Palestinians facing famine gather to receive meals from the nonprofit organization Rafah Charitable Kitchen, in Khan Yunis, in the southern Gaza Strip, on January 2025. Image: Shutterstock

Investigating War Crimes: Starvation

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: What Is Legal in War?

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Forced Displacement

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Starvation

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Environmental and Property Damage

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Banned and Restricted Weapons

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Arms Trade

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Combatants and Others Engaged in Hostilities

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence and Information

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Command Structures

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Tracing War Criminals

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Finding the Missing

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Documenting with Photo and Video

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Interviewing Victims and Survivors

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Physical and Digital Security

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Self-Care for Covering Traumatic Events

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Resources and Tipsheets

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

GIJN Launches First E-Book — Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Editor’s Note: This chapter is a new addition to the GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes, which was originally published in September 2023.

Food has been used as a weapon of war across cultures for millennia, from ancient sieges to modern blockades of humanitarian aid. In addition to conflict, factors such as the climate, the economy, or displacement may also contribute to food insecurity. In 2025, 343 million people faced acute hunger, with the majority, 65% percent of them, in fragile or conflict-hit countries. According to food security experts, in early 2025, Sudan and South Sudan, the Gaza Strip, and Haiti are facing the worst crises.

Even when wars ended, food shortages remained because of the disruption they created, forcing families to leave their homes, jobs, and sources of sustenance. Civilians are forced to extremes, ranging from selling all their personal belongings, begging, and skipping meals to eating tree leaves, soil, and cats when food security levels hit the bottom.

At the same time, conflict and hunger reinforce each other. Deliberately subjecting civilians to starvation methods is, therefore, quite difficult to prove in situations of armed conflict.

International Humanitarian Law (IHL) broadly defines starvation as acts that deprive a civilian population of objects indispensable to its survival, implying not just an outcome (civilians starving) but also a cause. While starvation was first explicitly prohibited as a method of warfare in 1977, it took another 20 years for the International Criminal Court Statute to include it as a war crime in international armed conflicts. To this day, the Court has never applied this war crime, making it even more imperative for journalists to investigate the issue.

The Legal Approach

International Humanitarian Law and experts on relief have used the term Objects Indispensable to the Survival of Civilians or OIS to sum up a non-exhaustive catalogue of means and objects required to keep a population alive. By deliberately depriving civilians of OIS, ruling authorities or governments use starvation of civilians towards an advantage. Such deprivation may take on many forms, including intentional destruction of livelihood, crops, and markets; seizing or destroying food stocks; blocking humanitarian aid, and/or forcing masses into displacement, which means entire communities have lost their homes and, therefore, sources of income and livelihood. Famine also results from a lack of clean water, sanitation, and from health care, which is a massive challenge in conflict situations.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court states: “Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare by depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival, including willfully impeding relief supplies as provided for under the Geneva Conventions,” constitutes a war crime in international armed conflicts. In 2019, the ICC statute was amended to include starvation of civilians as a method of warfare in non-international armed conflicts. However, to date, this amendment was only ratified by 20 out of 124 member states.

It’s important to note here that international humanitarian law doesn’t criminalize the use of starvation as a method of war against combatants. This complicates the legal accountability of individuals when civilians starve alongside fighters. On urban battlefields, it may also present a challenge to prove whether deliberately starving civilians was an operation’s intended purpose. Therefore, collecting evidence to prove intent becomes a crucial issue for journalists investigating starvation as a weapon of war. More often than not, the ‘fog of war’ will add a layer of uncertainty over the reasons behind the starvation of civilians that those causing it will want to hide behind. That is why tracking the impact of war on a civilian population closely and investigating the background to famine is particularly crucial in times of armed conflict.

Starvation and Famine in Conflict Today

Case of Sudan

In the past decade, there were four instances where famine was recognized globally. Sudan and South Sudan accounted for three of the four crises. Before its independence in 2011, South Sudan was part of the larger Sudan, which for decades also has suffered from long-running civil wars, coupled with famines that claimed the lives of thousands, and where central governments played a major role in starving its people.

