Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano for GIJN

GIJN Marks World Press Freedom Day with Insights from Investigative Journalists Under Threat

Read this article in

For the past 30 years, World Press Freedom Day celebrations have highlighted the right to free expression and emphasized various aspects of press freedom’s importance globally. However, despite the years of meetings and proclamations by its sponsors, UNESCO, and others, conditions are getting worse, not better, for journalists around the globe.

This year’s theme is “Shaping a Future of Rights: Freedom of Expression as a Driver for All Other Human Rights,” a fitting topic in a world where journalists are subject to increasing legal harassment in the UK, safety issues related to covering the war in Ukraine, growing violence in Latin America, and numerous other threats.

Despite this, from Ecuador to Pakistan to Rwanda, independent newsrooms and journalists continue to bravely dig up and report the facts, and hold bad actors to account. As a testament of our support, GIJN marks this World Press Freedom Day (May 3) by highlighting investigative journalists in countries that present some of the biggest challenges and threats to press freedom globally.

Latin America: A ‘Toxic’ Media Environment

In Reporters Without Borders’ most recent World Press Freedom Index, it cautioned that Latin America has become an increasingly “toxic environment” for the press, especially for investigative reporters focused on holding power to account. The Committee to Protect Journalists determined that Latin America was also the deadliest region to practice journalism in 2022, documenting 30 journalists killed in Latin America during the year — nearly half of the global total.

Image: GIJN

In a recent conversation with the GIJN Español team, Nelly Luna, journalist and director of the Peruvian news site OjoPúblico, said she and her colleagues have witnessed democracy under attack by organized crime groups and dictatorships throughout Latin America.

Luna said threats to press freedom are also increasing across the region, and cited examples including an epidemic of murders in Mexico as well as the political and judicial persecution of reporters in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. In addition to this, she has witnessed an increase in hate speech and attacks by politicians.

In her home country of Peru, Luna said that journalism is currently practiced under a regime in which, to carry out their work and cover citizen protests, journalists deem it necessary to be equipped with gas masks, helmets, and bulletproof vests.

In just the last few months, 66 people connected to these protests have died, and hundreds more have been injured. According to Luna, the majority of those wounded or killed had been shot.

Image: GIJN

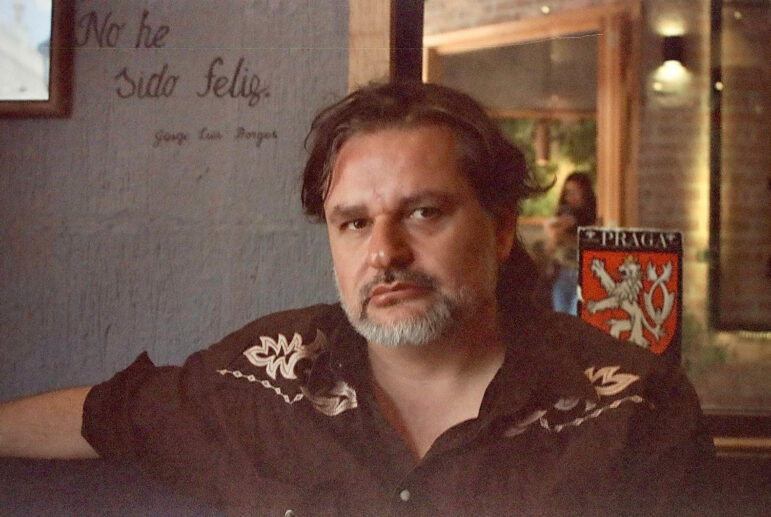

One of the most prominent Mexican investigative journalists, Anabel Hernández, also spoke with the GIJN Español team about the growing threats to press freedom in her region.

Hernandez explained that for press freedom to exist, the media must be able to act independently of group interests and without pressure, censorship, or self-censorship.

“I believe that teamwork between people who share the same codes of ethics and ideals is the best way to face the problems of freedom of the press. United, not divided. Division is the biggest weakness of journalists and media in Mexico,” Hernández said.

After various assassination attempts against Hernández and her family, and the inability of the Mexican state to prosecute those responsible, she has been forced to go into exile to protect her family and to continue her reporting.

Pakistan: Prone to Violence

This year, Pakistan experienced several political crises, including a change in leadership when Prime Minister Imran Khan stepped down in April after he lost a vote of no confidence.

The turmoil in Khan’s party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), has created an environment ripe for journalists to dig into various aspects of its government — and its supporters’ propensity for violence.

