Image: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Revised Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Where to Begin

Read this article in

Chapter Guide Resource

Revised Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Where to Begin

Chapter Guide Resource

Revised Elections Reporting Guide for Investigative Reporters: New Digging Tools

Chapter Guide Resource

Revised Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Preparing for Elections

Chapter Guide Resource

Revised Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Investigating Candidates

Chapter Guide Resource

Revised Elections Guide for Investigative Reporters: Political Messaging and Disinformation

Editor’s Note: This reporting guide has been updated and revised for the 2024 election cycle. It was originally published in 2022 and the previous version of this chapter can be read here.

“We will know whether democracy lives or dies by the end of 2024.” This comment by Nobel Peace Prize laureate and investigative journalist Maria Ressa to Politico underlines the stakes behind elections around the world in 2024.

Certainly, global elections in the year ahead — including presidential, legislative, and regional polls in at least 60 countries — will affect more citizens than in any previous year, and will likely reset humanity’s liberty compass for years ahead.

Elections face increasingly common threats, including disinformation campaigns, foreign interference, voter suppression, rising authoritarianism, campaign corruption, minority disenfranchisement, and violence and intimidation.

Meanwhile, the state of democracy around the world has steadily eroded in the past two decades as “elected autocrats” consolidate their power through corrupt alliances with oligarchs and fellow authoritarians, misinformation and hate speech is prioritized over facts by social media algorithms, and historically democratic governments use xenophobic fears and conspiracy theories as pretexts for suppressing civil liberties and the press. Ominously, the world has also witnessed the invasion of a major Eastern European democracy — Ukraine — by Russia, an autocratic regime, as well as the opposite case: the invasion and occupation of an independent territory by Israel, a democracy.

The health of global democracies have declined for 17 straight years, per the 2023 Freedom in the World report. Image: Freedom House

However, investigative reporting has consistently served as an effective check against election abuses, and, yes, has even played a direct role in saving democracies. In 2018, an investigative series collectively known as #GuptaLeaks led to the ousting of a corrupt president and his enablers in South Africa, following a revelation by several collaborative newsrooms of a vast “state capture” corruption scheme that directly threatened that nation’s democracy. This also illustrates the kind of specific impact investigative newsrooms can have in parliamentary democracies — where citizens vote for a party rather than a president — in which relentless investigative revelations place public pressure on the ruling party to get rid of corrupt members and institute accountability reforms.

While each nation’s election has unique and often rapidly-evolving rules, this five-part guide is designed to set out some of the common threats (and therefore some of the best investigative reporting topics) facing many electorates, as well as some innovative tools and techniques to expose the bad actors behind them. Of course, many countries, such as Russia, Iran, Venezuela, and Algeria, run purely sham elections, where repressive laws and patently unfair political playing fields make rapid accountability and opposition challenges all but impossible. But leading editors say watchdog reporters should still relentlessly expose the mass abuse of citizens’ rights and connect voters with critical information — sometimes, with the use of VPNs, new censorship circumvention apps, or shortwave radio. Remember that the foreign enablers of autocratic regimes are often subject to accountability mechanisms in their own countries, and offer a rich source of investigative topics.

More than five dozen countries have scheduled elections for 2024, for offices of executive (red), legislative (blue), executive and legislative (purple), referenda (yellow), and referenda, executive, and legislative (black). Image: Wikipedia, Creative Commons

Major elections in 2024 include potentially seismic votes in Mexico, South Africa, Pakistan, Romania, and India, as well as the European Parliament and also — potentially — the United Kingdom, and even post-coup countries in Africa, like Mali and Chad.