In 2025, when this chapter is being written, parts of Sudan and South Sudan are still grappling with simultaneous famines and severe hunger crises.

Health workers carry Naimat Ahmed, 10, who is dying, into an isolation ward at a health clinic run by the medical charity Doctors Without Borders in Adre, eastern Chad, August 5, 2024. Ahmed’s family fled the war in Sudan after waves of attacks on her Masalit community in Darfur, including one where her grandmother was shot and killed and her older sister was wounded. With her mother and nine siblings, she spent her last year living in a refugee camp. Famine was declared in North Darfur in August 2024, and aid agencies warned that nearly 222,000 Sudanese children could starve to death. Image: Finbarr O’Reilly, VII Foundation

During the civil war that broke out in April 2023, Sudan suffered from numerous acts depriving millions of Sudanese people from objects indispensable to survival. The paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which is at war with the Sudanese Armed Forces, raided, assaulted, killed, and looted entire cities and villages across the country, forcing millions to flee. The Sudanese military relied heavily on air power, destroying markets and killing civilians in an attempt to prevent the RSF from expanding its foothold and force the militia out of areas it had seized.

When aid agencies fled Sudan’s war-torn capital, Khartoum, and repositioned themselves in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan, they tried to provide humanitarian relief. Instead, they were faced with increasing restrictions preventing them from reaching people and distributing badly needed aid. With nearly 12.4 million people displaced from their homes, the amount of aid available covered only a fraction of the need and even that was hard to deliver.

In addition, the government has denied the existence of famine, and recently suspended participation in the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a common global scale for classifying the severity and magnitude of food insecurity and malnutrition.

The Gaza Strip

Israel’s land, air, and sea campaign in Gaza, triggered by Hamas Oct. 7, 2023 attacks, represents the most striking examples of starvation as a weapon of war and the destruction of all necessities such as food, water, and fuel. This has included razing agricultural areas, dispossessing people from their personal assets, and forcing hundreds of thousands into displacement many times, all while 70% of Gaza’s population suffers from no access to clean water. The blockage of fuel by Israel incapacitated bakeries, hospitals, sewage pumping stations, water desalination plants, and wells.

At a May 2025 protest in London, demonstrators express outrage over the lack of food for Palestinians in Gaza. Image: Shutterstock

In December 2023, the UN World Food Programme (WFP) reported that nine out of 10 households in northern Gaza and two out of three households in southern Gaza had spent at least one full day and night without food. The situation has worsened since: May 2025 data simulations from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) point to “the average Gazan eating just 1,400 calories per day — “or 67 percent of what a human body needs to survive” (2,300 calories) as of May.”

Although Israel hasn’t ratified Additional Protocols I & II to the Geneva Conventions, the prohibition (against starving civilians) is recognized as reflective of customary international humanitarian law in both international and non-international armed conflicts. Parties to a conflict may not “provoke [starvation of a civilian population] deliberately, particularly by depriving it of its sources of food or of supplies.”

In November 2024, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, over “the war crime of starvation of civilians as a method of warfare; and the crimes against humanity of murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts.”

Tools for Journalists Investigating Starvation

Charting an Investigation

Detailing the hunger toll from wars is one of many ways to tell a story about how starvation is used as a weapon. However, gathering data from the field in countries at war in order to determine the severity of hunger is challenging because of access restrictions, which ultimately make it hard for food security experts and the so-called Famine Review Committee to reach an official decision.

Food insecurity and mortality (from hunger or hunger-related diseases) are two of the most important parameters. However, those are very hard to assess when there are also ongoing wars and conflicts. Amid airstrikes and bombings, it might be hard to distinguish deaths related to trauma from deaths caused by hunger. Severe Acute Malnutrition or SAM levels, measured by different methods for children under five, are the third important measurement. However, that too is difficult because nutrition workers are required to be physically present at health facilities to take a child’s measurements.

