Image: Screenshot

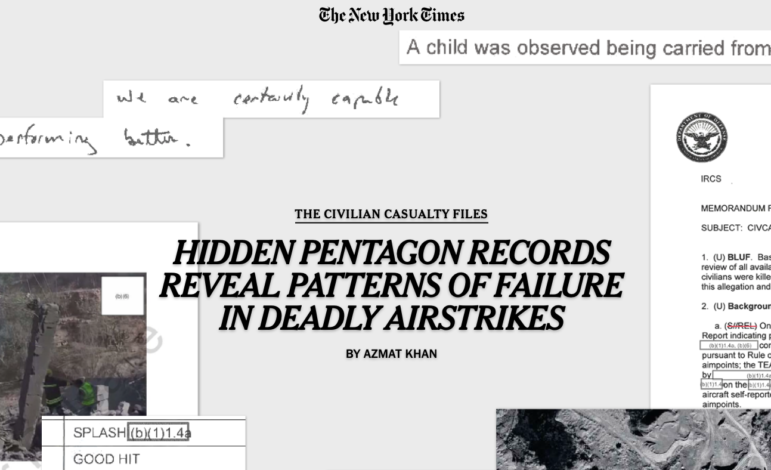

How the NYT’s Pulitzer-Winning Series Exposed Civilian Deaths in the Air War on ISIS

On March 18, 2019, a US fighter jet seeking ISIS terrorist targets dropped a bomb on a large crowd of women, men, and children near the town of Baghuz, Syria – and another coalition aircraft then dropped two more bombs on the survivors. Far away, at a US military air operations center in Qatar, one “confused analyst” monitoring drone surveillance typed “Who dropped that?” into the secure messaging system, according to The New York Times. The paper reported that about 70 people, including dozens of civilians, were likely killed in that single, catastrophic blunder.

On August 29 of last year, 10 people — all civilians — were killed by a drone-fired Hellfire missile launched into a courtyard in Kabul, Afghanistan. The target: a man — later found to be an aid worker — who had been tracked by a Reaper surveillance drone and seen loading objects into a car that were wrongly interpreted by distant analysts as bomb parts.

These were just two of more than 1,300 incidents of alleged civilian casualties examined by a team at the Times in an exposé on the US-led coalition air war against ISIS in the Middle East since 2014. Based on its exhaustive analysis, the Times concluded that “the American air war has been plagued by deeply flawed intelligence, rushed and imprecise targeting, and the deaths of thousands of civilians.”

The newspaper’s damning, eight-part series sent shockwaves through the US Department of Defense and, earlier this month, won the Pulitzer Prize in the International Reporting category. In its citation, the Pulitzer board lauded the “courageous and relentless reporting that exposed the vast civilian toll of US-led airstrikes, challenging official accounts of American military engagements in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.”

One important approach to this investigative field was pioneered by journalists and researchers from two UK-based nonprofit groups: The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) — a GIJN member organization which has used public documents, press reports, and some original sources to track drone strikes in the Middle East since 2010 – and Airwars, a watchdog that has used a wide variety of sources, including Arabic-language social media and NGO reports, to document civilian casualties from airstrikes and artillery in the region since 2014. The Times investigation was based on ground reporting at the locations of more than 100 civilian casualty sites in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, interviews with military insiders and witnesses, leads from databases like Airwars, and an analysis of a trove of confidential military assessment documents obtained through the US Freedom of Information Act.

The Times revealed two mutually-reinforcing errors among many strike planners. The first was confirmation bias, in which everyday objects and activities were often misinterpreted as the kinds of weapons or suspicious movements that preoccupied strike officers. The second was contextual ignorance, where flawed “patterns of life” theories were used to predict civilian movements, and little attention paid to behavior tied to predictable events like Ramadan, midday heat, and civilians ordered to move by ISIS fighters.

(Hear reporter Azmat Khan discuss how these biases affected US airstrike targeting in the clip below.)

Likewise, the Times uncovered similar bias and incompetence in the casualty review process. Casualties in several towns were not assessed at all because military reviewers either confused them with other villages with similar names that were not targeted, or claimed they could not even find the towns on their maps. For instance, reviewers abandoned an inquiry into a claim about 30 deaths in the Mosul neighborhood of Siha because they could not find a place with that name – but the Times team quickly found it listed as “Sihah” on Google Maps, and also found news reports with the “Siha” English spelling with simple Google searches. Likewise, Pentagon officials dismissed claims of civilian deaths at a place in Iraq called “Al-Bab Al-Gharbi,” because they looked for – and failed to find – two separate locations called “Al-Bab” and “Al-Gharbi.”

