Asset Disclosure

Read this article in

Required disclosures by public officials about their income and assets can be invaluable to investigative journalists. And information about wealth and its sources can play a vital role in uncovering corruption.

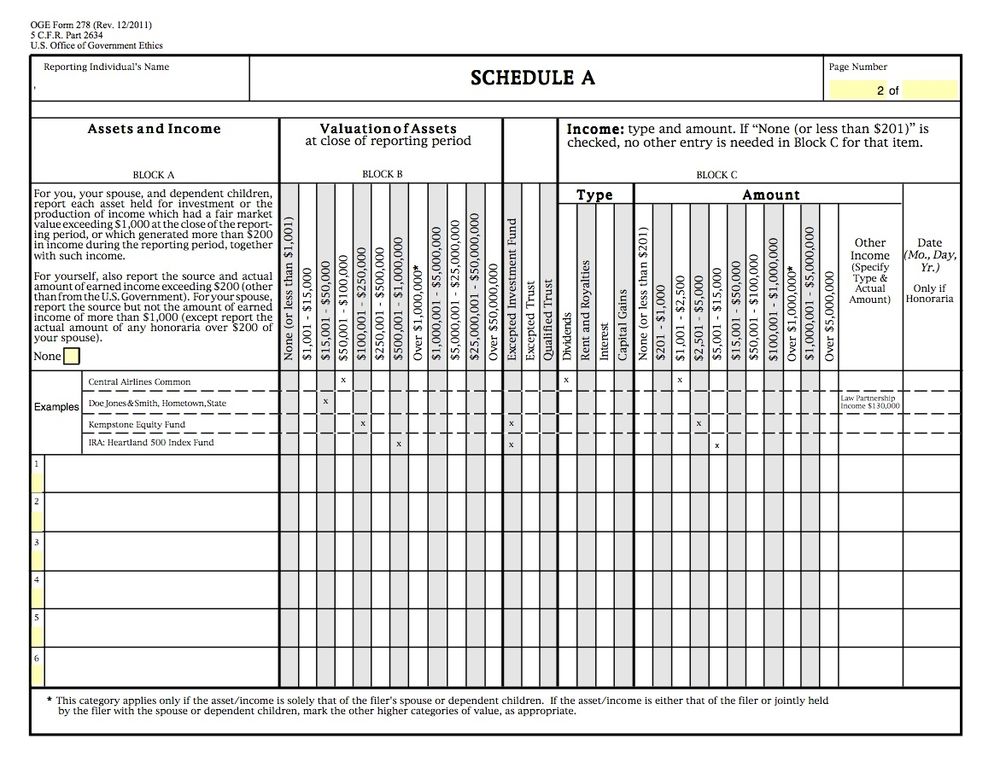

US Asset Disclosure Form example. Income and asset disclosures by public officials, now mandated in some 160 countries, can play a key role in investigations of corruption and public accountability. Image: Screenshot

Official filings are often the starting point for classic follow-the-money stories. However, disclosure laws have gaps, so the public records don’t always reveal the whole truth.

Officials sometimes fail to report all they are supposed to, and reporting reveals their actual financial resources and where it came from. Research may uncover conflicts of interest. Fact-checking and probing is necessary.

In this guide, GIJN has compiled a wealth of resources on where to find asset disclosures, and what to look for.

Who’s Covered by Asset Disclosure Laws?

Disclosure laws typically require that specific public officials declare their financial and business interests.

These people are referred to as “politically exposed persons” (PEPs).

According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a PEP is “an individual who is or has been entrusted with a prominent function.” A PEP could be a head of government, a board member for an institution such as a central bank or supreme court, or even the family member of a high profile individual. They also could be judges and members of parliament. As a result of their prominent positions, PEPs pose a higher risk for engaging in money laundering activities, bribery, or corruption. But what or who constitutes a PEP can vary slightly from country to country, so it’s imperative reporters understand the applicable legal definitions in each jurisdiction they are covering.

OpenSanctions has a free, fully searchable list of PEPs, which is regularly updated. Its database includes over 190,000 politicians, 28,000 close associates, 120 people linked to terrorism, and even five individuals listed as “spies.” Another source for the data is profiles of PEPs from Wikidata —which tracks when individuals are listed as working in prominent positions around the world — as well as Forbes 2023 List of Russian Billionaires (in Russian).

PEPChecker also offers a list of over 1,000,000 politically exposed persons from more than 240 countries and territories, and users can conduct a limited number of searches free of charge. Like OpenSanctions, they also incorporate sanctions from the official lists of relevant authorities. In PEPChecker, searching is done by individual name.

What Disclosures Are Required?

There is international consensus that countries should require asset disclosures.

More than 160 countries had financial disclosure systems according to a 2017 World Bank report. However, the bank has since discontinued its database on disclosure systems and no full listing exists.

National laws vary greatly in the detail of disclosure required and how frequently the reporting must occur. Also of importance is whether compliance is monitored and enforced. So a clear starting point is to learn the nuances of the individual disclosure laws.

In the UK for example, declarations by politicians include employment and earnings; gifts, benefits, and hospitality received; land and property owned; family members employed and paid from parliamentary expenses; and shareholdings in companies.

In Georgia, disclosures include real estate, vehicles, income, and the individual’s financial wealth in banks and credit institutions within the country and outside.

However, it is very rare for a disclosure law to cover all bases and there are many national anomalies.

For example, gifts from immediate family members do not have to be declared, according to a comparative review of nine countries by the Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity. In Hungary, loans from individuals do not need to be declared. In North Macedonia, asset declarations are removed immediately after a PEP leaves office.

