YanukovychLeaks Update: “The Project Is Becoming Bigger”

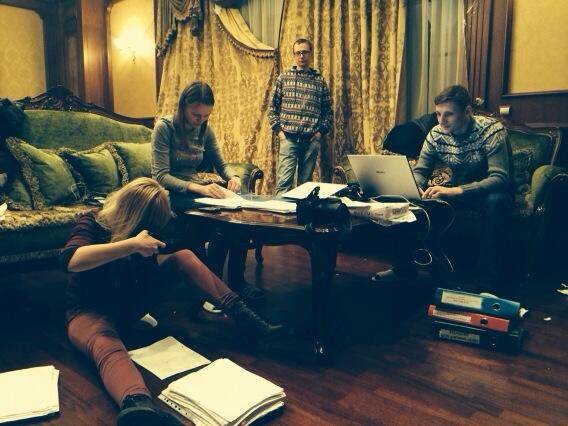

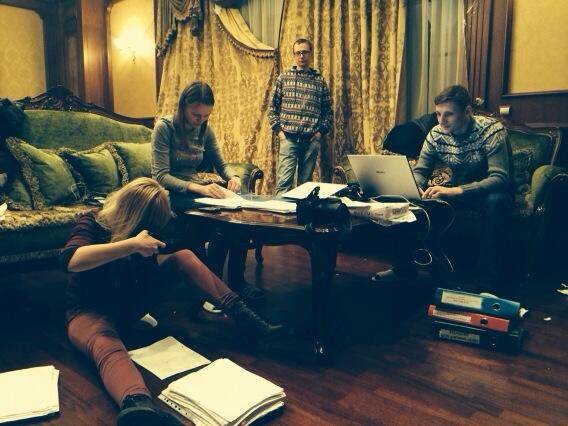

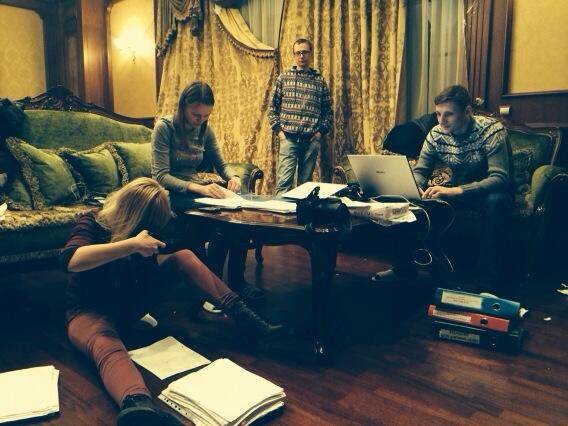

Ukraine’s newest investigative journalism center — in the Yanukovych mansion –preserving thousands of documents. Credit: Katya Gorchnskaya, Kyiv Post

The extraordinary story of how Ukrainian investigative reporters saved thousands of documents left by fleeing ex-president Viktor Yanokuvych has gone viral.

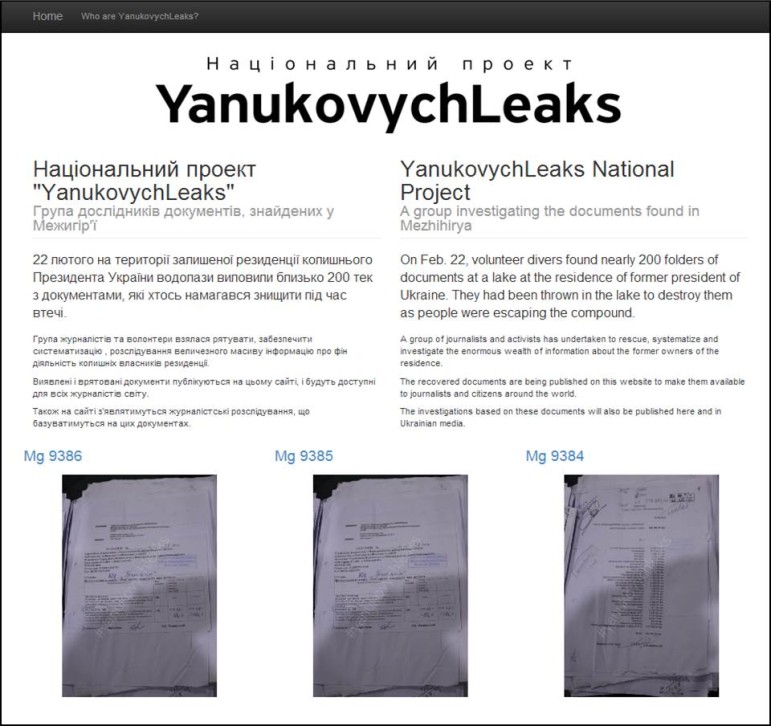

YanukovychLeaks.org, the site thrown together by an impromptu team of journalists and hackers, has received more than 600,000 visitors since going live on Tuesday – and those documents have been viewed 3.8 million times. “That means people really do care about transparency. It is valued,” says Drew Sullivan of the nonprofit Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which is helping provide resources for the project.

