South Africans protest corruption by President Jacob Zuma. Image: Shutterstock

Why Journalists Must Hold Each Other Accountable to Protect Democracy

Anton Harber is a renowned South African veteran journalist and the Caxton Professor of Journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. During his career, he’s been the founder and editor of the anti-apartheid newspaper the Weekly Mail, now known as the Mail & Guardian, editor-in-chief of South Africa’s leading television news channel eNCA, and chief executive of Kagiso Broadcasting.

Harber now serves on the board of the Global Investigative Journalism Network and the Centre for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, and is the convener of the Africa Investigative Journalism Conference, the biggest annual gathering of some of the finest investigative journalists on the continent.

Veteran journalist and Campaign for Free Expression executive director Anton Harber. Image: Courtesy of Harber

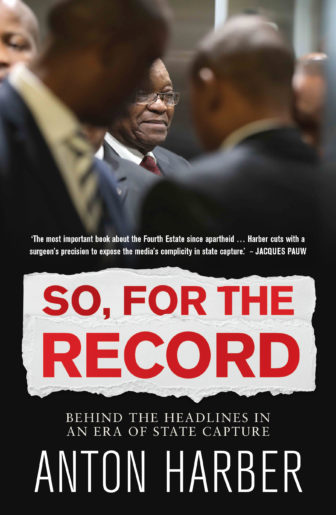

In this interview, Harber speaks about his latest book “So, for the Record,” the state of journalism in South Africa, and press freedom in the region. He also speaks about state capture in South Africa and the role played by leading media organizations.

State capture is an organized form of corruption by politicians and businesses to influence a country’s decision-making process for their own personal interests. Most countries have laws that seek to prevent state capture from happening. However, state capture directly involves weakening these laws and the state agencies that enforce them to pave the way to perpetuate these crimes.

South Africa’s former President Jacob Zuma was accused of colluding with the Guptas, three Indian-born brothers who moved to South Africa at the end of apartheid. The Guptas owned a portfolio of companies that enjoyed lucrative government contracts. In return, they employed several members of the Zuma family into senior positions. The revelations from the Zondo Commission of Inquiry, a judicial commission set up in 2018 to investigate allegations of state capture, corruption, fraud and the alliance between Zuma and the Guptas, led to the protests and political instability that eventually ended Zuma’s administration after he resigned in 2018.

Harber was vocal about state capture and frequently commented on it as a judge of the Taco Kuiper Prize for Investigative Journalism, a media award which rewards the best work and sanctions the worst.

Q: In your book, “So, for the Record,” you raised a number of issues about journalism in South Africa: from the influence of the Gupta family during state capture, to the highs and lows of investigative journalism in South Africa at this period. Could you please give us an overview on this?

Anton Harber: I was really struck by the highs and lows of South African investigative journalism, particularly during the state capture period. Certain investigative journalists played a very key role in exposing and helping expose and stop the period of extreme state-capturing corruption. There is no doubt that some very fine journalism played a key role in facilitating what we all knew was happening at that time. It wasn’t a surprise to us, but journalists provided the evidence that allowed it to be stopped.

Harber’s book, “So, for the Record,” details the threats of state capture in South Africa. Image: Screenshot

At the same time, there was journalism that enabled state capture, and one of the oddities was it was actually a group of some of our best-known investigative reporters who found themselves in a position where they got involved in various stories that assisted the state capture project. And I asked myself: Why did this happen? Did some people get it so right and some credible journalists get it so wrong?

And for the country’s biggest newspaper The Sunday Times, the country’s biggest newspaper, I thought it was time we investigate the investigators. As we hold everyone to account, we must also hold ourselves to account. So I decided to have a close look at what went wrong and what went right. Here’s what I wanted to understand: when things go wrong in investigative journalism, what lies behind that?

Q. In terms of the role played by these outlets during the state capture, do you think there was a kind of collusion by some journalists or media outlets to do these sets of stories they did at that period? Do you think they were bribed to do stories that favored the state capture or given some kind of contracts or other benefits?