Global Data Mining

Journalists investigating famine can start by mapping hunger hotspots around the globe, based on WFP tools like this one and this one, and Global Hunger Index. In some incidents, countries are forced into the top hunger hotspots when governments and ruling authorities manipulate data and international agencies don’t question the analysis. In Yemen, Houthi rebels in control of the northern part of the country tried to push food security experts to classify areas under their control as facing severe hunger or worse to get more international assistance. After a pushback from experts, a data analysis from Houthi-controlled areas in Yemen was not published for fear of reprisals, leaving the hunger situation in these areas unclear.

In other incidents, spiking malnutrition rates might not be related to food insecurity but to a disease outbreak that causes malnutrition and is mistakenly portrayed as hunger.

The list may, however, point the journalist in a direction where conflicts have ensued. Pre-existing hunger in a country in conflict has a high possibility of being weaponized. Interviews with local food security experts should give journalists a fair understanding of the conflict dynamics and how providing a necessary diet is unfolding in such countries.

Amidst an ongoing civil war, children in the Houthi-controlled Yemeni city of Taiz carry bags of food, in 2022. Image: Shutterstock

Sources to Interview

To investigate the warring parties’ roles in starving people, humanitarian actors can be a strong starting point and provide a wealth of information for journalists. They can provide insights about an unfolding humanitarian crisis, hunger levels, coping mechanisms, levels of malnutrition, along with the root causes of the ongoing crisis. They can also share stories they hear from the local community about the parties in the conflict and what warfare tactics they are using, including starvation.

However, to prove intent of warring parties’ use of starvation of civilians as a weapon of war, journalists need to collect as much testimony from the field as possible from health workers, activists, community leaders, and those waiting at the end of the aid supply chain for life support. They can help document deprivation of badly needed nourishment by gathering video, audio, and hard evidence that show the chronology of the events. Journalists should talk with former soldiers or fighters to question them about whether they were given orders to starve people. Journalists should also look online for open source videos or audio or written statements in areas where leaders and commanders are looting and killing or giving orders to starve people, or prevent humanitarian aid delivery.

Tools To Investigate Starvation and Famine

Journalists find it hard to assess whether a certain area or region is suffering from extreme food shortages or outright famine given the complex data needed to estimate mortality, malnutrition, and food security in a certain region.

Using The IPC’s Famine Measurements

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is a common global scale for classifying the severity and magnitude of food insecurity and malnutrition. Experts detect famine using a set of food security, nutrition, and mortality databases – a mortality rate of at least two deaths for every 10,000 people, 20% of households face extreme food shortages, and 30% of the children under five suffer acute malnutrition. These are the IPC’s signs of a famine.

The IPC plays a critical role in identifying famine conditions and informing the response needed to save millions of lives. It’s now the primary mechanism the international community uses to analyze data and conclude on whether famine is happening or is projected to occur in a country.

The IPC’s five-phase classification system covers more than 30 countries and classifies food insecurity on a scale of one to five, where IPC 5 is either catastrophe or famine. The IPC doesn’t collect data to determine food insecurity; however, it relies on many databases gathered by international and local agencies operating in each of the countries the IPC covers.

When thresholds of malnutrition, mortality, and food consumption are crossed by a certain percentage, areas and nations are classified as having famine, prompting a Famine Review Committee, run by a group of international experts, to confirm and assess the validity of the analysis.

Once a nation or a particular place is classified as IPC 3 or worse, action is needed. International donors and relief agencies are the typical first responders. However, with increasing hunger crises sweeping the world, response often comes after a famine is found, meaning people have already begun dying of hunger.

Even then, politics, fatigue, mismanagement, and corruption get in the way of making swift responses to the most needy crises, such as the situation in Gaza and Sudan where famine was found.

