How They Did It: The Real Russian Journalists Who Exposed the Troll Factory in St. Petersburg

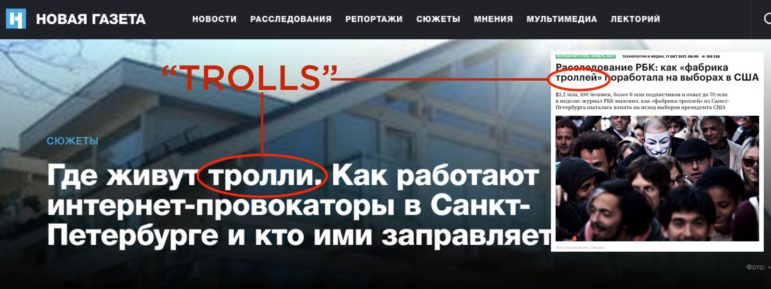

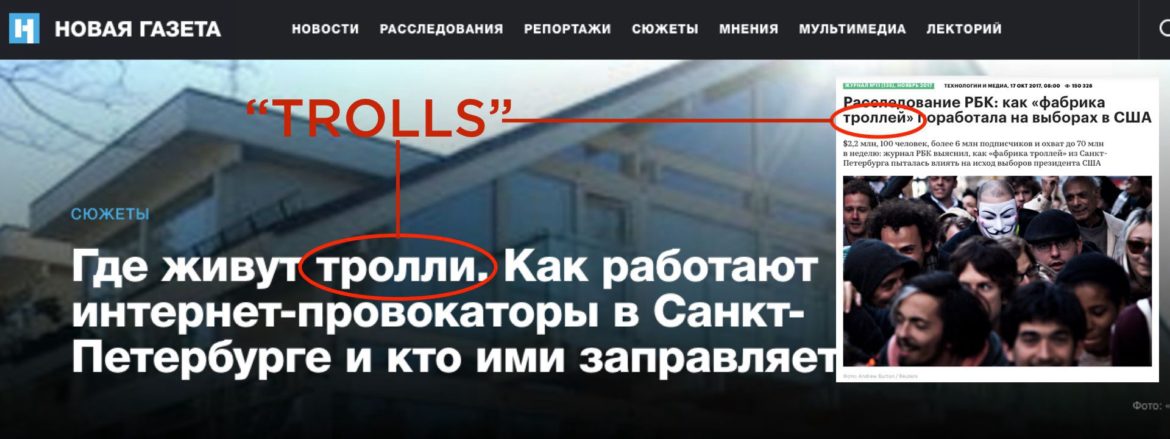

Headlines from Novaya Gazeta (main picture) and RBC (РБК, inset) exposing the “troll farm” in St. Petersburg.

The reason we know so much about the Russian information operations that targeted the United States from 2014 to 2017 is that some Russian journalists are very good at their jobs.

Special Prosecutor Robert Mueller’s indictment of 13 Russian citizens for conducting “interference operations targeting the United States” provided a wealth of detail on the workings of the so-called “Internet Research Agency” in St. Petersburg, from which the accused are said to have operated.

Yet many of those details were already known, thanks to the work of Russian investigative journalists. It was Russian journalists who first revealed the existence of the “troll factory” (its Russian nickname) in 2013, and Russian journalists who exposed the identities of its most effective accounts. While we mostly know the activities of the “troll factory” for its work around the 2016 American election, a number of Russian journalists uncovered how it mostly focused on influencing domestic opinion, especially with its early activities.

It was Russian journalists, too, who provided the sharpest insights into the workings of Kremlin propaganda outlets RT and Sputnik, disproving the outlets’ claims to be no more than journalists.

This post delineates the extraordinary work done by independent Russian journalists who provided so much detail on the Russian information operations.

Where the Trolls Live

According to Mueller’s indictment, the Internet Research Agency was registered as a Russian corporate entity “in or around July 2013.”

Mueller’s dating could have been more precise. On September 9, 2013, independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta (Новая газета) published an investigative piece headlined, “Where the trolls live. How internet provocateurs in St. Petersburg work, and who pays them.”

According to the Novaya article, the Internet Research Agency was registered in the Russian Unified State Register of Legal Entities (ЕГРЮЛ, Единый государственный реестр юридических лиц) on July 26, 2013.

