How Collaboration Enables Transcendent, World-Changing Journalism

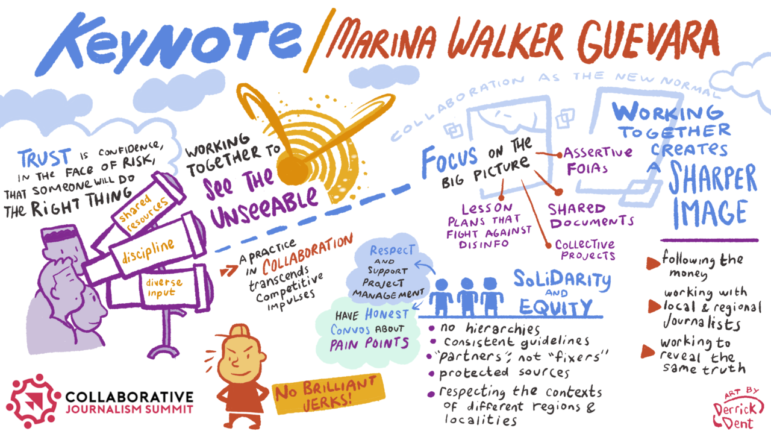

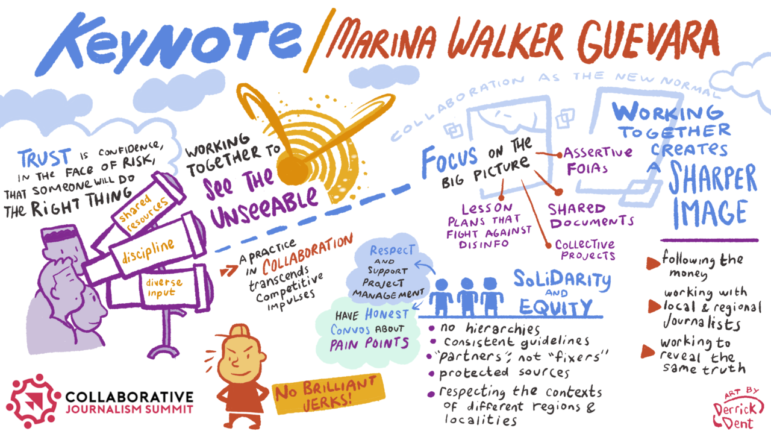

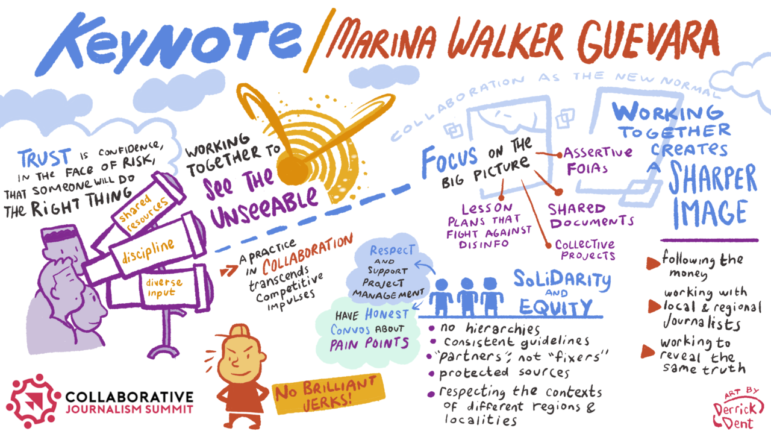

Graphic illustration: Designed in real-time by Derrick Dent during the Collaborative Journalism Summit

Editor’s note: The following keynote address was given by Marina Walker Guevara, the executive editor of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and a board member of GIJN, at the 2022 Collaborative Journalism Summit. It is republished here with permission.

Collaboration has anchored my experience and my career in journalism and allowed me to do things that I never dreamt were possible.

Speaking of impossible ventures, I would like to start with an anecdote from another discipline that has resonated deeply with me as I reflect about our achievements and challenges in journalism.

On April 10, 2019, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, declared at a press conference: “We have seen what we thought was unseeable.” They were referring to the first-ever photograph of a black hole, something that until that point had been considered impossible because to accomplish that scientists would have needed a telescope the size of the Earth.

So instead, 200 scientists joined forces and created a network of synchronized radio telescopes that were set to focus on the same object at the same time and “act as a giant virtual telescope.” The more telescopes involved, the sharper the image.

As The New York Times put it, the scientists had to adjust the telescopes to work together; they had to get the timing right; they had to hope that the weather would cooperate in multiple places. “Oh, and they had to hope nothing broke. It sounded crazy, but it worked.”

Pioneering collaborative journalism: Marina Walker Guevara of the Pulitzer Center. Image: Marina Walker Guevara.