The Pulitzer Prize Committee noted Azmat Khan’s role as contributing writer in its 2022 award to the Times for International Reporting. Image: Courtesy of Khan

After the blockbuster series won the Pulitzer, the reporters even earned a rare compliment from the US military itself. “I cannot say that this process was pleasant,” Pentagon Press Secretary John Kirby said in response to the Times’ award-winning coverage. “But I guess that’s the whole point. It’s not supposed to be. That’s what a free press at its very best does. It holds us to account.”

To get a behind-the-scenes look at their investigation, GIJN interviewed two key members of that team: Christoph Koettl – a member of the Times’ visual Investigations team, who worked the initial Kabul drone strike story in September – and the series’ lead reporter, Azmat Khan, an investigative journalist at The New York Times Magazine and assistant professor of journalism at Columbia University. Khan has been digging into civilian airstrike casualties in the Middle East since 2016, when she and a sociologist – interviewing both military officers and witnesses on the ground – investigated 103 airstrikes in a sample area in northern Iraq, and concluded that one in every five so-called ‘precision strikes’ resulted in a civilian death. Khan says this rate was 31 times higher than what was claimed by the Pentagon – and that the same rate has persisted in “tens of thousands of strikes” ever since.

Weak Reviews and Strong Video Evidence Triggered the Series

One key takeaway from the Times reporters was recognizing the journalistic potential of unfamiliar documents. Having obtained just a single Pentagon civilian casualty assessment report for a strike in northern Iraq in 2016, Khan says she grasped two interesting features about this class of document: It contained an unexpected wealth of detail on the military communications involved, yet included little scrutiny or understanding of the communities being bombed.

“I was blown away by what I read in that first document — saying things like ‘We saw people opening gates,’ which [the US military] called an ‘ISIS tactic’… They said they filmed during the hottest hours of the day, but they saw no women and children – as though they would be outside at that point,” explains Khan. “I knew I had to get more of these documents.”

(Khan explains the origins of her reporting on civilian casualties in the clip below.)

In response, Khan began filing freedom of information requests, and a lawsuit, for many more of these Pentagon casualty assessments. And, by last year, she had amassed 1,311 similar reports. The team launched its series last September, after Koettl and his team stumbled upon security video of events prior to the August Kabul drone strike, which killed seven children. It showed that a beloved NGO aid worker, Zemari Ahmadi, had been wrongly targeted because he’d collected a laptop for his boss, and water canisters for his family — harmless behavior that military analysts, in a matter of minutes, had wrongly concluded marked him as a terrorist.

“Zemari’s coworkers told us how he was this regular guy who came in the mornings to fill up his large water canisters,” Koettl recalls. “We hadn’t heard that before, and it was super-interesting, because the military talked about seeing a man loading large packages into a car that they thought was a bomb. So we asked if they had any pictures of these canisters, and that’s how we learned they had all this incredible security footage.”

Christoph Koettl, visual investigations team member at The New York Times. Image: Courtesy of Koettl

The Pentagon changed its initial “righteous strike” claim in response to the story, admitting the mistake, but then claimed the attack had still been justified because Ahmadi had parked next to an ISIS “safe house.” Koettl’s team quickly disproved that claim too – showing the “safe house” was, in fact, a family home. “Christoph and the visual investigations team’s reporting on the Kabul strike I think woke the world up, and forced a lot of eyes on the subject,” Khan says, adding, “It’s hard to make civilian casualties an editorial priority.”

While there has been little military accountability in the wake of the series, and only small indications of reform, Khan says lasting impacts from the project include its methodology model, and the assessment documents the team made open for other reporters to dig into.

“You won’t see the kinds of change you’d want from institutions like the military overnight, but where I draw hope is that the public is far more aware of these shortcomings,” Khan says. “A lot of researchers are now poring over the documents we made public to really look at things like the laws of war, where reporters are not well placed to look.” Another impact, Khan suggests: “We’ll now see news media be far more skeptical about claims of military precision in the future and work hard to uncover these casualties.”

(Hear Khan talk about how the Times series could influence future investigations into civilian airstrike casualties in the clip below.)

Having reviewed Khan’s file, Koettl says his team noticed a series of “little mistakes with serious consequences” in military decision-making, and found evidence of systemic problems.

“What we noticed is that there are actually many military review people who do have the skills and the tools — they even list the tools they use in the documents: Google Earth; Wikimapia; all the tools that we use,” he explains. “But I think there is a turnaround of military personnel every few months, so there is no consistency, insufficient training, not enough language skills. It comes down to individuals, and how much they care.”

Khan says she verified casualty claims by matching GPS coordinates from assessment reports to satellite evidence and witness testimony on the ground, and also by closely monitoring strike videos posted by coalition forces.

The Times used Maxar satellite imagery to compare images before and after airstrikes in Syria. Image: Screenshot

“Before I’d go out in the field, I’d do a before-and-after satellite imagery analysis of the coordinates, and I’d put it in a document,” she says. “In the beginning, I was using [satellite imagery service] TerraServer; later, I used Maxar and Google Earth — looking for changes, and whether they matched what was described in the documents.” Khan adds: “For the witness interviews, I had to be careful not to lead witnesses with information from the documents, because people might tend to just confirm.”