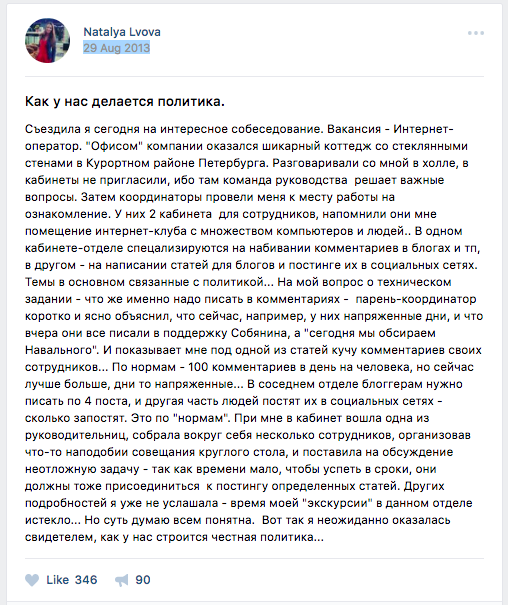

Novaya Gazeta’s article, by St. Petersburg correspondent Alexandra Garmazhapova, was one of three pieces that exposed the “troll factory” to the world in August-September 2013. The first was a post on social network VK by a woman called Natalya Lvova, describing how she had answered an ad to become an “internet operator” and came across a team whose job was to make political posts online.

According to Lvova, each team member had to write around 100 online comments a day, focusing on Russian politics:

“When I asked about the technical assignment — what exactly should I write in the comments — the coordinator guy explained briefly and clearly that now, for example, they are having a busy time, and that yesterday they all wrote in support of (Sergei) Sobyanin (then a candidate for re-election as mayor of Moscow), and ‘today we are slandering (anti-corruption leader and mayoral candidate Aleksei) Navalny.’ And he shows me under one of the articles a bunch of comments by his employees…”

Apparently tipped off by Lvova’s post, two journalists posed as job applicants and entered the Internet Research Agency: Novaya Gazeta’s Garmazhapova, and Andrei Soshnikov, of St. Petersburg local paper Moy Rayon (Мой район), who is now with the BBC’s Russian Service.

The two journalists described an organization that photocopied applicants’ passports as a matter of course, but then took no steps to verify their identities; an organization that was already divided into dedicated teams for different forms of online activity. As Garmazhapova wrote:

“A giant, snow-white cottage. A guard, secretary and offices with signs, ‘Management of bloggers and commentators,’ ‘Rapid reaction department,’ ‘SEO department,’ ‘Journalists,’ ‘Creative department,’ ‘Commentators’ department,’ ‘Bloggers’ department,’ ‘Social media specialists’ department.’ On the third floor, the management’s office and a conference room.”

Applicants were expected to write a short test to prove their abilities, as Soshnikov described:

“First task: write about the new law on education, and don’t forget to add keywords about Navalny!” the brigadier orders.

“What’s Navalny got to do with this?” I ask.

“Oh, it’s not Navalny. You see, we had a ‘situation’ recently, and, in general, we don’t give test tasks that are the same as at work. Write what you want. Write three days about the law, good or bad.”

The trolls were given specific metrics, posting around 100 times per day, and specific themes on which to write — including the G20 summit in St. Petersburg, held on September 5–6, 2013. Garmazhapova quoted the manager who interviewed her, Aleksey Soskovets:

“We have to raise the number of visits to a site. You can do it with robots, but robots work mechanically, and sometimes systems like (Russian search engine) Yandex ban them. That’s why it was decided to do it with people. Write comments from yourself according to the vector which we indicate. For example, on the G-20, you can write that it’s a great honor for Russia, but it’s uncomfortable to get home.”

Garmazhapova’s report made clear that the troll factory’s initial output was in Russian, and focused on Russian politics. Even at this early stage, however, its content attacked America:

“On the desktops there are screenshots of our predecessors’ work, attacking America and Navalny. Like, in the States it’s dark (because of the skyscrapers), people are selfish and greedy, and the movies are soulless, whereas our cinema is rising from its knees. Hundreds of comments, made up of pure cliches and stereotypes.”

The screenshots also immortalized troll attacks on the Russian edition of Forbes magazine in May 2013, suggesting that the troll activities had begun before the Internet Research Agency was registered.

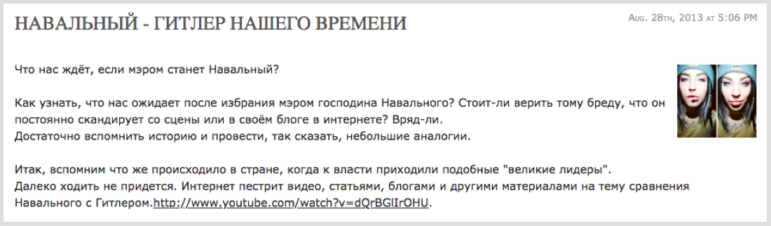

Soshnikov provided links to some of the LiveJournal posts trolls had made, such as the post below, calling Navalny “the Hitler of our time,” when he was running for the mayorship of Moscow.