However, the most globally impactful of these will occur in the world’s oldest democracy, the United States, where the threat of populist autocracy, political violence, and minority rule looms large both for citizens and for other nations that look to it for their governance inspiration or alliance. Given that former President Donald Trump — who has been indicted under numerous criminal charges, including an attempt to subvert US democracy — is highly likely to be chosen as one major party candidate, journalists will need additional tools to dig into issues far beyond a traditional political campaign. For instance, watchdog reporters need a tool to keep track of all of these parallel processes in a likely populist campaign from the courthouse steps. (One crucial resource will be the Lawfare blog, which provides a daily track of both the many criminal trials, as well as several court challenges to Trump’s eligibility to be on the ballot in several states. Another is the constantly updated Democracy Toolkit, a major investigative resource by Hearken, Election SOS, and the Center for Journalism and Democracy, which includes a database of expert sources, and has relevance to elections in many countries.)

Traditional political coverage and the already overused horse-race approach are wholly inadequate for exposing and measuring election threats, or for tracking the bad actors behind them. Instead, independent media and watchdog journalists need to dig beneath the surface of increasingly precarious elections, while also protecting their information, themselves, and free expression itself from multi-pronged assaults by anti-democratic interests. To do this, they require courage, planning, collaborative support, courageous human sources, and new, innovative tools to deal with these threats.

How to Have Investigative Impact in Polarized Societies

In politically polarized societies from India to South Africa and the US, investigative reporters worry that even major scoops with verified evidence of election wrongdoing might not “move the needle,” or have any impact at all. That’s because they recognize a global trend of declining public trust in journalism, and because of the problem of confirmation bias, in which audiences automatically favor facts that support their existing views, and tend to discard those that challenge those opinions. But research and the insight from expert sources show that the following techniques should be effective in any country in getting investigating findings to break through tribal “information bubbles.”

- Turn your data findings into infographics. Research shows that voters like to “discover” the truth from clearly displayed data, rather than being told what it means in text or speech. As veteran journalist Amanda Ripley told GIJN: “One short term solution is: just do an infographic. With a really good graphic, it feels that you are coming to the conclusion about the issue or the candidates yourself.”

- Collaborate with other newsrooms — including rival and foreign outlets. It’s harder to dismiss an election investigation as partisan or the result of planted propaganda if several outlets arrive at the same core finding. Collaborations also benefit from more diverse sources and skill sets — and each story can amplify the others through cross-promotion.

- Include a prominent “Why we chose this investigation” explainer box in your story. Media experts stress that why-we-did-this explainers are effective in boosting audience trust, in combating false equivalence, and in showing voters why the issue should concern them.

- Be intentional about listening — both to sources and whole audiences. Experts say that newsrooms should actively ask their audiences: “What else would you like us to find out for you?” They say that effective listening by reporters can include sit-downs with diverse communities, and asking open-ended questions rather than leading questions.

- Avoid a scornful tone. Headlines sometimes feature dismissive words like “surreal,” bizarre,” and “absurd” about partisan behavior. Research indicates that this tone can alienate potential audiences from a brand entirely.

- Access young voters with alternative media formats. Investigative podcasts and “scrolly-telling” stories designed for smartphones are among those formats shown to have an impact with young citizens who have disengaged from traditional media.

- Correct the vast tribal “meta-perceptions gap.” Across the world, research shows that partisan groups are generally hated far, far less by rival supporters than they think they are. Journalists have an opportunity to make major inroads into often wildly false perceptions of rival attitudes, with infographics and voter interviews. (One research study in the US showed that 49% of Democrats and 47% of Republicans believed members of the other party disliked them simply because of their political affiliation, when, in fact, only 18% of each party actually disliked members of the other.)

A campaign billboard for Hungary’s ruling Fidesz Party, featuring Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (right), during the country’s 2022 parliamentary elections urges voters “Not Back, Let’s Go Forward!” Image: Shutterstock

The “us versus them” problem lies primarily with unscrupulous leaders and their enablers and ideological allies, rather than partisan voters. Following what many scholars called the “third wave of democratization” in the 1970s and ‘80s, researchers are now warning of a “third wave of autocratization,” in which authoritarian leaders learn tactics from each other to erode democratic institutions, enact repressive laws, outsource violence and intimidation, and control or pollute the information landscape.