The project began last weekend after volunteer divers recovered 157 folders of 100 to 500 pages each dumped into a reservoir next to Yanukovych’s luxurious estate in Mezhyhirya, a historic district outside Kiev. The reporters then searched the compound and properties associated with it and have found as much as ten times that amount – more than 100,000 documents pages in all.

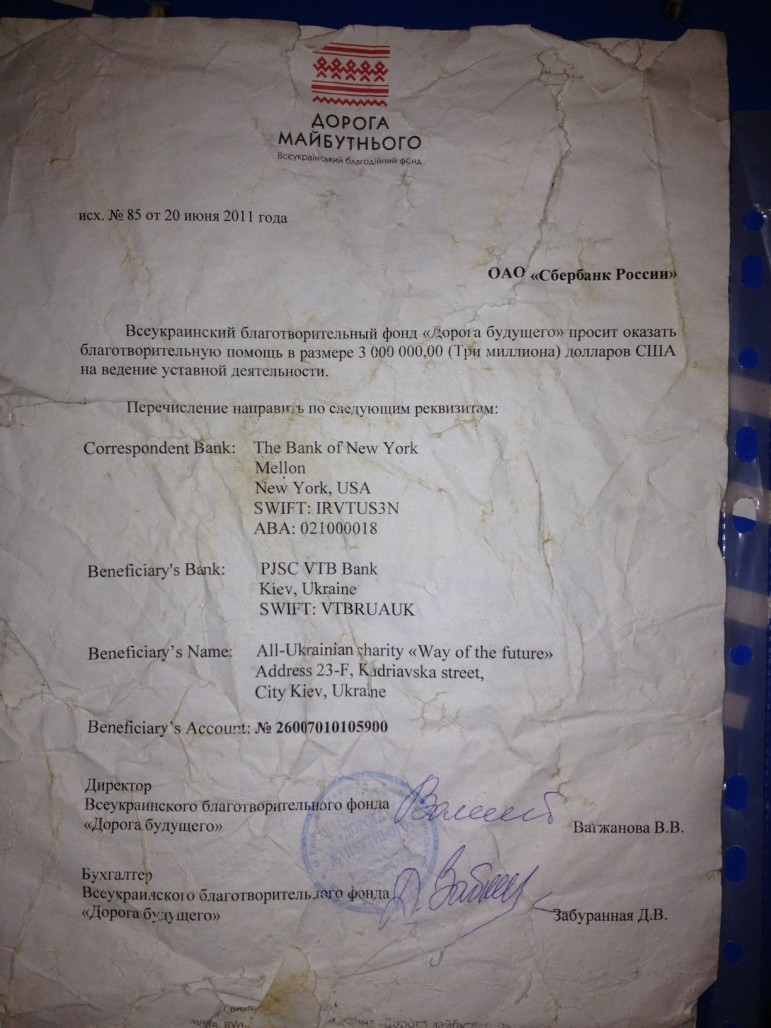

A look inside: This letter from a Yanukovych family charity to Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank, with major holdings in Ukraine, asks that $3 million be donated and transfered via the Bank of New York.

The YanukovychLeaks team, now numbering about a dozen journalists from a half-dozen outlets, plus volunteers, has worked around the clock to successfully dry and preserve the documents, even making use of a sauna at a nearby Yanukovich guest house. The team is now uploading them with some 20 scanners spread around the mansion. By midday Wednesday, the group had uploaded nearly 2,000 documents to the site.

“The project is becoming bigger,” says Natalie Sedletska, a member of the team. “OCCRP support is extremely helpful as their talented developers built a website within hours so we could start uploading very fast. Another amazing thing is the regular people who brought us driers and scanners, and are ready to help save these docs day and night.” (For Sedletska’s inside look at the YanukovychLeaks project, see her companion story, “The Walls Have Fallen.”)