The Hitler of our time: Troll factory post exposed by Andrei Soshnikov. (Source: LiveJournal/alexmonc)

Even at this stage, however, the “troll factory” seemed to struggle to find dedicated workers who took the job seriously. Soshnikov described a conversation with a fellow applicant:

“You can go crazy,” one says. “They told us we have to write four LiveJournal posts a day, write on city forums and comment in the media. Nobody upstairs reads our posts, I just copy texts from Wikipedia.”

Already, too, suspicion was rife — apparently inspired by Lvova’s post. Soon after Soshnikov left the building, Soskovets phoned him.

“You’re not a member of the opposition, are you?”

“No.”

“OK, I’m just interested in where people come from.”

These early reports are remarkable for both their timing and their daring. Russian investigative reporters, inspired by a VK post, exposed the main elements of the troll factory — its management, the fake social media accounts, blog posts and comments and the attacks on Kremlin critics — within weeks of the Internet Research Agency’s creation. They did so under their own names and in their own publications. This was journalism of a high order.

The Infiltrator

In 2014, the “troll factory” moved from “Olgino” to a new site, a four-story building at 55 Savushkina Street in northern St. Petersburg. By this time, the operation’s scale had grown dramatically, and hundreds of employees were working round the clock to keep posts going in both Russian and English.

In February 2015, the agency’s cover was blown: Soshnikov, then still with Moy Rayon, published a new piece from an unnamed whistleblower with photos, videos and copies of “technical tasks” given to the trolls.

On Camera: Video of trolls at work. (Source: Andrey Soshnikov/Moy Rayon)

Most of the tasks concerned Russian politics; the pages on the United States illustrated the themes the “troll factory” would attack with such vigor throughout 2015-17.

“The USA has several important internal problems. We single out three:

“The problem with the mass proliferation of weapons, and the corresponding mass shootings, crimes and incidents…;

“American policemen exceeding their authority in a way which has become commonplace. If, 20 years ago, a suspect could count on a preliminary investigation and immunity, now, on being detained, beatings and even killing have become routine business…;

“The Obamacare program, which provoked vast problems and discontent among American citizens…;

“The problem of the NSA and the total surveillance of American citizens by the intelligence services.”

The article reported that the “troll factory” had pulled out all the stops after the murder of Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov on February 27, 2015.

“When Nemtsov was killed, the work of the Kremlin robots changed: they stopped pouring on Ukraine (this is their routine everyday work) and were transferred to the murder…They said the same thing in different words: the murder is a provocation, the Kremlin has nothing to do with it, the opposition killed its own man to attract more people to the march.”

The story also traced the corporate ownership of the Internet Research Agency back to the Concord holding company, the property of Russian billionaire Yevgeny Prigozhin, who made his fortune through lucrative government contracts, and whose name tops Mueller’s indictment.

The source for these leaks was identified only as “Alexei.” Two months later, a whistleblower was named: activist and investigator Lyudmila Savchuk, who spent two months undercover in the “troll factory” in late 2014. In April 2015, she revealed her story, describing the working conditions in the factory’s Russian-language branch.

Whistleblower: One of Lyudmila Savchuk’s first interviews. (Source: YouTube/AFP)

“We had to write very positive comments about the government. We were given information and told how we should use it — for example, that life is more and more beautiful, and we’re living better and better. And if it’s about the US, we have to do everything to make the reader conclude that people there live badly, and that it’s not going well.”

Her account of her actions, given in interviews to outlets including Spiegel Online and the The Washington Post in June 2015, confirmed that the “troll factory” had grown in size and sophistication, but kept a similar style and structure.

“There are departments. Mine is responsible solely for Live Journal blogs and others are for commenting on the media. There’s also a group that masquerades as journalists. They operate fake news portals that pretend to be Ukrainian news sites, with names like Kharkiv News or the Federal News Agency. We had video bloggers. Some made themselves look like members of the Russian opposition.”

The “troll factory” spread its venom across multiple platforms:

“I have personally seen the following: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Livejournal.com as well as the Russian networks VK.com and Odnoklassniki. The targets also include the discussion areas on all major news sites and the forums of the websites of cities in the Russian provinces.”

Each unit received instructions on what to write, in different formats.

“It was different in every department. For us, they were written, via the intranet, and they were called ‘technical tasks.’ Those who were supposed to comment on media articles were given verbal communication about what they were supposed to write. One example of a key assertion that was to be disseminated was that Boris Nemtsov was himself responsible for his death.”