Now let’s think about journalism and how that kind of cooperation and ingenuity grounded in trust (and a bit of crazy) has allowed us to overcome our limitations, break new ground, and tackle the stories we thought would be impossible to do.

Go no farther than the global pandemic of the past two years. Whether by force or by choice, stuck-at-home journalists have found bold and creative ways to cooperate across newsrooms and countries, discovering in the process a new sense of journalistic solidarity. We used mapping and other digital tools to overcome mobility restrictions, and cooperated with other disciplines — scientists, artists, educators — to get the context and the nuance that makes a story not only compelling but truly relevant to the communities most affected.

As we gather here today, dozens of our colleagues are cooperating across newsrooms and borders — including Ukrainian and Russian journalists working hand in hand — to track Russian oligarch assets, unravel global networks of propaganda and disinformation, and document war crimes.

When humankind is at its lowest, journalists who ground their practice in collaboration are uniquely positioned to tell the crucial stories of our time. They know these stories transcend us, they transcend our competitive instincts, our newsrooms’ politics, and our own egos. So they use technology in smart ways and band together for the sake of truth, to bear witness together, and to get a sharper image of the crises that will shape not only our lives but the lives of generations to come.

Maybe this is a good moment to pause and appreciate what a radical proposition collaboration is in the context of journalism. Just think about all the things we had to unlearn in order to put radical sharing at the center of our reporting. For centuries journalism’s whole ethos revolved around hoarding information, scooping others, getting ahead alone.

The thing is… the world got complicated, interconnected, and increasingly more dangerous, and so did the stories that the lone wolf reporter was trying to tackle in glorified isolation. How do you follow the money across dozens of tax haven jurisdictions where secrecy and opaqueness are protected by law? How do you track commodities that are extracted from the world’s protected rainforests and make their way to luxury fashion and cars in the US? How do you investigate algorithms that are developed in Silicon Valley or Shanghai when the data they are trained on is labeled in the Philippines and used to develop models that are then deployed in several other countries?

We journalists needed our own network to investigate these complex networks and systems. I was fortunate to be part of one of the first attempts at organized journalistic collaboration. Most people learned about the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists when we published the Panama Papers in 2016, and they were surprised to learn that the network had been around since 1998.

Building this network took several years of trial and error, unlearning our old methods, tinkering with technology, and, crucially, learning to trust one another.

Here’s a definition of trust that resonates with me: “Trust is confidence, in the face of risk, that the other person will do the right thing.”

We need to be certain that in the face of risk or pressure our collaborators will do the right thing — observe the embargo, protect sources, give appropriate credit, follow security protocols, and of course do their share of the work. Ultimately, trust is the foundational stone that determines whether a collaboration thrives or crumbles. There’s no digital tool or coordination strategy that can overcome a lack of trust.

Developing deep trust anchored in shared values involves picking your partners right in the first place. My advice is based on my own mistakes and successes: look at the whole person, not only the journalistic skills. Self-awareness, humility, ability to put oneself in somebody else’s shoes, and optimism are all invaluable traits that can help you overcome the most challenging moments in a collaboration. Make sure you have enough of those qualities in your cross-newsroom teams. In other words, as my friend Dawn Garcia says: “No brilliant jerks.”

Also, we don’t collaborate just out of the goodness of our heart, we do it for the sake of the story and the audience. We put the story at the center of all our efforts. Sharing the Panama Papers with 376 other journalists was a decision both practical and philosophical. Technology was only going to help us so much, we needed local knowledge, nuance, and context to interpret the data that only our colleagues in places as disparate as Mexico, Hong Kong, and Burkina Faso could bring to the team.

Collaboration can be a powerful equalizer in the media ecosystem when it centers the role of local journalists so often overlooked by national and global media. When people ask me what was key to get massive collaborations across the finish line, I say the people, the diversity of perspectives, skills, languages, and geographies in the team, and the sense that we were all united by something bigger than ourselves.

We established from the beginning that there were no hierarchies among partners. Everyone had access to the same data and resources and everyone was expected to help one another and follow the same community guidelines whether you worked at the BBC, NPR, or the gutsy Tunisian outlet Inkyfada. There were no “fixers” in our team but reporting partners. The word fixer, in fact, was not tolerated. I hope we quickly agree that it should no longer have a place in journalism.

We shared radically, knowing all too well that any mistakes or breaches of trust could not only derail the story but also the viability of collaboration in journalism. That’s what we felt was at stake.

Some of the memories I cherish the most involve colleagues doing the right thing in small and big ways for the sake of the team. A US colleague who led the request for comment in a repressive country to protect a local partner from retaliation before publication. A partner who shared with us that his editors were not willing to play by the rules thus allowing us to prevent and contain a bad situation. Or a colleague living in a small country who gave up his job at the public broadcasting system to prevent a leak of the Panama Papers findings during the year-long research phase.