These same authoritarians can also create unfair playing fields for the opposition. For example, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán — whose party, Fidesz, won parliamentary supermajorities in 2010 — has radically rewritten his country’s constitution, giving him and his party an easy path to rigging future elections in their favor. But research shows that even in countries where authoritarians eke out narrow election victories — as with Poland — democratic institutions can be gradually eroded, step by step, in a way that generates similarly drastic results. Investigative journalists can catch them in the act.

RISE Moldova Case Study: A Methodology for Election Scoops

Reliable global and local databases are excellent resources for triggering new questions, finding connections, and checking facts. However, Vladimir Thorik, Russian-language editor of the investigative outlet RISE Moldova — a GIJN member and Eastern European affiliate of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) — emphasizes that most major scoops about election misconduct begin with human sources or leaks, and end with a combination of database mining, social media searches, and open source tools.

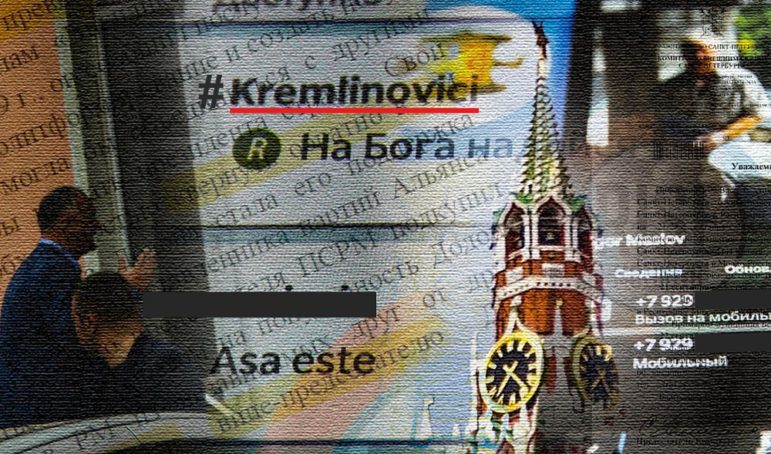

In 2020, Thorik and his team’s “Kremlinovici” investigation followed a path that represents a classic watchdog methodology that applies almost anywhere. It began, he says, with a leak from an anonymous source who respected RISE Moldova’s prior in-depth election reporting. This initial leak was followed by interviews with developed sources, and verified via a database known as the Chernov Archives, as well as by collaborative reporting with the Russian Dossier Center.

Beginning with a leak, the RISE Moldova team connected the 2020 re-election campaign of Moldova’s then-president to direct involvement from the Russian intelligence services. Image: Screenshot, RISE Moldova

Thanks to this comprehensive process, RISE Moldova exposed close links and coordination between the re-election campaign of Moldova’s then-president and Russian intelligence services. In addition, it documented violations of election laws, found several business links between the president’s family and Russian corporations, and identified eight mysterious visitors to the presidency and ruling party headquarters as “election technology advisers” that had been dispatched from the Kremlin. RISE Moldova even showed how some domestic speeches and campaign slogans were cooked up in a secretive Russian foreign influence unit.

Thorik’s series represents a useful case study to follow for election scoops in 2024 and beyond. It includes tips like:

- Develop human sources around campaigns, civil society organizations, and law enforcement.

- Investigate candidates’ financial and political connections, using social media and databases like OpenCorporates and Aleph. RISE Moldova used the Chernov Archives database, leaked from Russian sources.

- Identify election threats — such as Russian interference, in this case — flagged by your sources, and actively search for signs of anti-democratic assault.

- Attract leaks from whistleblowers with consistently courageous political reporting, and offer tipsters more confidence by using encrypted channels like Protonmail for documents, and Signal for communications.

- Employ social media search tools to learn the political conversations, misinformation, and potential impacts triggered by the action you’re investigating.

- Collaborate with newsrooms and nonprofits that have better sources or deeper insights into the troubling influencers you uncover. RISE Moldova collaborated with the Russian Dossier Center to dig into the Kremlin department responsible for influencing foreign elections.