Crucially, Savchuk confirmed that the “troll factory” also had an English department, later to become notorious from Mueller’s indictment as the “Translator Project.”

“Most work in Russian, but I know that some also write English posts. Ukrainian also plays a major role. I also heard about German, but not in this building.”

Savchuk went on to sue the Internet Research Agency for employing her without a contract, and won a symbolic one ruble compensation.

Her whistleblowing, and the research by Moy Rayon and Novaya Gazeta, were crucial to our understanding of the “troll factory.” Three points stand out.

Her whistleblowing, and the research by Moy Rayon and Novaya Gazeta, were crucial to our understanding of the “troll factory.” Three points stand out.

First, the factory’s primary goal was to flood the Russian internet with pro-Kremlin propaganda. Estimates put the total number of trolls at 800–900; according to Mueller’s indictment, over 80 of those focused on the United States. This was a Russian political operation more than a foreign one.

Second, the “troll factory’s” ownership was clear even in 2015, and led back to Yevgeny Prigozhin, who was both a major government contractor and a friend of President Vladimir Putin.

Third, at the critical moment of Nemtsov’s assassination, the “troll factory” flooded internet fora with thousands of posts aimed at protecting the Kremlin.

Taken together, these factors all indicate that the “troll factory” was operating with the Russian government’s blessing. Given the tight control that the Russian government exercises over the Russian media, Prigozhin’s own close links with the Kremlin, and the speed with which the “troll factory” jumped to defend the government after Nemtsov’s death, it is implausible to suggest that it was operating without the government’s knowledge.

Exposing the Accounts

One of the tragedies of 2015-16 was that the “troll factory” was exposed so brilliantly in Russia, but ignored so utterly in the United States. It only broke in the broader public consciousness in January 2017, after US intelligence agencies named it in their report on Russian interference.

That exposure raised the general concept of “Russian trolls” into the public eye, but failed to identify specific accounts. It was not until September 6, 2017, that Facebook confirmed it had identified and deleted 470 “inauthentic” accounts which were “likely operated out of Russia.”

Three weeks later, Twitter confirmed that it had identified and suspended 201 accounts linked to the deleted Facebook ones. Neither network named the accounts involved.

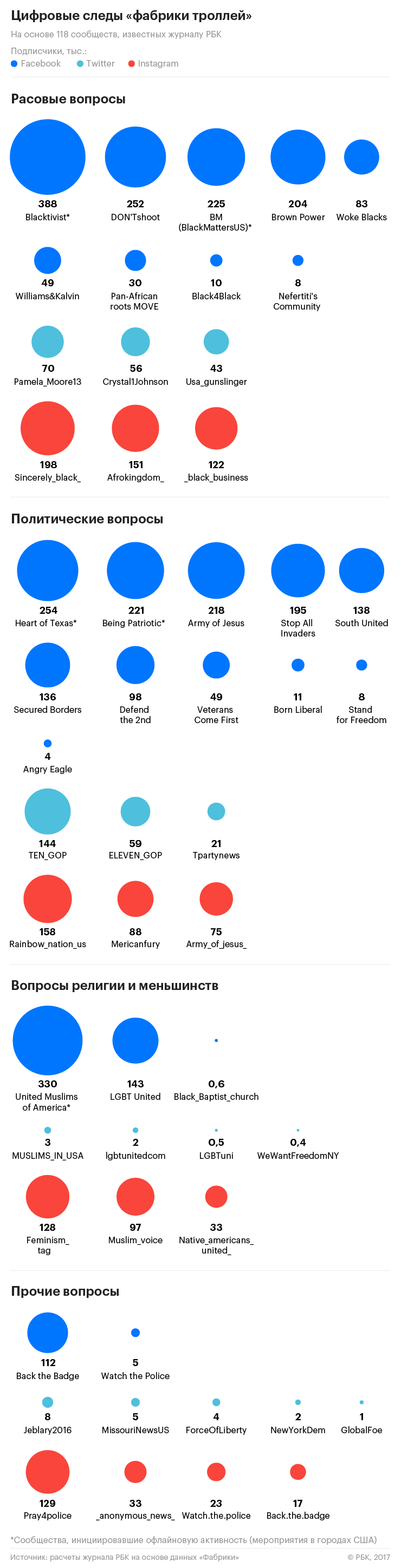

That task was left to another Russian outlet, RBC (РБК), and journalists Polina Rusyayeva and Andrei Zakharov (Полина Русяева, Андрей Захаров). On October 17, 2017, they published a detailed analysis of the “troll factory,” including a leaked list of its most effective accounts.

