Follow the Money — and Enablers — When Investigating Kleptocracies and Mafia States

What should watchdog journalists do when the country or government they’re reporting on seems to be run as a criminal enterprise?

According to Transparency International’s annual Corruptions Perceptions Index, there are now dozens of countries rated as very or highly corrupt. These de facto kleptocracies — defined as “governments by theft,” that use maximum corruption to loot a nation’s wealth — include more than a half-dozen outright criminal states, which are run purely to enrich a small ruling gang or mafia-style executive family.

While accountability and even personal security for journalists are difficult to achieve in these cases, experts say that simply thinking about these governments as organized criminal enterprises, rather than as repressive political or governing entities, can lead to more effective investigative stories.

That’s because governments that rely on corruption for their existence — similar to the largest conventional criminal empires — require a global network of bankers, lawyers, bookkeepers, and PR agents. This is especially important to recognize, as many of these enablers also operate in democratic countries that do have institutions of accountability. And also because some of the most effective investigations into these thuggish governments use a familiar approach: Follow the money.

In a session on “Criminal States & Kleptocracies” at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) in Gothenburg, Sweden, a panel of veteran journalists who have tackled criminal regimes in Africa, Europe, Asia, and Central America shared key insights on the changing face of government looting, and the methods journalists are using in response.

The panel featured Chikezie Omeje, Africa editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), Drew Sullivan, co-founder of OCCRP, and Peniley Ramirez, executive producer at Futuro Investigates and a former investigative correspondent for Univision.

Distinguishing Between Kleptocracies and Mafia States

Sullivan said criminal states were those with governments solely dedicated to criminal enrichment of a small ruling group, with no interest in the welfare of citizens — and listed mafia-style regimes in Equatorial Guinea, Montenegro, Kosovo, Venezuela, and North Korea as examples. “It’s a state working for one criminal group; a country that’s just being bled for a very small number of people,” he explained.

He said other national governments with mafia aspects of their rule included Russia, Malta, and Mexico.

Kleptocracies, Sullivan said, were far more numerous and typically characterized by autocratic governments that encourage and exploit widespread corruption to stay in power. The panel listed Azerbaijan, Serbia, and Nigeria as examples.

Exposing the ‘Enabler Industry’

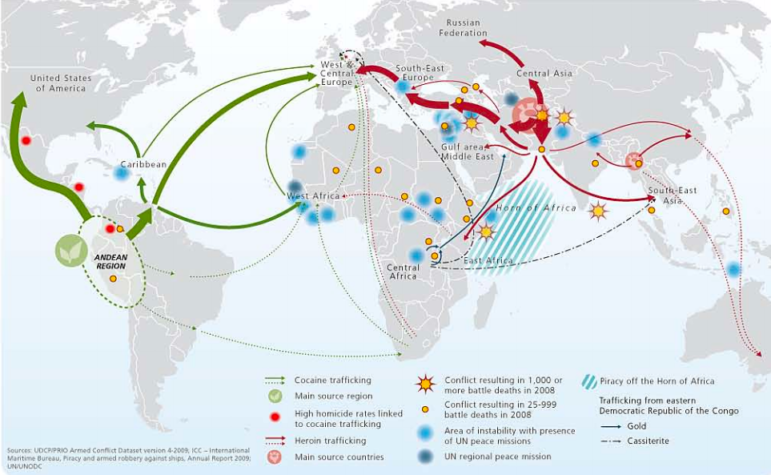

Sullivan said the emergence of “an enabler industry” in the 1990s allowed the globalization of organized crime, the systematic looting of natural resources from the developing world, and, ultimately, the spread of kleptocracy.

“We really need to think about this as an industry, with its own criminal services sector — the lawyers, the registration agents, the banks, the hedge funds; all those who stand to make a tremendous amount of money from organized crime,” he said. Sullivan added that ruling families can easily find expert looting support in the West — but that journalists can also use these money trails to retrace their paths back to the culprits.

“You could go to London and get a high-class lawyer who would protect you and attack media who were criticizing you. You have banks willing to help you effortlessly move money between countries. You could instantly get a global footprint from a registration agent who would allow you to set up offshore companies for tax evasion or customs fraud. You could get lobbyists to buy you political influence. You could buy a security company,” he explained. “One lobbyist can introduce you to all the people you need to know.”

OCCRP co-founder Drew Sullivan (left) talks with GIJN Executive Director David Kaplan at a GIJC23 panel on investigating kleptocracies. Image: Kholikul Alim for GIJN

Effective Methods for Uncovering Enabler Networks

Since these governments are most concerned with hiding and moving a nation’s assets, the panelists said important investigative tools include ship-tracking apps, sanctioned people databases, trusted export databases, money network visualization tools, and hidden money leaks archives such as OCCRP’s Aleph database.

Investigative journalists can expose and, in rare cases, even halt the top-down looting of these economies. In 2017, several investigative newsrooms exposed an intense, systematic effort by foreign enablers to achieve “state capture” in South Africa, in a series called “#GuptaLeaks” that contributed to the removal of Jacob Zuma from the presidency. Sullivan said state capture is the end goal for corruption enablers: the point where they have successfully tilted policies so the spigot of corrupt state contracts is left permanently open, and the officials diverting state resources to their allies are safely beyond accountability.