- Train yourself on election rules — Moldovan law, and the Central Electoral Commission, in this case — and check for possible rules violations.

- Hit the streets to conduct in-person interviews. and note any possible inside sources close to the campaigns at rallies and public events — including drivers, cooks, and campaign photographers. Take photographs of unfamiliar faces interacting with campaign staff for later analysis.

- Use open source tools to identify and track the protagonists. Thorik’s team used tools like PimEyes and Findclone to identify outside “election consultants” whom their sources didn’t recognize.

- Call on experts and data analysis to demonstrate how that misconduct may have altered the election, or how similar tactics distorted previous elections in other countries.

“For a big revelation in an election, you need primary information that you can’t find in any database, which means well-placed human sources or a leak,” Thorik explains. “But you do need those databases to fact check and dig further, and tools to zero in on individuals.” For instance, the initial tip Thorik received revealed the online username “Kremlinovici” that Moldova’s then-president used for strategic communications, which then guided the RISE Moldova team’s targeted online searches.

But how should leaked materials get into reporters’ hands? “Personal transfer of leaks is good because it eliminates a digital trail,” Thorik advises. “But I recommend not receiving leaks yourself, in person, but rather through an intermediary, as direct contact could endanger the source.”

Besides revealing alarming foreign meddling on behalf of a pro-Russian candidate, Thorik’s investigation also proved that Moldovan laws were violated because outside consultants hadn’t registered with the Central Electoral Commission. He also showed how the campaign tactics of the incumbent changed drastically in the wake of that Russian advice.

What You’ll Find in this Serialized Guide

While election rules and conditions are unique in every country, this revised and updated GIJN guide is designed to offer a broad array of tools, techniques, and resources — beyond the primary local sources you find — to help watchdog reporters dig into almost any election. For instance, there are surprisingly simple online techniques for identifying and connecting people behind fear-mongering campaign sites, and open-source tools now exist that can search political ads on Facebook; track police audio chatter; dig into extremist and anti-democratic social media channels; track illicit campaign financing; and automatically filter mountains of data.

In this big-picture introduction, we will preview the more technical, serialized chapters to follow, and highlight an example methodology for election scoops.

New Election Digging Tools and Strategies

We asked leading journalists and elections experts around the world for the best new tools and techniques for reporters investigating elections. In this chapter, we share some reliable digital tools that can help most campaign investigations and a list of useful strategies to consider. We also provide an in-depth profile of our featured election digging technique, known as “the Pub/UA method.” This technique can identify hidden individuals behind election-related websites, which requires no digital skills more advanced than “Control-F” keyword search commands.

Preparing for Elections

In this chapter, we list tools and resources for understanding the rules of elections, and how to keep yourself, your sources, and your data safe, while finding leads and sources.

We also quote experts on the necessary strategies that flow from the fact that most national elections are not national at all, but rather focused around a handful of places and issues. For instance, deep political polarization in the US means that, almost certainly, the results from only seven of its 50 states will determine the next president — which means that reporters can focus on corruption, disinformation, and ‘dirty tricks’ concentrated in those few states. We’ll also list election trends to investigate, including the increasingly popular “elected autocrats’ playbook.”

Investigating Candidates

It’s important for reporters to assume they know nothing about politicians who stand for national office. Here, we share tools for uncovering candidates’ online histories, hidden assets, and contacts for people who really know them. We will also share a methodology for performing due diligence on candidates’ backgrounds, using a revealing Brazilian case study.

Investigating Political Messaging and Disinformation

Where are influential election conversations actually happening? Who are the political ad donors and the disinformers, and how can they be identified? In this chapter, we’ll share step-by-step methods for digging into platforms like Telegram, WhatsApp, and Twitter (now “X”), where citizens discuss everything from important policy issues to bizarre conspiracies to plots to violently overturn elections.

Rowan Philp is a senior reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a senior reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.