AH: There is a strong suspicion that it’s possible that some individuals were bribed. But certainly not the whole team because I think there were some individuals who were just misled. But what I describe is a whole range of factors that led them down this path to buy into this narrative and to stick with it. When The Sunday Times reporting became totally discredited, they stuck with it and refused to back down for two years.

But I talk about the culture of that newsroom precisely, because it was the biggest, most powerful newspaper. It was that arrogance that allowed them to start cutting corners in a verification process. So the culture that developed in that newspaper was critical and it was also critical that it happened at the time when the paper was facing the challenge of the Internet and social media. The media world around them was changing and they were slow to understand how that change was impacting them.

This led them to do certain things like cutting corners in their reporting, which damaged their credibility and accuracy. I also pointed to a concerted effort by the state security agency to spread a false narrative to undermine their journalism and suspected of bribing some journalists by having them on their payroll.

There were a number of factors, but it starts with having a culture in the newsroom that allows them to cut corners on the process of verification and other normal checks and balances. They had an arrogance put up for many years even when they got things wrong. They were big and powerful enough to ignore that fact. But in an era of social media, you can’t ignore it and they were called to account in a way they hadn’t been in the past.

Q. Speaking about media accountability and in cases like this, what do you think other media outlets should do to hold their partners or colleagues accountable? What role do you think they should play?

AH: I believe we have to scrutinize each other and hold each other to account within journalism. Other newsrooms should not be scared to take on, to criticize, to even expose their colleagues because we all get damaged when somebody goes off track or when some journalists go off track. We all get damaged particularly at this time when journalism is suffering from credibility and trust issues. So it is important that we hold each other to account and try to expose anyone who gets things wrong and challenge them.

There used to be a notion that we didn’t criticize our colleagues in the industry. But I think they were protecting each other in a way that’s wrong. The best way is to hold each other to account, scrutinize, and examine each other.

Q. What is the state of state capture and what is the state of journalism in South Africa?

AH: I would say it hangs in the balance because our ruling party under President Cyril Ramaphosa supported the Zondo Commission of Inquiry after he took over. He set out to stop state capture and chase out those who were responsible. But his party is divided and therefore his capacity to do so has been hindered by the fact that his own position has been very vulnerable. So it hangs in the balance because the party is divided between those who would continue to work against state capture, against corruption, and the body that is fighting to depose him in order to be able to start a prison and continue on that path.

And while Ramaphosa is dominant at the moment, we are waiting to see if he stays dominant and whether he can see things through. Having said that, we had this commission which sat for two years and heard an extraordinary range of evidence that put it all out there and that exposed state capture. So Ramaphosa has played a very big role in exposing the horrors and the depth of what happened under the state capture and nobody can pretend it didn’t happen.

Q. And what’s the state of the media?

AH: I must tell you I am very concerned about the state of our media and the financial and uncertain pressures it faces. We certainly have pockets of excellence. We have some very good journalists, particularly investigative journalists who do great work. But much of the work that is being done now is not in the tradition or larger newsrooms but in specialist units like the AmaBhungane specialist investigative unit. Interestingly, it is not in the traditional newsrooms and we face a real problem, with some media that have gone completely rogue. They have broken with the press council and the press ombudsman and they are just publishing rubbish. This comes from a group that traditionally was quite a mainstream and a respectable group and is doing enormous damage to the credibility of journalism. So I am very worried about the institutions of journalism and their sustainability.

Q. The Campaign for Free Expression, the media nonprofit which you launched last year, has really been doing some work in advancing freedom of expression. What is the state of press freedom in South Africa and in this region?

AH: It is hard to generalize because you have South Africa and Namibia, for example, which have a great deal of free expression, and you have a number of countries in the middle like Botswana, with some degree of free expression but where it is also under attack. Then you have countries like Zimbabwe, where journalists are almost under constant attacks and where free expression is very seriously compromised and where journalists are beaten up and attacked.

