Lessons from the Pandemic: COVID-19 and Health-Pharma Investigations

Competing claims, a deluge of data, and a new, mysterious virus – the COVID-19 pandemic threw journalists into the fire, confronting the complex arenas of public health and drug development. Even so, investigations during the pandemic have uncovered corruption and fraud, exposed conflicts of interest, and illuminated the influence of pharmaceutical companies, all while educating audiences on vaccines and treatments.

For journalists new to the health and pharma beats, the pandemic has provided valuable lessons on how to sharpen our investigative skills, hold public officials and the pharmaceutical industry to account, and maintain our independence as journalists. But it’s also underscored the damage that misinformation, poor-quality data, and an insufficient understanding of the subject matter can do – and how easy it is for journalists to fall into traps.

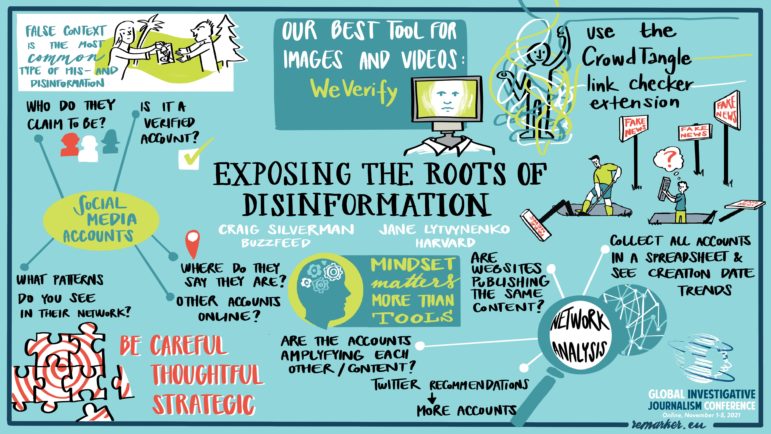

At a panel at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21), Fabiola Torres, founder and director of Peru-based GIJN member Salud Con Lupa, and Catherine Riva and Serena Tinari, co-founders of independent health investigation organization Re-Check, talked about these hazards, sharing tips for digging deeper in future health investigations – and the traps to avoid. Here are seven take-aways from these top health journalists:

The pandemic gives journalists an opportunity to improve health and pharma coverage in the future, panelists said.

1. Learn How Health Systems Work

“You need to know what is normal to say what is exceptional,” said Tinari, giving as an example the extreme fast-tracking of COVID-19 vaccine approvals. The drug approval procedure pre-COVID-19 was a long, time-consuming process, but necessary, explained Riva: “It’s not just bureaucracy, it’s there to protect the patient and the public… a regulatory framework to bring the best knowledge and evidence forward so they can say they have a ratio between benefit and harm that should be favorable for the public.”

There has long been pressure from the pharmaceutical industry to expedite these processes and COVID-19 did just that, squeezing these procedures into a couple of months, added Riva. The effects of this “super-accelerated” approval process in terms of the data collected and the expectations of the industry in the future are ripe for investigation.

2. Understand Drug-Trial Designs – and Their Differences

Drug trials are designed to answer different questions. Journalists need to understand what a particular trial is examining and what it can and can’t tell us about a drug. This context should be reflected in reporting, too. GIJN’s Guide to Investigating Health & Medicine — written by Riva and Tinari — illustrates the different designs of drug trials to help journalists get up to speed with the different methodologies.

GIJN’s guide to Investigating Health & Medicine illustrates the different designs of drug trials to help journalists cover public health.

Look out for “red flags,” for example, when the design of a trial is already skewed toward a particular result, or where the sample size or the size of the results are not as significant as the research claims, said Torres.

3. Watch for Science and Regulation by Press Release

A new vaccine or drug is announced as market-changing by a press release? Check the source, what their agenda is, and the details of any trials – their duration, their focus, and what specifically has been tested.

See, for example, Re-Check’s analysis of a November 2020 press release from Pfizer and BioNTech, claiming their new vaccine would protect 95% of people against COVID-19 – a claim widely reported by international media. “We had no data, we just had Pfizer’s word for it and were told we should believe them,” said Riva. “It’s not enough to base conclusions and make public health decisions based on the communications of a pharmaceutical company.”