There is urgency to the team’s task. On Wednesday, prosecutors presented a court order to turn over all documents but were surprised by the sheer volume of paper. They’ve agreed to take them from the group in batches after the scanning has been completed, but no one knows how long that agreement will last. The documents may implicate Yanukovych in bribery, abuse of power, and other criminal acts, and the acting government has issued an arrest warrant for the ex-president for the “mass killings” of civilians. More than 100 protesters were killed by riot police during the unrest in recent weeks.

Meanwhile, the story of how a disparate group of journalists rescued the documents is getting global attention. GIJN asked Oleg Khomenok, who is helping coordinate YanukovychLeaks, about why the project came together as it did. A veteran journalist, Khomenok has trained hundreds of Ukrainian reporters in his workshops for media NGOs Scoop and Internews. “This was a great opportunity that came at the right time to the right people who were trained and ready to react in a capable way,” he says. Many are young journalists who participated in Khomenok’s workshops over the years, and have been exposed to international standards of investigative reporting.

Meanwhile, the story of how a disparate group of journalists rescued the documents is getting global attention. GIJN asked Oleg Khomenok, who is helping coordinate YanukovychLeaks, about why the project came together as it did. A veteran journalist, Khomenok has trained hundreds of Ukrainian reporters in his workshops for media NGOs Scoop and Internews. “This was a great opportunity that came at the right time to the right people who were trained and ready to react in a capable way,” he says. Many are young journalists who participated in Khomenok’s workshops over the years, and have been exposed to international standards of investigative reporting.

Khomenok also credits the Global Investigative Journalism Conference, which was held in Kiev in 2011, with helping arm the reporters with the right tools and training. That conference attracted 500 muckraking journalists from 75 countries to the country’s capital. Last October, the Ukrainians also sent a large contingent to the subsequent global conference, GIJC13, in Rio de Janeiro. “Within three hours of the documents being found, five reporters who participated in GIJC13 in Rio met on the banks of the Dnieper in Mezhygirya to make real what they might not even dream about,” says Khomenok. “Now we have thousands of pieces of real evidence that may point to corruption, money laundering and other crimes.”

Others agree, pointing to the hard work done by Ukrainian journalists and international media groups in making a phenomenon like YanukovychLeaks possible. Since the fall of Communism, Ukraine’s independent media have been helped by nonprofits like the country’s Regional Press Development Institute, Denmark’s Scoop, and OCCRP, supported by grants from such outside donors as the Danish Foreign Ministry, USAID, and the International Renaissance Foundation, the Ukraine branch of the Open Society Foundations.

Bruce Shapiro, director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, has worked with Ukraine’s independent media since 2005. He notes that Ukraine’s investigative journalists have been on the front lines for years:

“The fact that a skilled corps of Ukrainian investigative journalists was ready, on a moment’s notice, to salvage, organize, and publish the Mezhihirya documents is itself an important part of the story. Less than a decade ago, Ukraine had little history of accountability journalism, and those reporters who asked hard questions faced persecution or assassination. Now Ukrainian investigative journalism is a force to be reckoned with”.

Why was that possible? “That’s because of a steady stream of trainings and workshops led by and for Ukrainian journalists, backed up by journalists and NGOs from other countries who have provided expertise, financial support, and publishing collaborations; it’s because of Ukraine’s first investigative journalism handbook, published in 2008; it’s because in 2011 the Global Investigative Journalism Conference brought hundreds of colleagues from around the world to Kiev, in a show of support for then-embattled Ukrainian news professionals,” says Shapiro.

The rapid rise of investigative journalism in Ukraine, Shapiro adds, made a real contribution to this year’s revolt against pervasive corruption and the demand for a culture of accountability. “Without Ukraine’s investigative reporters, Yanukovych might still be in power, and those documents would never, ever see the light of day.”

It’s often not easy to see the result of investments in independent media around the world, especially with press freedom suffering in places like China, Egypt, and Turkey. But here’s a case where relatively limited support has paid off. “What they have done is audacious,” says Drew Sullivan of OCCRP, a consortium of investigative centers funded by international donors. “These reporters come from the small independent media and nonprofits that have been at the cutting edge of reporting in Ukraine in recent years. They are used to sharing and cooperating in Ukraine and with their peers around the world. When you have good people like that, you just stand back and say: ‘How can we help?'”

David E. Kaplan is executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, which co-sponsors the biennial Global Investigative Journalism Conference. He is former director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a senior editor at the Center for Investigative Reporting, and chief investigative correspondent for U.S. News & World Report.