Transferring assets to other parties or having purchases made in their name are classic ways to avoid scrutiny. And because these disclosure regimes are famously full of loopholes, there’s an opportunity for journalists to expose their weaknesses.

Note: disclosure of campaign contributions is typically handled differently, in separate databases. But such donations are obviously of potential relevance when examining the actions and connections of politicians.

Where to Find National Asset Disclosure Databases

Initial research at the national level is necessary to find out whether asset disclosure regimes exist and where to find them. Civil society watchdog organizations may be helpful in locating resources.

However, national asset disclosure databases may not be easy to find via the front end of a government website.

Searching “asset disclosures” on a government site doesn’t always lead to anything fruitful. But if you search Google for “[insert PEP name and country] assets disclosure,” helpful results can show up – even if it’s a story from a national paper referring to where the assets disclosure database of that country is found.

Even when “disclosure” laws have been passed, however, the submissions may not be made public. Shaking them loose may require filing a freedom-of-information request or even legal action.

In Sri Lanka, a local chapter of Transparency International (TI-SL) challenged secrecy provisions that allowed members of the public to see an MP’s asset declarations (for a fee), but made sharing that information illegal. Following new Right to Information (RTI) laws in 2017 and a prolonged appeals process, the Prime Minister was ordered to release his assets declaration and 10 MPs subsequently submitted their asset declarations to TI-SL for public disclosure.

Sanctions lists can also be a useful tool for establishing more details about the links between companies and individuals. The United States, for example, not only sanctions an entity but all companies majority-owned or controlled by them. Though assets are not usually disclosed on sanctions lists, being aware of often complex interlinked interests allows journalists to better understand where assets may be found.

There are many sources of such information, including OpenSanctions, the Publications Office of the European Union, the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, and War & Sanctions. The United Nations Security Council also publishes a list of individuals and other entities and groups subject to sanctions.

Journalists and Private Companies Create Databases

Journalists have sometimes enhanced official asset disclosure records, putting them online and adding information to them, sometimes with public input. This task has proved challenging, however, and some such efforts are now out of date.

In Serbia, KRIK, a journalism network and GIJN member that investigates crime and corruption, began publishing a database listing the properties of Serbian politicians in December of 2016, as described in an article published by GIJN. KRIK supplements the official information, for example, by using a real estate expert to value properties.

Reporters from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo (CIN) collected more than 2,100 documents about 120 politicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina. These include asset declarations, land records, incorporation documents for companies owned by politicians, indictments and rulings against them and other official documents.

In Argentina, citizens were invited to look at an online database that simplified the top 800 public officials’ asset declarations, though it too now seems out of date.

More recently, Tortoise Media and Sky News created the first fully searchable database of secondary employment, gifts, and other donations to British politicians, the so-called Westminster Accounts. Due to the nature of financial disclosures in the UK, gathering data on an MP prior to this often required trawling through numerous databases, meaning that the finances flowing to an individual were not always easily accessible for public scrutiny.

Tortoise Media and Sky News’ fully searchable database of secondary employment, gifts, and other donations to British politicians. Image: Screenshot, Tortoise Media

Private sources of information on PEPs also exist, but are primarily used by financial institutions. In many commercial contexts, research into finances is a crucial part of legally required due diligence. Private investigators have access to certain materials not available to journalists, such as credit reports and motor vehicle registrations.

But access to these proprietary databases is expensive.

Getting Creative to Fact-Check Disclosures and Find Assets

Examining the accuracy of asset disclosures is an obvious starting point for any investigation.

One first step is to look at disclosures that can be checked, like verifying the claimed value of real estate or of stock holdings. While doing this basic research, looking at the assets of family members, while controversial, may also be justified. Purchases made in someone else’s name are a classic way to disguise assets.

Real estate records can be particularly valuable as well. They may show sales prices and the official valuation of the property (see GIJN’s Guide on Property). Also look for documents about improvements made to a property, such as building permits. Public records of many kinds should be examined for additional information.

A significant challenge is the possibility of hidden assets abroad, such as real estate, and again public databases can be tapped. Another red flag is when the declared income and assets don’t match visible signs of a free-spending lifestyle. Using social media to track your subject’s travel, purchases, and even accessories like watches, may turn up leads, such as vacation pictures revealing previously unknown vehicles, properties, yachts, jets, artwork, watches, or even horses (see GIJN’s guides on tracking planes and tracking ships).

Searches of court cases, including divorce proceedings, may be another productive area to search for asset information. In addition, other government databases may be helpful, such as lists of persons obtaining agricultural subsidies.

Knowing where an official worked before being designated a PEP can provide context and leads. Find out if the individual owned or co-owned any businesses. This task can be especially difficult if there are incorporated companies or shell companies (see the GIJN Guide Researching Corporations and Their Owners).

Resources

OpenCorporates is a major database on corporate ownership.

OpenScreening, a collaboration between OpenSanctions, Linkurious, and Open Ownership, allows millions of open data records to be explored to help uncover hidden relationships between beneficial owners, politicians, sanction targets, and networks of companies.

The Offshore Leaks Database created by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) now includes more than 810,000 entries on offshore companies, foundations and trusts from the Pandora Papers, Paradise Papers, Bahamas Leaks, Panama Papers and Offshore Leaks investigations. A three-part series on ways to use the database covers searching by location, the networks and metadata in the database, and investigating companies. For example, how they revealed a former Czech prime minister was using offshore companies to buy property.

Aleph is the global, follow-the-money data archive built by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

Finally, basic shoe leather journalism often yields good results, including talking with friends, colleagues, and critics of a PEP.