How They Did It: Investigating the Trafficking of Girls from Nepal to the Gulf

Trafficking Teenagers: Pramod Acharya’s investigation exposed a human trafficking ring which moved under-aged girls from Nepal to the Gulf region. Photo: Centre for Investigative Journalism, Nepal

Sindhupalchok is only 50 miles north of Kathmandu but it’s not easy to get there. You have to travel through remote villages and over difficult terrain to reach the area. The craggy hills and lack of infrastructure means vehicles have limited access, leaving its denizens to walk an entire day to reach even the closest local market.

I have been regularly visiting Sindhupalchok since 2015, when I first reported on a devastating earthquake in the region, which left nearly 9,000 people dead. But during a visit last year I stumbled across a story of how girls from the district were being trafficked to Arab nations along the Persian Gulf, recruited to work as housemaids. What I ended up unraveling took me across the country to track the disturbing rise in the trafficking of under-age girls.

Rumors

I first heard the rumors just a week after the earthquake. Residents in the area were telling me how traffickers would convince the families of under-age girls to send them to Gulf countries where they could “earn them a lot of money.” While I was aware of the more common form of human trafficking from Nepal – the selling of girls and women into the sex trade in India – this trend was new to me. Traffickers were helping girls fake their birth dates and assisting them with obtaining passports, which would make it easier for them to be trafficked under the veil of foreign employment. Although the passports were being issued from Nepal and used the girls’ real names, their faked birth dates meant they qualified to go abroad for foreign employment.

I knew I was facing a complex investigation. In order to figure out how the traffickers were operating in the region, I would have to show how they were assisting with false documentation, how they were convincing the families, how they were crossing the Indo-Nepal border, and how they were successfully sending girls from airports in India to the Gulf.

TIP: DOING YOUR RESEARCH

While I had covered stories about human trafficking before, so I knew the basic legal framework, it was only after my investigation that I spent time looking into the legal aspects of foreign employment and human trafficking, as well as the evolution of trafficking in Nepal in detail. It’s a better idea to do more preparation before heading out, so you can understand the legal aspects surrounding trafficking in the specific region. But while that initial background is important, once you have conducted your investigation, you are likely to find legal loopholes which also need to be addressed.

Going Undercover

Image: Wikimedia Commons

I began my investigation at the district administration office in Chautara, which issues citizenship and passport documentation.

The first week I just observed, watching as young girls came to the office for their papers and passports, without revealing my identity. I tried to read their body language and figure out the socio-economic background of their parents, who often accompanied them. I casually asked them about their age and education and, during our conversations, they would tell me they about their plans to immigrate overseas for employment. Many of these girls were between 14 and 15 years old, came from humble backgrounds and were barely literate. Some told me their relatives or neighbors supported their overseas employment plans. That week I counted at least 15 girls who were applying for passports with fake birth dates. Something was obviously terribly wrong.

At the end of the week, I revealed my identity as a reporter, asking one of the officers if he often just moved ahead with documentation even if he knew these were fake dates. The official admitted that he had to provide documentation to the girls even if he knew the birth dates were inaccurate; their parents often insisted, arguing that they were the only people who knew the actual age of their children.

TIP: CONSIDERING GOING UNDERCOVER

It was clear to me that I had no choice but to begin my research on this story undercover. I knew I’d be received with extreme reluctance, if not outright denial, by the families were I to reveal my identity before understanding more about how the operation worked. I might also be putting the girls and their families at risk if they knowingly spoke to a journalist. Often girls would arrive at the office with their traffickers, who would stay stationed close by while the girls completed the documentation process alongside government officials who were at least negligent and, and sometimes complicit, in issuing the fake documents.

Journalists need to figure out for themselves whether going undercover — which should be a last resort — is necessary in their individual situation, taking into consideration both the importance and sensitivity of these stories and considering the possible ways of investigating them.

On the Front Lines

I knew I needed to talk to girls who had been trafficked who would be willing to speak to me on the record, so I travelled to the district of Kanchanpur at the Indo-Nepal border, known as one of the gateways of human trafficking.

Once I arrived at the border, I met with police officers and people from Maiti Nepal, an NGO which fights human trafficking. The border police and the NGO were able to provide recent data related to human trafficking from that route, while police also allowed me to meet with some traffickers who were in custody.

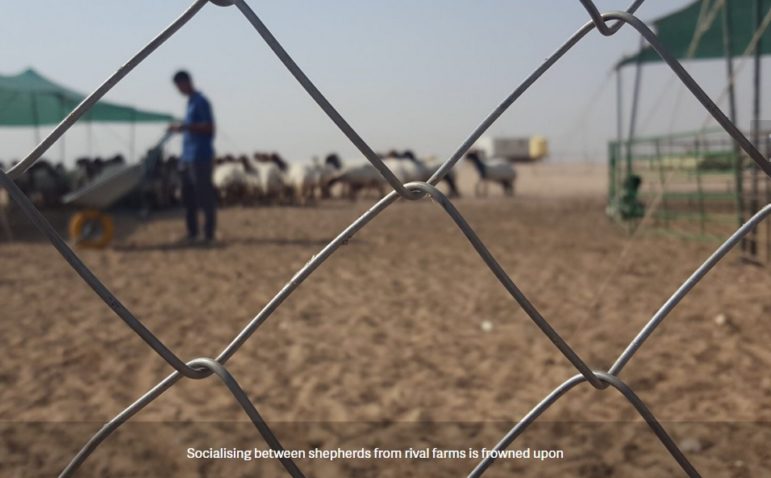

While meeting with the Nepali police, I was told that the Indian police had just detained six girls who were being trafficked from Nepal. But when I tried to contact them, they gave a curt reply, only telling me they handed the girls over to Maiti Nepal. I rushed to the NGO’s office and met the girls, all of whom had been promised caregiving jobs in Kuwait. They were between 14 and 15 years old, but their new passports listed their ages as between 21 and 22; even more troubling was that some of the traffickers were their neighbors or relatives.

