How Local Reporters in India Exposed the Pandemic’s True Death Toll

Read this article in

A worker helps cremate bodies of COVID-19 victims on the banks of the Ganges river in Uttar Pradesh. Image: Shutterstock

Through April and May, government figures of COVID-19 deaths and infections were suspiciously low from the populous Indian state of Gujarat, north of Mumbai. The reported numbers were sometimes as low as in the single digits in major cities, even as local hospitals and crematoria were overflowing. Like most reporters, Yogen Joshi, a senior journalist in the city of Baroda, with the Gujarati newspaper Gujarat Samachar, knew the official data was unreliable.

So how could he investigate the true toll? An hour away from his office, a holy spot on the banks of the Narmada river has long been used by Hindus to immerse the ashes of their loved ones. “I suddenly had an idea, why not see what was happening there?” he recalls. On May 18, Joshi staked out the tiny village of Chanod, where the movements in a small parking lot revealed Gujarat’s tragedy being played out. Speaking to priests, boatmen, and parking lot attendants, he learned the scale of daily activity had sharply spiked.

On May 22, his newspaper carried a story revealing that more than 32,000 “asthi visarjans” or immersion of ashes — a traditional Hindu funerary rite — had taken place in the river between March 15 and May 18. That was an average of at least 492 per day, compared to the pre-pandemic high of 150 per day. The official state-wide death tally between March 1 and May 10: just 4,218 — or 59 fatalities a day. “I wanted to show what the impact of the second wave was,” he says. “The government figures were different.”

Reporters in local and regional dailies across India have been finding ways to report on the death and devastation of the second wave of the coronavirus, despite government intransigence. The press in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state of Gujarat has been particularly relentless in counting the dead, reporting from hospitals, morgues, and crematoria, finding creative ways to tell the story of how the state government has downplayed the severity of COVID-19. And while these stories were predominantly written for a local audience, they have sent ripples around the country as they are read by audiences far beyond the state.

A Stifling of the Press

Images of India’s battle against the second wave were broadcast around the world: patients hooked up to oxygen waiting outside hospitals; bodies lined up in queues waiting to be given last rites; desperate family members. More than 395,000 people in India have died from COVID-19, and the country is second only to the United States in overall cases, with daily infection records being set during the worst of the second wave in early May.

Gujarat Samachar, the newspaper that revealed the scale of the crisis through the ashes being immersed in the river. Image: Screenshot

This death toll includes hundreds of journalists, as many 500 according to one count by NWMI India. Reporters are working despite the serious health risks and against a backdrop of shrinking media freedoms, attacks, and threats under Modi’s Hindu nationalist government, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

India ranks 142nd out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, which notes that since the reelection of Modi in 2019, “pressure has increased on the media to toe the Hindu nationalist government’s line.”

According to one report, by the independent think tank Rights & Risks Analysis Group, at least 55 journalists faced punitive action during India’s first, chaotic two-month national lockdown last year. By another estimate, 67 police cases were lodged against journalists in 2020, more than double any other year in the past decade.

“Under the present regime, any media exposure of the state is termed anti-national,” says Kalpana Sharma, a journalist and author who writes the “Broken News” column for Newslaundry, an Indian media analysis site.

But despite the government’s hostility to critical comments or coverage, journalists around the country are pushing back. When the state failed to provide accurate numbers of those succumbing to COVID-19, reporters, many from smaller, regional outlets, set out to count the deaths themselves.

“Big media houses and television channels, with a few exceptions despite all their resources, did not do the kind of reporting we saw from some regional media and smaller digital outlets,” Sharma explains. “Public health reporting has to be shoe-leather reporting. There are no shortcuts to going on the ground.”

Counting Bodies, Telling Truths

Journalists have shown remarkable perseverance and bravery through the pandemic, finding ways to tell stories in the absence of accurate official data: from counting dead bodies to tracking last rites to highlighting mismatched statistics from different government authorities.

In Ahmedabad, the largest city in Gujarat, a team of reporters from local daily Sandesh spent a night in April driving to 21 crematoria to see how many bodies were being cremated under COVID-19 protocols. Where the state government had claimed 25 deaths on a particular day, the reporters found more than 200 in Hindu funeral homes alone. Another team of reporters from the same paper spent 17 hours outside a government COVID-19 hospital wing counting the number of corpses. On April 13, the paper reported that, in just one hospital, its reporters counted 64 deaths. The government figure for Ahmedabad that day: 20.

When Om Gaur, national editor for Dainik Bhaskar, one of the country’s biggest Hindi dailies, heard that bodies set adrift in the Ganges river were washing up on river banks in the neighboring state, he set to work. Gaur assembled a team of 30 reporters across 27 districts in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, with over 200 million people. On May 14, the paper’s headline read: “Ganga Ashamed.” Over a 1,140 kilometer (700 mile) stretch, his reporters counted more than 2,000 bodies. “From the ground, a terrifying picture emerged,” Gaur says. “There were bodies every step of the way.”