Peniley Ramirez spent the past decade — in story after story — exposing the fact that a senior Mexican government official in charge of combating the vicious Sinaloa drug cartel was also effectively employed by that same cartel. This year, that “untouchable” official, who had been head of Mexico’s security ministry from 2006 to 2012, was convicted for drug trafficking in a US federal court.

“He was convicted for a continuing criminal enterprise — and yet he was once called ‘The architect of the war on drugs,’” noted Ramirez.

She told conference attendees that she focused on this official’s abuse of government crime-fighting funding, and that much of her evidence came from public records.

“I started by the book: first with global records, then US records, then local, property, and tax records,” Ramirez explained. “I was trying to understand: why is this guy so rich while at the same time he was a public officer in Mexico, where the salaries aren’t so big?”

Ramirez said reporters could still view Mexico as a democracy “because you have not a single family but different families and parties benefiting from power.” However, she added that journalists might need to wait for new administrations to take power before publishing investigations on the crimes of the prior regime.

“But, at the same time, the new party in power will still be dealing with the same entrenched groups, like the Sinaloa cartel, so it is complex,” she added. “Mexico is not like Colombia was, where the narcos [drug kingpins] were trying to be in the parliament themselves.”

However, in other cases, independent journalists have only been able to record evidence of a government’s slide into criminality. One such example is Serbia, which boasted strong accountability institutions and free press laws just 20 years ago, but which the panel now described as a full-fledged kleptocracy.

Identifying a Kleptocracy in the Making

The panel noted that red flags for the slide into state corruption included these tell-tale signs.

- When a president fires an independent anti-corruption prosecutor or disbands or weakens an independent law enforcement unit. This has happened in places like Serbia and South Africa. “When the president of Serbia came into power, the first thing he did was fire all organized crime investigators and prosecutors. Why would you do that unless you were part of a criminal structure?” said Sulllivan.

- When natural resources consistently disappear. Individual cases of large-scale government corruption happen in most countries. But Omeje said the weekly mass-theft of oil from Nigeria — loaded onto on ships bound for Europe — is impossible without criminal government collusion, and that similar, scheduled thefts of resources like timber or gold would reveal the same systemic problem elsewhere.

- When independent media are routinely targeted by major media owned by government allies. “If you look at the state of independent media, you can get a sense of how far along that country is on the path to autocracy and state capture,” Sullivan explained.

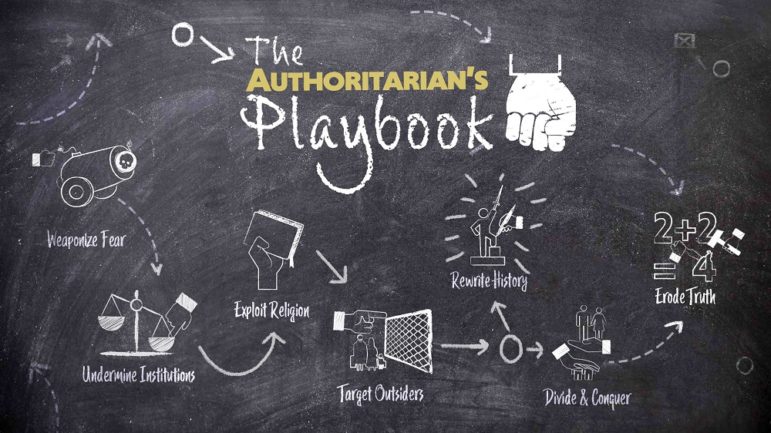

- When strategies from the “autocrat’s playbook” are followed. Session moderator David E. Kaplan — outgoing executive director of GIJN — explained that new autocrats copy the strategies of entrenched dictators, and that journalists can identify these patterns. “First you go after the press, then you compromise law enforcement, then you go after the judiciary and minorities — we have seen this play out in so many countries, where the guardrails of democracy are just not that strong,” said Kaplan. [See the detailed section on “How to Spot Plays from the Autocrats’ Playbook” in Chapter 2 of GIJN’s Elections Guide.)

Omeje said criminals have become even more brazen in their state capture ambitions in Africa.

No Longer Just Pulling the Strings

“What we used to have was criminals who would sponsor a politician, because they themselves felt they were limited by having criminal records,” he said. “They would say: ‘We will sponsor you; we’ll get you the best election PR; we can manipulate elections or use violence to ensure you win. The quid pro quo was: ‘When you’re in power, you must allow us to use the ports to smuggle drugs and other things.’”

Omeje said that, increasingly, criminals are finding protection in direct government power. “Now there is a new method: ‘Why should I make another person a king when I can be a king myself?,” he explained. “They think: ‘I can use my criminal network to run the government,’ in places from Nigeria to Sudan to Zimbabwe.”

He added: “Nigeria is a kleptocracy, but you can’t say it’s a criminal state, because there is still some measure of decency in some of the things the government does.”

After noting cases of money laundering by some well-established banks, Sullivan said reporters should be careful to not discount the possibility that legacy corporations with strong reputations might be active accomplices to state-driven crime.

“They’ll take fines,” he said, “but some of them know it really pays to continue working in this world.”

You can watch the full GIJC23 panel on “Criminal States and Kleptocracies” below.