Evidence was piling up, but I still didn’t have enough for a story. I needed to find out where the traffickers lived, how long they had been involved and how large their network was. I approached Indian police for answers, but they simply evaded my questions.

TIP: WORKING WITH OFFICIALS AND NGOS

In the end, it was Maheshwari Bhatta at Maiti Nepal who helped with additional information about the traffickers involved with the six girls. Eventually, Indian police also agreed to brief me about the people who were involved in that trafficking ring, and they confirmed the process of faking birth dates on the documents which enabled these girls to travel to Kuwait, Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

NGOs can be an excellent source for journalists working on human trafficking stories. Because they are working daily on the ground, they can assist in sensitive situations where access might be difficult if you were to go on your own. They can also provide relevant background and statistics. Of course, you cannot completely rely on the information provided by NGOs as there always remains a possibility of manipulation, exaggeration and bias, so information provided needs to be verified.

Collaborating

While I had the basics of my story down, I still needed to talk with a girl who had been trafficked. I returned to Sindhupalchok. This time, I asked for help with a local journalist, Kishor Budathoki. He was able to help me find my way around the area and to better understand the local culture.

We were able to meet with a couple of returnees, but they declined to speak in detail because they had been trafficked by their own relatives. Budathoki was able to arrange a meeting with some local police officers, with whom he had personal relationships. The police ended up giving us the statement of a young girl who had been trafficked to Dubai. She was barely eight years old when she was sent by her aunt to India, where she was sexually exploited for seven years, after which she was sent to Dubai to work as a domestic worker.

On the Trail of Traffickers: Girls rescued by Uttarakhand Indian Police and the NGO Maiti Nepal, Kanchanpur; and a statement from police from the investigation. Photo: Maiti Nepal.

TIP: WORKING WITH OTHER JOURNALISTS

It’s always far easier for journalists to work in countries with which they are familiar. But when reporting on cross-border issues such human trafficking, this becomes even more relevant. An investigative journalist from India with access to authorities there – including police and airport officials – would have been a tremendous help. They could have also assisted with gathering details of traffickers who reside and handle their business in the country. Collaborating with a journalist from Gulf could have made the story more useful by incorporating the experiences of the trafficked girls already in that region. It would have also helped from an official standpoint as extremely limited information is available over the phone or email with officials at Nepali embassies based in the Gulf states.

Personal Security

While I was in the remote village of Selang in Sindhupalchok district, a journalist friend was alerted by his personal acquaintances that some ruffians, after finding out that we were reporting on human trafficking, were coming after us. We knew police presence in the area was limited so we notified the district police about our possible risks and left the area. We ended up staying secretly in a teacher’s house in the village, returning using different route.

TIP: REALIZING THE RISKS

When working on a story about human trafficking in remote villages, it was important to keep the investigation — the angle, seriousness and the scale of the story — a secret because a family member, government official and even police officers can be part of a complex scheme like this. If a story is threatening to those complicit, you can be at risk of a physical attack. So, before starting actual reporting, prepare the list of people you are planning to meet during the investigation and assess any possible security threats.

Talking With the Victims

While it was important to get the stories of victims, I struggled to have one talk on the record, which can often be the case in these types of sensitive situations involving young girls. Other journalists are likely to face the same issue; understandably, victims aren’t always prepared to talk about their experiences as they fear the traffickers may harm them and their families, both physically and psychologically, if they unveil the truth to anybody. In Nepal, where the victims’ own families are involved in the trafficking chain, it is even more difficult. If you find yourself in a situation where you are unable to talk to a victim face-to-face, you might try what I did: use a victim’s police statement. You can also try approaching anti-human trafficking organizations who rescue victims en route to an overseas destination.

**** For more on Human Trafficking resources, see GIJN’s Resource Center for Human Trafficking, Forced Labor and Slavery and Human Trafficking (Gulf Region).

**** For a look at the author’s investigation into trafficking minors from Nepal to the Gulf, see his November 10, 2017 story, Pipeline to peril: Desperate for work, how underage girls from Sindhupalchok are lured into trafficking in Gulf countries.

Pramod Acharya is a leading investigative journalist from Nepal and an assistant editor at the Centre for Investigative Journalism in Kathmandu. Over the years, he has produced several groundbreaking investigations on human trafficking, public health and malpractice in academia. He is currently a Dart Center fellow at Columbia University, New York.

Pramod Acharya is a leading investigative journalist from Nepal and an assistant editor at the Centre for Investigative Journalism in Kathmandu. Over the years, he has produced several groundbreaking investigations on human trafficking, public health and malpractice in academia. He is currently a Dart Center fellow at Columbia University, New York.