We are a new organization and at the moment, we are focusing on four countries where we try to monitor the situation. Let me say we don’t only deal with media freedom. We deal with all free expression affecting all citizens and we are focusing on South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Eswatini as our first stage.

This is interesting because in South Africa we have a great deal of free expression protected by the constitution but we have a situation where it’s often under attack because of the uncertainty of our political future. We know that when a liberation organization is in danger or at the verge of losing power, the first thing that gets attacked is the media. So we are in a precarious time where we have to do a lot to defend the free expression we have.

We also know South Africa is grossly an unequal society. We all have the same right to free expression, but we don’t have the same access and capacity to exercise that right. So, there is a lot of work to be done to expand that right and to ensure everyone can exercise free expression in a country like South Africa. That’s different to say Zimbabwe, where we have to defend journalists from being beaten, jailed, or prosecuted. So, there’s a lot of work to be done across the region.

Q. Do you work alone or do you have other media advocacy partners you collaborate with?

AH: We work to create partnerships with other free expression organizations and also civil society organizations. So, for example, when we got involved in Eswatini, we worked with the Eswatini Editors Forum. We were involved in an intervention in Botswana and worked with the Botswana Editors Forum and the media institutes in South Africa and building coalitions and partnerships with them. Regional partnerships and coalitions are very important for us to support each other and react to what is happening in different parts of the world. In South Africa, we are talking to the big trade union junior organizations for example, to say let’s work together on how free expressions affect your members. We are at the moment talking to cultural organizations, artists, and writers that need their freedom protected and let’s work together on these issues. So, we see partnerships, coalitions, solidarity across the region absolutely centered on our work.

Q. What have been your challenges in fighting for free expression and how have you been able to address them?

AH: You know we are a new and small organization so we are pretty stretched and there is always an issue of resources to tackle these issues. I would say that we have to do a lot of work to make freedom of expression not just the media and journalists’ issue. We’ll only really secure freedom of expression when civilians in general put it in an ordinary agenda and are aware of the importance of freedom of expression.

A lot of work needs to be done to convince all kinds of citizens that this is an important issue. People are tempted to say: Why do I care about freedom of expression when I need the right to health, the right to life, and the right to decent housing, and the right to earn a decent living and these fundamental things? We constantly say that only the right to free expression equips and enables you to protect your other rights.

Q. What is the future of journalism in South Africa?

AH: It’s an uncertain future as it is in many parts of the world because we have gone through and we are still going through so much change and so many issues of sustainability. But there is no question in my mind that there will be a recognition that we need journalists more than ever and for that reason, we will find ways in which to fund it and make it happen and protect the space.

There is no question in my mind that forcing public accountability for those in power is more important than ever. And in a world where people are so bombarded with information, disinformation, and misinformation, the role of the journalist to help people find the facts, the truth and to understand the context in which things happen and the debates on the issues is more important than ever. Because of that, I think that solutions will be found whether it’s at the state level or at the individual level. There will be a recognition that one has to find ways to sustain and protect journalism.

This interview with Anton Harber was originally published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and is reprinted here with permission. Harber is a GIJN board member and executive director of the Campaign for Free Expression.

Additional Resources

Overcoming the Challenges to Investigative Journalism in Southern Africa

Award-Winning African Journalists Discuss Their Investigative Reporting Challenges

From COVID Scandals to Chemical Explosions: South Africa’s Leading Investigations from 2021

Patrick Egwu is a Nigerian freelance investigative journalist based in Toronto, Canada, where he is a journalism fellow at the University of Toronto. His reporting is at the intersection of human rights, social justice, global health, migration, and conflict and development in sub-Saharan Africa, and has been published by Foreign Policy, NPR, Daily Maverick, African Arguments, Rest of World, and elsewhere.

Patrick Egwu is a Nigerian freelance investigative journalist based in Toronto, Canada, where he is a journalism fellow at the University of Toronto. His reporting is at the intersection of human rights, social justice, global health, migration, and conflict and development in sub-Saharan Africa, and has been published by Foreign Policy, NPR, Daily Maverick, African Arguments, Rest of World, and elsewhere.