A Palestinian child in Gaza holding food dispensed by an aid agency. Image: Shutterstock

Other Resources

The IPC offers this series of self-paced courses, where journalists can understand the concepts on which the IPC is based, and which provides all the necessary information to appreciate and critically use IPC products.

IPC-CH Dashboard: A visual display of the total number of people experiencing or facing high levels of acute food insecurity, classified in crisis or worse.

Food Security Cluster (FSC): Co-led by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP), the FSC has been coordinating food security responses during and after humanitarian crises since 2011. The FSC coordinates a network of partners — including UN agencies, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) — across 29 countries to address emergency food needs and improve livelihoods promptly.

Food Security and Livelihoods | Humanitarian Action: A database published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). It provides live data on the needs of people-in-crisis situations across the world and the response to these needs. It also provides an overview of financial aid delivered to a particular situation or region.

Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC): Led by UNICEF, the GNC responds to nutritional crises arising in various regions, where the scale of the crises is so large that a single organization or UN agency cannot effectively respond to it. They have databases to show how they have responded to nutritional crises in various countries, in addition to various toolkits to prepare for such crises.

Standardized Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions (SMART) Survey for Nutrition, Food Security and WASH: SMART Surveys are conducted in many countries across the world to assess the nutritional status of populations. Journalists have to search under each country’s nutrition cluster to find smart surveys like this one from India:

Logistics Cluster: A look at the minutes of the logistics cluster of international humanitarian operations gives a glimpse into the restrictions that aid faces to reach people in need.

ReliefWeb: Run under the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the website provides information on humanitarian crises and disasters across the globe – highlighting both response and need.

Financial Tracking Service (FTS): The FTS is another database under the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Response (OCHA). It gives real-time information on humanitarian findings and needs throughout the world.

Humanitarian Action: Also run under OCHA, it’s a resource for understanding and responding to global humanitarian crises, providing information about ongoing emergencies and the humanitarian response efforts.

Finding TPMs: The UN, donors, and INGOs also rely on so-called third-party monitoring companies (TPMs), which are providing oversight reports about aid. To find companies providing services to UN agencies, journalists can search the UN procurement division. Each country also has its platforms for suppliers, and in the case of Sudan, “Sudanbid” is where journalists can get information about which agency is actively operating on which specific project in which areas. Journalists should identify staffers at any TPMs and suppliers of services to the UN and INGOs, and cultivate sources that can give insights about the integrity of the relief operation using social media platforms like LinkedIn.

Satellite Imagery: In the cases of Sudan and Gaza, satellite imagery was an important tool to uncover famine-related stories. Reuters and Human Rights Watch (HRW) used satellite images to examine different issues related to famine. In one of these stories, focused on OIS (Objects Indispensable for Survival), HRW showed how the Israeli assault razed farmlands in the Gaza Strip. Reuters used satellite images to show the accelerating rate of graveyards and cemeteries in Darfur to give rare evidence of increasing mortality in hunger-stricken regions. For more on satellite imagery, read the related GIJN guide.

Case Studies

Reuters’ Sudan Series

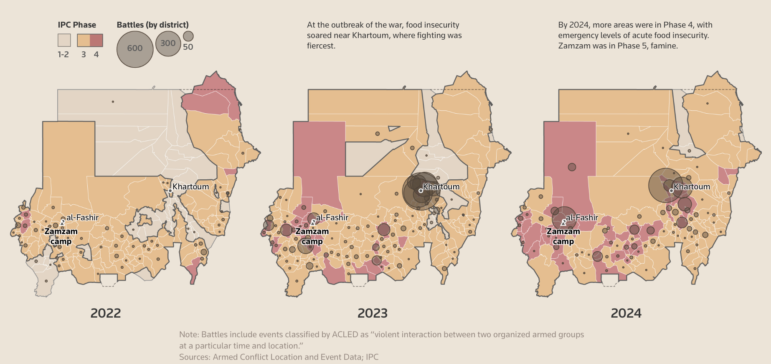

Reuters published a series of investigations showing for the first time that the famine had expanded from one area in Sudan to five areas by the end of 2024. Their reporting also predicted the famine would expand to five more areas outside Darfur by May 2025. Using graphics, the Reuters team illustrated what it means to have a population in famine while exposing how the Sudanese government has tried to bury the only evidence, the spiking mortality in Darfur as a proof of famine.

