Editor’s Pick: 2021’s Best Investigative Journalism from Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus

Read this article in

The past year will be remembered for its constant attacks on freedom of speech and the press, as well as restrictions on the rights and freedoms of journalists themselves. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a modern-day record for the number of imprisoned journalists was set in 2021, with at least 293 now behind bars.

The situation among the countries of the old Soviet Union — the former communist nations in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus — is particularly worrisome. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists, there are at least 31 media staffers among political prisoners in that country alone. In Russia, an official campaign by the Ministry of Justice designated independent media and investigative journalists “foreign agents” at an astonishing rate: from only 17 at the start of the year to 111 by the end of December. In addition, the Russian government declared the investigative media outlet Proekt an “undesirable” organization.

Tarred with these pejorative labels, independent media and reporters in Russia are not only beset with many additional bureaucratic burdens, by law all messages on their websites or social media must be accompanied by a warning about their foreign agent status. Even worse, authorities raid newsrooms and homes of reporters and their relatives, summon them for interrogations, and, under the threat of arrest and prosecution, force them to leave the country and work in exile.

And yet, despite all this, solidarity among journalists in the region is growing. Our list of the best investigations of the year reveals that more and more cross-border, joint investigations are being carried out. It is no coincidence that, in its forecasts for journalism for 2022, a NiemanLab post predicted barriers that prevent collaboration between newsrooms across the globe will fall for good, and former competitors will begin to build long-term, mutually beneficial relationships.

Independent reporters in the region have never had it easy, but today they are showing a toughness and determination that should be envied around the world. The award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Novaya Gazeta editor Dmitry Muratov will likely give a needed boost to these journalists on the front lines. Here are examples from gutsy journalists who refuse to back down, even under the worst kind of pressure.

Putin’s Palace (Russia)

This January 2021 investigation by the nonprofit, anti-corruption organization FBK — founded by Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny — exposed a massive abuse of public funds to build the vast, $1.35 billion palace complex for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Although not a traditional media organization, Navalny’s group did a world-class piece of investigative journalism. Investigators obtained information from the Stasi archives and construction documents from land registries to reveal a complex web of Putin’s friends and their associations with companies supporting the palace. They used drones, builder testimonies, and many other sources to offer a behind-the-scenes, 3D tour of one of the most expensive and secretive buildings in Russia. The leader of the investigative team, Maria Pevchikh, went into more detail about the tools and methods of this investigation in an interview with GIJN.

FBK’s two-hour video exposé received more than 108 million views on YouTube within a week. In the same week, Navalny — who tried to run against Putin in 2017 but was barred from the election — was jailed for two years on charges widely condemned as political payback from the Kremlin. Navalny’s group was subsequently labeled an extremist organization in Russia and dissolved after a court decision in June 2021.

What Are Former Ukrainian Special Police Doing in Belarus? (Belarus)

Denis Ivashin from the Belarus newspaper Novy Chas conducted this investigation into former officers of the Ukrainian “Berkut” special police unit, who have joined the Belarusian interior ministry in dispersing rallies and tracking opposition activists in Minsk. Using open-source reporting, Ivashin revealed the names of the officers who could be implicated in the shooting and beating of civilians during the “Revolution of Dignity” in Ukraine. Some of them, according to the story, may have also illegally obtained Belarusian citizenship.

After the release of the third part of this investigation, Ivashin was arrested by the Belarusian KGB for “interfering with the actions of an employee of the internal affairs bodies.” Six months later, a second accusation was added to the first charge: “treason to the state.” His reporting on the issue is now blocked in Belarus and is available only through the Internet archive and in Ivashin’s interview with Russian-language TV channel “Current Time.”

Four Killers, Three Cops, and a Drug Baron (Ukraine, Serbia)

In this cross-border investigation from two GIJN member organizations, Ukrainian journalists at Slidstvo.Info and Serbian journalists from KRIK dug into an assassination attempt on the Balkan drug lord Radoe Zvitser, which took place in the center of Kyiv in the spring of 2020. In their investigative documentary (available in Ukrainian, with English and Russian subtitles), the reporters reconstructed the chronology of the crime and named key persons potentially involved to show that this attempted murder was only one episode in a long and bloody war between two drug clans. According to the story, the probable killers were likely assisted by three Ukrainian police officers — one close to the National Police leadership — who allowed them to cross the border and enter Kyiv for their planned hit.

Secret Uzbek Billionaire (Uzbekistan)

This investigation, by Radio Ozodlik (the Uzbek service of RFE/RL), focuses on one of the new Uzbek oligarchs. This young billionaire from Fergana, a regional capital near the Kyrgyzstan border, became mysteriously rich soon after he married the second daughter of the country’s then-prime minister, Shavkat Mirziyayev, in 2007. Radio Ozodlik journalists report that a company linked to the son-in-law of Mirziyayev, who became Uzbekistan president in 2016, allegedly received tens of millions of dollars from a government welfare fund.