RBC’s post was a crucial resource for researchers. Twitter shared a list of 2,752 “troll factory” accounts with the House Intelligence Committee; the Democrats on the Committee published the list. Facebook published some of the troll ads and accounts in its presentation to the Senate Intelligence Committee on November 1, 2017. However, RBC remains the most comprehensive multi-platform summary of the “troll factory’s” activity.

Thus, the backbone of most public open source investigations into the Russian “troll factory’s” activity — as opposed to company internal ones — is the work of Russian journalists.

Not Just Anonymous Trolls

Three other Russian journalists deserve particular mention for their role in exposing Russian information warfare. They are Aleksandr Gabuyev, of independent daily Kommersant (Коммерсантъ), and Ilya Azar of newswire lenta.ru, who interviewed RT’s chief editor, Margarita Simonyan, in 2012 and 2013 respectively; and an unnamed reporter for state news wire RIA Novosti, who filmed the wire’s new chief editor, Dmitriy Kiselyov, when the wire was taken over and reformed as state propaganda agency “Rossiya Segodnya” in 2013. Sputnik is Rossiya Segodnya’s export brand.

These genuine journalists have given us the clearest understanding of how the Russian government’s network of pseudo-journalists work. Gabuyev was the first, asking Simonyan in 2012 why he, as a taxpayer, should fund RT.

“Well, for about the same reason as you need the Ministry of Defense,” Simonyan replied. She went on to compare RT with the army and said, “We were waging the information war against the whole Western world” during the Georgian war of 2008.

In one exchange, Gabuyev exposed Simonyan’s perception of her outlet as a weapon of state information warfare.

Question: Have any lessons been learned? Is there an anti-crisis mechanism? Is there any understanding that it is necessary to water, for example, the flower called Russia Today, so that it will grow into a mighty tree, and could be used as an information cudgel at need?

Simonyan: I think so.

Azar confirmed Simonyan’s mindset a year later, in an interview in which, again, she referred to RT in military terms:

“Of course, the Defense Ministry can’t start training soldiers, preparing weaponry and generally making itself from scratch when the war already started. If we don’t have an audience today, tomorrow and the day after, it’ll be the same as in 2008.”

Simonyan’s statements explicitly mark RT as an “information weapon,” rather than a journalism outlet. This remains evident from the broadcaster’s own behavior, and its long string of convictions for violating broadcasting standards; but it is thanks to real Russian journalists that we have the chief editor’s own confirmation of its purpose.

Much the same applies to Kiselyov, the only Russian broadcaster to be sanctioned by the European Union for his role in propagandizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea. On December 12, 2013, he addressed staff at RIA Novosti, a state-funded news wire which had previously won respect for its independence, but which had just been told that it would be dissolved and turned into Rossiya Segodnya.

An RIA Novosti journalist filmed Kiselyov’s opening speech to his new employees, in which he made clear where their loyalties should lie (translation by The Interpreter):

“We are a state agency which exists on government funds. I am not against other points of view, they can be diverse even within this field about which I am speaking. But if we are to speak about traditional politics, then of course we would like it to be associated with love for Russia.”

An RIA Novosti journalist asked twice how to separate love for the country from love for the government. Kiselyov replied:

“Separate your attitude toward the government from your attitude toward the fatherland. If you plan to be involved in subversive activity, and that does not coincide with my plans, then I will let you know directly.”

Conclusion

The story of the Russian “troll factory” is a story of real journalists exposing falsehoods. Russian journalists broke the story of the “troll factory,” and revealed its early workings. They first identified its ownership, and published its most important accounts. They provided the strongest proof that the Kremlin’s own “journalists” are nothing of the sort, but are, in their own eyes, engaged in an information war against the West.

This is a vital point. The trolls and pseudo-journalists who waged a propaganda campaign against the United States were Russians, but so were the journalists who exposed them.

The events of 2014-17 were not a question of Russians against Americans, or Russia against America: they were a story of Russian government outlets, and a “troll factory” whose owner had strong links to the government, attacking government critics both inside the country, and outside.

It is thanks to Russian journalists that we know so much of what went on.

This post first appeared on the Medium page of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab) and is cross-posted here with permission.

Ben Nimmo is a senior fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. His areas of research include social media, digital forensic research, digital engagement space, and open source information.

Ben Nimmo is a senior fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. His areas of research include social media, digital forensic research, digital engagement space, and open source information.

Aric Toler is the lead digital researcher for Eurasia at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. He is a former analyst with Bellingcat whose focuses include Russian-speaking countries, conflict investigation, and corruption research.

Aric Toler is the lead digital researcher for Eurasia at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. He is a former analyst with Bellingcat whose focuses include Russian-speaking countries, conflict investigation, and corruption research.