Image: GIJN

In May 2021, three unidentified men broke into the apartment of Asad Ali Toor, a prominent Pakistani journalist who had previously criticized the government and the country’s military. These men also tied him up and beat him with a pistol.

Recently, Toor spoke with GIJN Urdu editor Amel Ghani about the current challenges facing press freedom in Pakistan.

According to Toor, the Pakistani military establishment has aggressively invested in fake news campaigns through propagandists who propagate the state narrative, but who also launch attacks to discredit independent and reputable journalists. Simultaneously, a parallel breed of self-proclaimed, pseudo-“investigative journalists” has arisen, who promote government briefings and documents, and as a result, its agenda.

Toor’s advice? Be resilient and try to switch to alternate forums for fact-based reporting.

Russia: Banning Independent Media

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, almost all independent media have been banned, blocked, or declared “foreign agents.” Journalists in surrounding countries have also been subject to deportation and arbitrary arrests.

Image: GIJN

Anti-corruption investigative journalist Bolot Temirov, who holds both Russian and Kyrgyz citizenship, was arrested in January 2021 after a raid on his company — Temirov Live, where the journalist said officers planted drugs on him. In November 2022, he was acquitted of charges of drug possession, but convicted of using forged documents to obtain a Kyrgyz passport. The appeals court ordered Temirov to be deported from Kyrgyzstan.

Temirov is now in Moscow with his relatives, though he was expelled without any documentation (including his Russian passport, reportedly left in Bishkek).

His lawyer, Bakyt Avtandil, told CPJ that their biggest fear is that Temirov, who is of conscription age, could be mobilized to fight in Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Lebanon: A Spiral of Violence

The Middle East remains a perilous region for journalists. In 2021, several were killed or deliberately murdered while reporting, including Lebanese journalist and political analyst, Lokman Slimwas, who was found dead near his car.

According to Reporters Without Borders: “Lebanon is in danger of sinking into a spiral of violence; online attacks and death threats against journalists are on the rise, and sometimes the threats become reality.”

Image: GIJN

Lara Bitar, a Lebanese journalist and editor in chief of The Public Source, has been covering toxic waste inside Lebanon since the country’s civil war — reporting that took on a new urgency in the wake of Beirut’s 2020 port explosion.

But on Friday, March 31, the Cybercrime Bureau, on behalf of the Lebanese Forces, summoned her to appear for interrogation. The Lebanese Forces, a political party that grew out of a wartime militia, was angered by an article from Bitar’s site that drew attention to some of the environmental crimes committed during and after the Lebanese civil war.

This interrogation was disturbing for a number of reasons, but most importantly because the government used a security agency — one that does not legally have jurisdiction over the press — to harass journalists for practicing journalism.

Rwanda: A Government-Dominated Press

After decades of oppression, the Rwandan media landscape is one of the most vulnerable in Africa — and one of the most censored.

According to Reporters Without Borders, in Rwanda, most TV channels are controlled by the government or by owners who are members of the ruling party. Most radio stations tend to focus on music and sports, and avoid other potentially contentious topics. Perhaps the most bleak fact: In a country of 12 million people, there is no longer a single national newspaper.

Image: GIJN

Samuel Baker Byansi, co-founder of the nonprofit site M28 Investigates, spoke with GIJN’s Africa editor, Benon Oluka, about Rwanda’s press history.

During the Rwandan Civil War in the early 1990s, the press was dominated by state media-run pushing anti-Tutsi propaganda, Byansi explained. However, this propaganda was much less sophisticated than the misinformation campaign plaguing Rwanda today. Since 1994, the misinformation narrative has become well-disguised within the popular press, and spread by both intellectuals and pro-government media.

However, there have been recent signs of hope in the country. Byansi cited a 2018 petition related to defamation, where the Rwandan Supreme Court largely ruled in favor of the rights to free expression, among other press freedom wins.

Still, Rwanda has a long way to go.

“Freedom of the press is like other freedoms — no one will give it to you just like that, you have to fight for it,” said Byansi.

Additional Resources

Freedom House: Global Freedom Declines for 17th Year

Lessons Learned from Mexican Investigative Journalist Anabel Hernández

Document of the Day: 2022 World Press Freedom Index

Holly Pate is GIJN’s social media editor. Previously, she was the social media and outreach director of The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism project. She has written for venues including The New York Times and the Capital News Service.

Holly Pate is GIJN’s social media editor. Previously, she was the social media and outreach director of The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism project. She has written for venues including The New York Times and the Capital News Service.