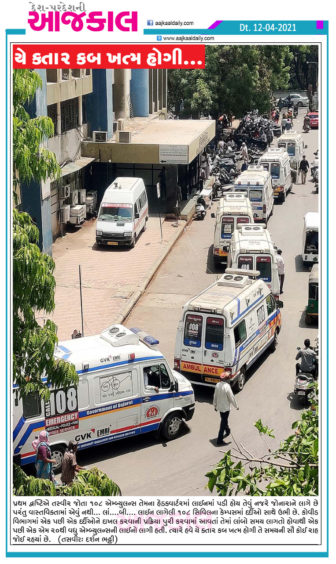

Ambulances queue outside a hospital in the middle of the Indian second wave. Image: Courtesy Jayesh Thakrar

“In my 35 years as a journalist I had not seen something like this,” Gaur adds. The paper wrote about the findings and provided readers with videos and photos from the scene.

Standing in front of pyres on a footpath outside a crematorium in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, Lokesh Rai eviscerated the district administration’s claims of single-digit COVID-19 deaths in an April 18 broadcast. “These burning pyres are proof of the gaping difference between official figures and reality,” he said in a clip for Bharat Samachar, a Hindi television channel. “Some of these will never be counted.” Rai further reported that in the preceding five days the government had reported just two COVID-19 deaths, whereas 35 to 40 bodies were being brought every day to the site where he was reporting, at least half of them COVID-19 fatalities.

Rai and a colleague went to the site after locals started calling them and sending them videos. “If the government was transparent with its data we would not have to keep risking ourselves and coming out like this,” he said.

In April, as cases climbed, journalists were not considered frontline workers in most states, and were ineligible for vaccination unless they were over 45. That left reporters trying to decide whether to risk their health, or their jobs. “I didn’t like it at first that our bosses were sending us to places of death and infection,” said one reporter who was particularly concerned about bringing the virus home. “But it was my work and boss’ orders, so I had to go.”

Using Data to Expose the Real Impact

Government data has itself been inconsistent. Sandesh, for instance, reported how district-level data differed from state-level data, both of which fell short of the numbers the paper tallied. Extracting death records was another way of exposing the truth. Both Divya Bhaskar, a Gujarati daily, and Amar Ujala, a Hindi paper published in six states, investigated the difference between death certificates issued over the same period this year and last year in a particular area.

“The authorities were suppressing data so I got it through a source how death certificates had doubled this time in April,” explains Rajeev Sharma, an Amar Ujala reporter whose May 17 story compared the death certificates issued by local authorities in Ghaziabad this April (973) to last April (446). “And even that will probably increase because many people would not have been able to get deaths registered during the lockdown.”

“If the true picture were known, people might have understood the seriousness of the situation,” Sharma adds. “But suppressing the data has aggravated the problem.”

Vishal Mistry and his colleagues working for the Lok Satta Jan Satta newspaper in Gujarat’s Narmada district were able to gauge discrepancies in the coronavirus statistics another way. For a period, the government was tracking COVID-positive households by placing boards outside their homes. If the health authorities claimed there were 25 cases in a particular area, the team would fan out to see if that checked out, based on the number of notices outside homes.

Even so, it was often impossible to know what was happening in far-flung rural areas, where the second wave was particularly devastating. Jayesh Thakrar, a resident editor with Sandesh in Saurashtra, a region in Gujarat, told team members to call five local village heads every day to understand the situation there. Thakrar also extended the deadline for accepting death notices, and for 15 days dedicated two staffers to handling obituaries, as that section’s pages ballooned from two or three a day to seven or eight.

Thakrar himself went out into the field to motivate and lead his team, filing reports from hospitals. “If my son asks me 10 years later ‘What did you do?’ I will have an answer that I did something,” he says.

A Watchdog Press Reawakening?

As a result of critical reporting on the government’s response, officials warned hospital staffers and crematorium workers not to speak to journalists. Government workers also refused to take calls sometimes, or privately berated reporters, urging them to print “positive” stories as well, journalists consulted for this story said. In some cases, officials were even stationed at crematoria to monitor media visitors, while death registers were hidden out of public view.

Kalpana Sharma says some media outlets that had been sympathetic to the government in the past took a more watchdog turn, even in BJP-controlled states. “This crisis was greater than politics and no self-respecting editor could ignore that.”

But the pressure on reporters also comes from within their communities. Saurav Kumar, a freelancer in rural Bihar, a state in the east of the country, says reporters risked being stigmatized by their villages if they reported on COVID-19, but that the Hindi-language media had risen to the occasion. “I thought some outlets had been co-opted by the authorities, but they have been trying to report the truth,” he notes. “No one has been left untouched by this disease.”

Kumar, who contributes to NewsClick, an English-language site, says harassment or intimidation was familiar to him and his colleagues. “When you report on anything controversial, your work could be hindered or cases slapped against you,” he says. “In states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, this is a 365-days-a-year phenomenon.”

Additional Resources

Tips for Journalists Covering COVID-19

GIJN Webinar: Staying Safe: How to Report A Pandemic

How to Tackle the Global Undercount in COVID-19 Deaths

Bhavya Dore is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai, India. Her work has been published by The Caravan, Quartz, the BBC, and Foreign Policy, among others. She is also a Kim Wall Grantee with the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Bhavya Dore is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai, India. Her work has been published by The Caravan, Quartz, the BBC, and Foreign Policy, among others. She is also a Kim Wall Grantee with the International Women’s Media Foundation.