That colleague was Johannes Kristjansson, and his Panama Papers story brought down the Prime Minister of Iceland.

I am sure your collaborations are filled with similar moments of kindness, courage, and ingenuity that allow for the most impactful journalism. We also know that collaborations are hard and, if managed poorly, can become a true nightmare.

We owe so much to our colleagues who take on the difficult, crucial, and often thankless job of managing our collaborations. We need more of you in journalism. You navigate from the tree to the woods and back seamlessly, you keep track and make sense of the complexity that goes into our collective research, you anticipate and manage our conflicts and disagreements, and you keep us all focused on the finish line. If you are a project manager, a facilitator, or a cat herder: Thank you so much for your leadership. Please know that you are essential to our profession.

I regard collaboration as one of the most significant paradigm changes in journalism of the past 50 years. It has become the new normal, but you know what an extraordinary shift of mindset and approach it took to get us to where we are today. Many of you were pioneers of these efforts and faced all kinds of skepticism and doubts. You had to work so hard to convince others (including your own editors) that we needed to turn our practice on its head because we were missing the biggest stories of our time.

You remember the raised eyebrows, the uncomfortable questions, the fear in editors’ faces.

And then you persevered and, slowly but surely, we started to see dozens of little fires everywhere. Local collaborations, regional networks, even once-fierce competitors joining forces to tackle a reporting challenge. A couple of years ago, the California Reporting Project showed us how you approach a complex and systemic story like police misconduct as a collective. You get together with trusted colleagues and you FOIA the hell out of police departments, then you share the documents with your 33 newsroom partners and write the stories that were hidden for too long.

Still, we know there is so much more work to do. Are we collaborating enough here in our own backyard in an election year when the core of our democracy — the right to vote — is systematically challenged and eroded in cities and counties across the country? Are our existing reporting networks and collectives creatively and effectively countering the massive disinformation networks that flourish in our communities amplified by social media and talk shows? And how might we deepen our cooperation with other disciplines — human rights researchers, lawyers, artists — to make our work even more ambitious and relevant?

At the Pulitzer Center, where I now work, we have had the privilege to support the creation of the 1619 Teacher Network. This is a collective of teachers from dozens of school districts across the country who have come together to develop lesson plans based on the New York Times’ 1619 Project. The network also allows them to support one another amid widespread attacks and legislation that seeks to make teaching the history of slavery in America illegal.

The challenges we face are perhaps bigger than in any recent memory. But the difference is that this time we, journalists, are better equipped to tackle them. A sense of solidarity and possibility has permeated the media ecosystem in Chicago and California, in Texas, in New York, and in Maine.

We all have gone through a lot in recent years and yet there is great momentum and synergy of people, ideas, and methods.

What is going on in our profession reminds me of those scientists coordinating their telescopes from different corners of the Earth to finally see what until then was unseeable. Remember: the more telescopes involved, the sharper the image of the black hole as long as there was disciplined coordination, trust, and yes, a little bit of luck.

I am counting on this community’s journalistic ingenuity and courage to give us a sharper image of our dwindling democracy, a deeper conversation about the enduring legacy of racism in our country, and bolder ideas on how we might create a more equitable, inclusive, and sustainable media industry.

Here’s to hoping that we continue to reach for the impossible and the unseeable with new tools, deeper determination, and more collaboration.

For more materials from the Collaborative Journalism Summit, which was held in Chicago in May 2022, see the website. The summit was hosted by the Center for Cooperative Media at the School of Communication and Media at Montclair State University.

Additional Resources

The Collaboration That Matched Award-Winning Reporters with University Students

10 Lessons from Our Global Collaboration on Pangolin Trafficking

How They Did It: Methods and Tools Used to Investigate the Paradise Papers

Marina Walker Guevara is executive editor of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and a member of the GIJN Board of Directors. She was previously deputy director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, an independent network of reporters who work together on global stories. Over a 20-year career, she has investigated environmental degradation by mining companies, the global offshore economy, the illicit tobacco trade, and the criminal networks that are depleting the world’s oceans, among other topics. Her stories have appeared in leading international media, including The Washington Post, The Miami Herald, Le Monde and the BBC.

Marina Walker Guevara is executive editor of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and a member of the GIJN Board of Directors. She was previously deputy director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, an independent network of reporters who work together on global stories. Over a 20-year career, she has investigated environmental degradation by mining companies, the global offshore economy, the illicit tobacco trade, and the criminal networks that are depleting the world’s oceans, among other topics. Her stories have appeared in leading international media, including The Washington Post, The Miami Herald, Le Monde and the BBC.