Pandora Papers

In 2021, 600 journalists, coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), uncovered the offshore deals of more than 130 billionaires, 35 world leaders, and 330 officials around the world, as part of the Pandora Papers. Within the region, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, IStories, and Slidstvo.Info all contributed to exposés based on this massive leak.

Among the notable names in these documents: the family of the President of Azerbaijan, found to have real estate holdings in London worth $694 million; the unofficial wife of the former President of Kazakhstan, who allegedly earned $30 million in offshore transactions; members of the entourage of Russian President Putin; and officials from inside Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s inner circle.

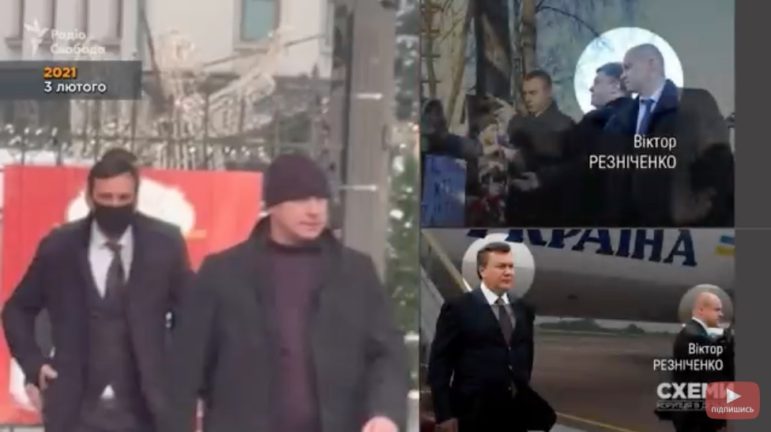

Mr. Who? (Moldova, Ukraine)

This story by the Moldovan journalism network Rise Moldova and Ukrainian program “SCHEMES: Corruption in Details” (a joint project of Radio Liberty and the channel UA: First) began with a photo capturing an unknown man being escorted to the office of the Ukrainian president by one of the leader’s ex-bodyguards. Having become interested in this mysterious visitor, Ukrainian journalists, collaborating with Moldovan colleagues, revealed a bizarre, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction detective story. According to their reporting, the visitor was a man who had been sentenced to 11 years in prison for theft and fraud in Moldova, changed identities at least four times, and survived his own fictitious death. They also found that he had sought election to the Ukrainian parliament, but was banned from running after being discovered on an international wanted list, and later lobbied three presidents for a top Ukrainian oligarch.

Inside Wagnergate (The Netherlands, Russia)

An international team led by Bellingcat’s lead Russia investigator, Christo Grozev, explored a brazen Ukrainian sting operation, which tried to ensnare several dozen Russian mercenaries who were believed to have previously committed various crimes in eastern Ukraine. The daring plan failed at the final stage, in July 2020.

After conducting dozens of interviews, and analyzing and verifying thousands of pages of electronic documents and hundreds of hours of audio recordings, the authors meticulously described the Ukrainian intelligence operation. The reporters detailed how the online sting collected data, created a fake private military company, recruited Russian mercenaries under the pretense of protecting oil wells in the Middle East, and then planned to transport the military personnel through Belarus to Ukraine, at which point they would be arrested. Instead, Belarusian authorities announced the arrest of the 33 mercenaries in Minsk.

The remarkable techniques used by Bellingcat and The Insider during their work on this story were described by Christo Grozev in a separate article.

The Passport Business (Tajikistan)

This Radio Ozodi exposé revealed the rampant abuse of Tajik passports by migrant workers and others to regain entry into Russia after being deported from that country. According to the report, it’s surprisingly easy to obtain a new passport in Tajikistan simply by changing one’s name. Though the name change process should be complex, according to Tajik law, and can take at least three months to complete, sources told the reporters that, for a fee, a person could obtain a new official name in just 10 days. The story even included a phone transcript of a journalist being walked through how to expedite the fake name process — with an implied bribe of roughly $500 — by a government official. In total, Radio Ozodi found through government reports that an astounding 235,000 people had received new names in Tajikistan since 2014.

Additional Resources

What to Do When Authorities Raid Your Home

What Journalists Can Learn from Navalny’s Investigative Team in Russia

My Favorite Tools with Russia’s Roman Anin

Editor’s Pick: 2020’s Best Investigative Stories in Russian and Ukrainian

Nobel Winner Muratov: Be an Investigative Reporter, and Fight for a Better World

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian-language editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB, and has participated in SCOOP’s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English, and Greek.

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian-language editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB, and has participated in SCOOP’s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English, and Greek.