Everyone needs an editor, and for investigative reporting, the stakes are even higher. Image: Wolf France for GIJN

8 Tips for Upping Your Game as Investigative Editor

“Everybody needs an editor.” This was the mantra that veteran Associated Press investigative editor Ron Nixon asked the audience to repeat during a session at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) on editing investigations. Why? Because as the panelists explained, great investigative editors make stories stronger, protect and motivate reporters, and make investigations more efficient.

“What makes a good investigator is not necessarily what makes a good investigative editor,” said Drew Sullivan, publisher and co-founder of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). For Sullivan, the difference is both in what editors are tasked with and their approach to the job. It’s an investigative editor’s job to make the reporter a success, to mentor them rather than be their boss, and to take the blame if anything goes wrong.

Investigative editors are not allowed an ego, he said: “You have to give away all the credit.”

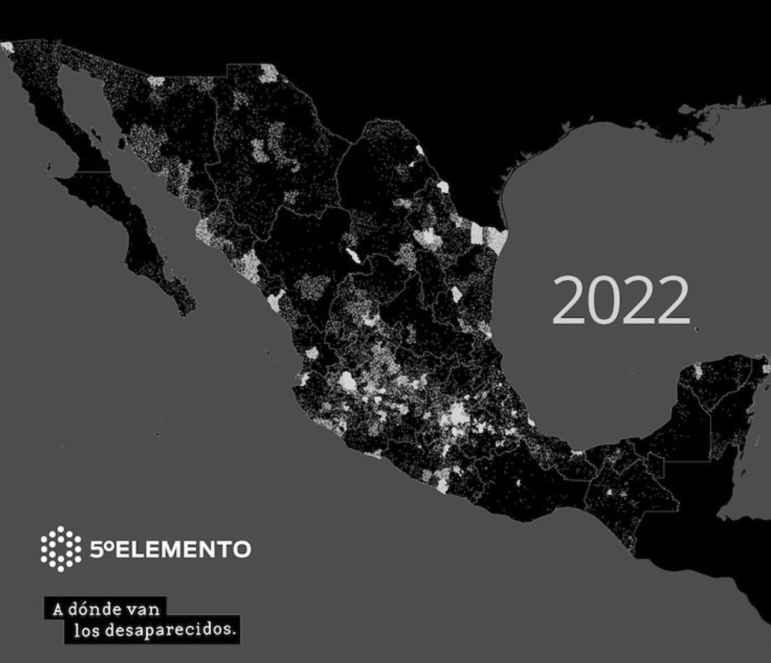

From story pitch to post-publication, here’s first-hand advice on how to be a great investigative editor from OCCRP’s Sullivan, Nixon, who is vice president of news and head of investigations, enterprise, partnerships, and grants at AP; Alejandra Xanic, editor and co-founder of Quinto Elemento Lab, a nonprofit in Mexico that publishes investigations and trains new investigative editors in Mexico, El Salvador, and Brazil; and Vinod K. Jose, the former editor of India’s The Caravan.

1. Identify the Story

“When you’re working across cultures and collaborative projects, there’s often quite a different idea of what makes a good story,” said Sullivan. A good investigative story should be focused, achievable, important, appealing to readers, potentially impactful, and not too expensive, he said.

AP’s Nixon said he deploys conceptual editing at the beginning of an investigation and will sit down and ask reporters to tell him a story. “People start to list facts; I don’t want facts, I want the story,” he said. “It helps you conceptualize where you are going. They’ve got a bunch of facts but it’s up to you as an editor to draw the story out of them.”

2. Chart a Good Investigative Plan

Sullivan said an investigation should not move forward until the critical information needed to confirm the story has been identified. “Force reporters to prove the information that meets the minimum story and do nothing else before that,” said Sullivan. It’s an editor’s job to keep asking that question and stop reporters from jumping ahead to work on characters and interviews, for example.

“How you prove that critical information dictates what you can say in that story and how you can tell it,” he said.

3. Keep the Story Focused

Ask reporters what the thesis of their story is to help them focus. Xanic gets reporters to note this down and post it on their desktop as a physical reminder of the story’s focus, while accepting that this may change as it develops.

Talking to reporters regularly and repeatedly will help them figure out the crux of their investigation and the process, said Sullivan: “Reporters think by talking. You [the editor] are there to listen… Prompt them — that’s where they learn and understand their story.”

4. Get Organized

Reporters often dismiss a “boring but important” aspect of great investigative editing — organizing, said Xanic. Getting reporters to organize their material as they collect it and sharing this with editors is crucial, and means that editors “know sufficient detail to ask intelligent questions and make reporters see the blind spots,” she said.

5. Create Living Documents

Xanic recommends that editors create a series of living documents to help. This should include a chronology of the investigation — a timeline of events and inquiries that also provides an index of all other documents and materials involved.

In addition to physical or digital files documenting evidence in the investigation and a file of any Freedom of Information requests, editors should encourage reporters to write notes summarizing what they’ve learned from interviews and at regular points during the reporting. This should include new questions that have arisen and helps editors to stay close to the reporter and the story, and to ask questions or make reporting suggestions.

Nixon agreed, saying reporters should annotate every document and interview they collect: editors need to be able to see or hear the context of a quote or a statement when editing the final investigation.

“Make sure your notes from conversations with reporters are organized,” Xanic added. “Editors can remember things that reporters have forgotten.” Editors will also need to create and update a schedule and budget for the investigation.

6. Line Edits

Whether it’s line-by-line for a text story or frame-by-frame for a video, this is how detailed your editing for an investigative story needs to be. “You’re prosecuting every single fact,” explained Nixon. “It’s not the big things that will trip you up; it’s always the little things.”

It takes a long time but is preferable to a correction or a lawsuit, he said. Reporters can aid this process by documenting and providing evidence for all claims and facts cited in a story.

7. Know When to Say Stop

Reporters can spend an incredible amount of time going down a rabbit hole — an editor needs to stop them from wasting time. They also need to be the ones to end an investigation if a story isn’t working, said Sullivan: “You need to be the adult in the room… It’s important that you don’t keep throwing good money after bad, you have to kill a story.”

8. Protect Your Reporters

Editors are responsible for reporters’ safety during an investigation and need to recognize danger, burnout, and other problems.

“Journalists avoid concerns about safety because it’s a scary thing. Consequently they don’t want to deal with it, so you have to,” said Sullivan. Set protocols for how the reporter might approach a story or approach sources and ask questions constantly to assess the risks and any dangers they might encounter during the investigation.

Editors should also “take the blame,” said Sullivan, to shield reporters from legal threats or concerns from newsroom management: “Keep the reporters safe and sheltered so they can focus on what they need to do.”

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the Guardian, BBC, Euronews, and others. She is a regular journalism trainer for the Thomson Foundation and Thomson Reuters Foundation and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms. You can find her work here.

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the Guardian, BBC, Euronews, and others. She is a regular journalism trainer for the Thomson Foundation and Thomson Reuters Foundation and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms. You can find her work here.