The data team counted the dead using hundreds of satellite images over several years and interviews with dozens of community leaders in Darfur to show the swelling cemeteries from the sky. The team focused on areas that weren’t touched by violence, so the deaths are mostly related to hunger and disease.

“In all, Reuters identified 14 burial grounds in five communities across Darfur that have expanded rapidly in recent months. The area of new graves at these burial grounds has grown three times faster in the first half of 2024 than in the second half of last year,” the report explained.

One expert described the cemeteries as “canaries in the coal mine” of famine.

As part of the series, Reuters found that the central government blocked access to aid in parts of the country, including the most isolated areas of the Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan. The United Nations relief agencies like WFP and WHO were crippled and unable to reach millions in need simply because the UN can’t violate governments’ sovereignty. The United Nations agencies must obtain permission from the internationally recognized government of Sudan, which the world body recognizes as the party enjoying sovereignty.

The government has told aid organizations “there are no legitimate needs in Darfur, so you should not work there, and if you continue to respond to needs there, you should not expect visas,” said one senior aid official, who asked not to be named. The government didn’t respond to Reuters’ questions for this series.

Reuters used satellite imagery and dozens of interviews to map the spread of food insecurity in Sudan over two years using the IPC’s famine classification system. Image: Screenshot, Reuters

A large group of Reuters reporters and data journalists also published an explanatory and investigative piece of journalism in a rare attempt to take a closer look at the systemic failure of the global famine early warning system, especially in the context of conflicts and civil wars.

It tried to address the dilemma found in Sudan — that early warning requires contribution and buyout from central governments or major parties. But these governments are at times at war with others groups within their borders, which poses a conflict of interest and undercuts the entire system’s ability to detect and warn of famine when used as a tool of war.

What is also unique about this story is that it laid bare the many weaknesses in the global system and the lack of rapid response to famines and severe hunger crises engulfing the world.

The story looked into other weaknesses and barriers, including the fact that the early warning system requires massive amounts of qualitative and quantitative data, which become impossible in a war context. It also showed that governments, parties of conflict, can also hold sway over data by exaggerating a hunger crisis or undermining it.

Their reporting relied on large databases extracted from different sources, including the Food and Livelihood Clusters, which represent humanitarian partners coordinating to food security responses, meeting minutes from humanitarians focusing on logistics, and leaked correspondence. The reporters also underwent some training by the IPC to understand how they are supposed to work to be able to tell what went wrong.

Dying for a Bag of Flour

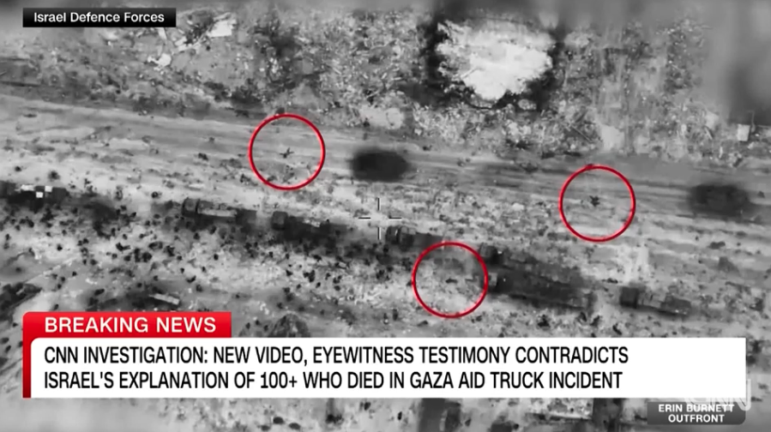

In this investigation into the “flour massacre,” CNN gathered social media videos and footage to challenge Israel’s narrative about a deadly aid delivery in Gaza on February 29, 2024. The incident, one of the deadliest since Gaza came under attack by Israel following the Oct. 7 Hamas assault, left over 100 dead and 700 injured after the Israeli army opened fire at people rushing to receive aid.

