

Allow enough time for QA (quality assurance)/testing. Anticipate the worst-case scenario, where development gets backed up a few days (or more), and plan accordingly when you build in QA time. Then just to be safe, add in a little more time. We seldom see projects that allow too much time for QA/testing; it’s usually just the opposite.

Kevin Poortinga, vice president, innovation, USA Today Network/Gannett:

New long-distance relationships: Rough but so worth it. Not only did we wrestle with multiple time zones, we also wrestled with new-to-each-other work styles (and this was without the benefit of in-person happy hours to talk it out). We prevailed, and we’re so much better off now for future projects, as it immensely eases that outreach going forward. In this company, we should all fight to rotate who we work with at least a few times each year to extend our networks.

On such a large project involving so many players and stakeholders, it’s going to be a roller coaster of an experience. As much as you want the process to be a smooth, straight A-to-Z ride from both a process and people perspective, it’s going to look a lot more like this:

It’s best to be upfront about this, and set expectations about how you’ll have the necessary discussions along the way.

Josh Susong, senior news director, The Arizona Republic/AZCentral.com:

Appoint one person to know the location of all the digital/visual media. We relearn the value of this on every big project we do. In this case it was Emmanuel Lozano. Whoever it is, somebody needs to own knowing where every visual thing lives, to feed the many designers, developers, social planners, etc., who are all looking for the one last extra image of <fill in the blank>.

Kathy Kieliszewski, photo and video director, Detroit Free Press:

When producing a documentary, a lot of time is spent on pre-production — building sources, navigating new territory and chopping through red tape. With this film, we were able to leap past that in a lot of ways by utilizing the institutional knowledge of the network’s news organization along the border. That’s given us an incredible leg-up in telling the stories of how the proposed border wall could impact those communities.

The Wall was awarded a $7,000 grant by the Center for Cooperative Media as part of an open call to fund collaborative reporting projects, which was made possible with support from the Rita Allen Foundation and the Democracy Fund. This story first appeared on the Center for Cooperative Media’s Medium site and is reproduced here with permission.

Dale Blasingame is a senior lecturer in the School of Journalism at Texas State Univ. in San Marcos, Texas. Among the courses he teaches: fundamentals of digital media, web design and publishing, digital media entrepreneurship and social media analytics. Blasingame spent nine years as a TV news producer and won two regional Emmy Awards.

Dale Blasingame is a senior lecturer in the School of Journalism at Texas State Univ. in San Marcos, Texas. Among the courses he teaches: fundamentals of digital media, web design and publishing, digital media entrepreneurship and social media analytics. Blasingame spent nine years as a TV news producer and won two regional Emmy Awards.