4. Understand the Impact of Emergency Use Approvals on Trial Data

The impact of Emergency Use Approvals (EUAs) for COVID-19 vaccines on the quality of drug trial data suggests that wider use of “super accelerated” approvals for new drugs “might be a bad idea,” said Riva. “Once you open that door, it’s very difficult to say to other pharmaceutical companies that their products should be approved in a regular way… It becomes very difficult to justify.”

These expedited trials last just months and once a drug is on the market, there is no longer a control group. “The data we obtain in trials is of a higher quality than what you can collect in real life,” she explained. “In real life, you have a lot of confounding factors… a lot of background noise, whereas when you study a drug in a clinical trial you have rules.”

5. Investigate Conflicts of Interest

Public officials or health workers with conflicts of interest or influenced by drug companies are a rich stream of stories for investigators. A prime example: Salud Con Lupa’s Vacunagate investigation into political corruption linked to secret vaccine doses offered by a Chinese pharmaceutical company. Checking for conflicts and finding independent sources can help establish your reporting as transparent and free from influence.

Check if sources or subjects have conflicts of interest by looking at disclosures in medical journals and journals shared by the International Society of Drug Bulletins, the registration details of medical patents, and also social media profiles. Some countries have databases recording financial relationships between health officials and workers, and the pharmaceutical industry, such as the Open Payments database in the United States.

“Try to identify someone who is not involved in that investigation, knows that field and topic, but is an independent expert following this field,” said Torres.

6. Reframe Your Reporting

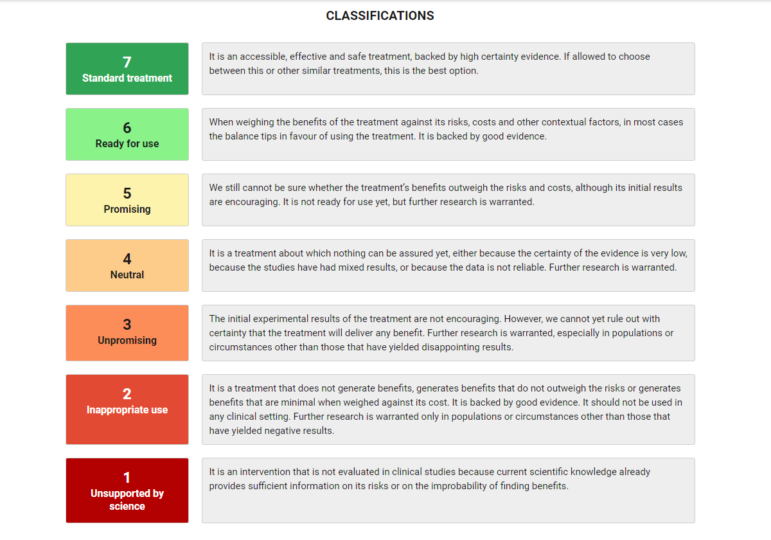

“The most important question to consider in covering health is how it will affect readers’ lives right now,” said Torres. This is a useful strategy when faced with a deluge of new data, research, or leads for investigation. Salud Con Lupa’s tool analyzing the most-discussed COVID-19 treatments has allowed readers to check 42 drugs or remedies ranked on a scale from “unsupported by science” to “standard treatment.”

7. Look at What’s Not Reported

Drug and vaccine development, the approval process, and the science of COVID-19 have been fast-moving and have often kept the media occupied with the latest updates. Looking at what has not been reported is an opportunity for journalists — during this pandemic and in the future. “For example, we still don’t know enough about the interests of doctors, scientists, and academics who advise the government,” said Torres.

Retracted claims, whether centering on the efficacy of a treatment or vaccine development, have gone under-reported, too. A handy place to start is The Retraction Watch, a database, and blog, which documents retracted research papers and contested research.

For more expert advice, GIJN’s Investigating Health and Medicine Guide, by Re-Check’s Riva and Tinari, is available in seven languages.