Rear Adm. Daniel Hagari, the Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) spokesman, said: “Soon after that soldiers had not fired directly on Palestinians seeking aid, but rather fired ‘warning shots’ in the air.” However, CNN analyzed dozens of videos and collected testimonies that cast doubt on the military’s official version of events.

The incident comes amid a pattern of attacking hungry civilians in Gaza. The UN noted that over 14 recorded incidents of “shooting, shelling, and targeting groups gathered to receive urgently needed supplies from trucks or airdrops” occurred between mid-January and the end of February 2024.

Using social media videos and user generated footage, CNN’s investigation contradicts the Israeli army’s official account of the so-called flour massacre, where more than 100 Palestinians were killed and 700-plus were injured. Image: Screenshot, CNN

Starving Gaza

Two investigations found the Biden administration played a key role in providing cover for Israel to continue starving Gaza.

The Independent investigated the Biden Administration’s “missteps, missed opportunities, and political choices” in the Gaza starvation campaign, calling it “an entirely preventable catastrophe.” The exposé was based on interviews with former and current US officials and aid workers in Gaza, along with internal documents, including 19 memos by USAID staffers. The interviews and the documents showed that the US provided “diplomatic cover” for Israel to create the conditions for famine.

In response, the Biden administration highlighted to The Independent “Mr. Biden’s repeated requests for the Israeli government to open up more crossings to aid, and pointed to temporary increases in aid trucks entering Gaza as proof of what they describe as his effectiveness.”

The second story on the same incident, by ProPublica investigated how two US government bodies concluded Israel was blocking aid to Gaza, but the State Department ignored them. The findings by USAID and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration both reported their findings about Israel’s role in starving Gaza to then Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, which would have required that the US administration halt weapons deliveries, including US$830 million allocated for weapon sales to Israel.

A State Department spokesperson told ProPublica that “the US had deep concerns during the period since October 7 about action and inaction by Israel that contributed to a lack of sustained delivery of needed humanitarian assistance.'” The spokesperson added that Israel subsequently took steps to facilitate increased humanitarian access and aid flow into Gaza.

Editor’s Note: While this chapter primarily addresses the starvation of the general civilian population, recent patterns in armed conflicts also indicate that a troubling number of conflict parties have also employed starvation as a means of mistreatment against detainees. Multiple reports from conflict settings document the deliberate use of deprivation of food and other items necessary for survival. Such conduct is highly relevant to international criminal accountability, too, as it may amount to crimes against humanity, torture, or war crimes under international law.

GIJN’s Resource Center Director, Nikolia Apostolou, contributed additional resources to this guide. Legal review by the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice.

Maggie Michael is an investigative journalist at Reuters who previously reported for ICIJ out of Cairo, Egypt, from 2021 until February, 2023. She has more than 15 years of experience covering conflicts across the Middle East, and has gained deep knowledge of its political, social, and cultural dynamics. In 2019, she was part of an Associated Press team that won many international awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting, Michael Kelly Award, IRE, and McGill Medal for Courage for groundbreaking investigations of corruption, torture, and other war crimes in Yemen, a country plagued by protracted civil war.

Maggie Michael is an investigative journalist at Reuters who previously reported for ICIJ out of Cairo, Egypt, from 2021 until February, 2023. She has more than 15 years of experience covering conflicts across the Middle East, and has gained deep knowledge of its political, social, and cultural dynamics. In 2019, she was part of an Associated Press team that won many international awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting, Michael Kelly Award, IRE, and McGill Medal for Courage for groundbreaking investigations of corruption, torture, and other war crimes in Yemen, a country plagued by protracted civil war.