Useful Databases for Civilian Casualty Investigations

While useful civilian death toll reports and so-called condolence payment records have been generated by organizations like Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and British medical journal The Lancet, Khan suggests that reporters start investigating airstrike casualties with dedicated databases that rely on multi-level sources — from public military statements to local-language social media and NGO reports. In particular, she recommends these sources:

- Airwars. Run by a UK-based NGO, this resource has collected data since 2014 on 60,000 claimed artillery and airstrike-caused civilian deaths across six countries, including Syria, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen. Its database includes thousands of military documents, NGO accounts, and Arabic-language news and social media reports, as well as graded assessments, and clear notations on verification limits and propaganda sources. “Airwars is incredibly useful to journalists internationally because they’re not just logging US military statements, but also looking at whether France, for example, might have been involved in a strike on this or that day; information on coalition partners like Australia, The Netherlands,” says Khan. “It’s tough getting access to some of these areas; or when you don’t know where the locations are, because the military doesn’t reveal them — that’s where Airwars was really helpful.”

- Drone Wars database. Compiled by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), this database focuses on coalition airstrikes in Afghanistan, Yemen, Pakistan, and Somalia since 2010. “TBIJ is great because you can easily download data on Yemen, Afghanistan, and others, and you can read their methodology,” explains Khan. “They have approximate geolocations in there, and what was admitted by militaries, and what wasn’t.”

- Wikimapia. While not a casualties database, Khan says this partially crowdsourced web map tool is useful for finding overlooked casualty sites, because it features some community-generated incident descriptions, and often includes labels and alternate place names that are not included in formal or Western maps. She suggests using it in conjunction with Google Translate, or the input of colleagues with local language skills. “Input differs by country – Wikimapia was used a lot in Iraq, but less in some other countries – but it was so helpful,” notes Khan. “I recall looking into a bombing of an electricity substation in West Mosul, and seeing that this substation was labelled in a certain way on Wikimapia. And I thought, let me just Google this with ‘Mosul’ and ‘airstrike’, and up came this really grim YouTube video of the incident, and I could verify it.”

However, Khan warns that even excellent, document-based databases contain significant gaps, due to factors like a lack of internet access, faulty military assessments, and missing or nonexistent government records — and that on-the-ground reporting is essential to avoid significant undercounts.

“For instance, I truly believe we do not have a sense yet of the full scale of civilian airstrike deaths in Afghanistan, especially in the south, and in the east — in Nangarhar and Kunar provinces,” says Khan. “In one village I spent almost a month in, sampling cases, after the fall of the government, no one there had death certificates. They were, like: ‘What are those?’ So, without official documentation, they won’t get counted. I had to go door to door.”

Tools for Gathering Airstrike Evidence and Sources

- VisualPing. Khan used this tool for monitoring changes to websites, for tracking strike videos that coalition forces posted or removed. “This is a tool I really liked — you can easily customize it to alert you to specific site changes you’re interested in,” says Khan. “I could then match my evidence to videos that the military had uploaded. I’d ask them, ‘Did you conduct an airstrike on this place?’ and sometimes they’d tell me ‘no.’ That was how I was able to uncover that they weren’t logging all of their own coordinates.”

- Google Earth Pro. Khan and Koettl say the desktop version of this well-known, free satellite imagery and mapping tool has improved its search features — for the Middle East, in particular — in the past six months. It now allows precise, before-and-after image downloads of airstrike scenes, using the tool’s time-lapse slider feature. “The one tool I use every day is Google Earth,” notes Koettl. “It was extremely important for the Kabul drone strike story. People underestimate it a little, thinking you can just zoom in and that’s it, but you can really use it to organize chronology and information on a map, and also share data with colleagues.”

- Searches on LinkedIn and military chat forums. “I shouldn’t give this tip, because it’s part of ongoing reporting, but you would be very surprised at how many jobs in this air war field are advertised on LinkedIn,” says Khan. “I built a database of some of these jobs. I like to hand-write letters to people I find there, so there is no digital trail.” Khan says reporters should also be on the lookout for civilian advisers and consultants to the military. “One former Pentagon adviser who studied these military assessments and pursued accountability was courageously public in our investigation,” she adds. Khan says another useful approach to identifying potential contacts is to participate in online military forums, and to scan comment threads. “It’s amazing how often you see people saying ‘I was there when…’”

- Teach war zone contributors to switch on location services. Khan says the verification value of a lot of airstrike site imagery bravely shared by local contributors can be lost because the metadata functions on their device are not enabled. “If you’re looking at a place like the Congo — sometimes it can be as simple as empowering people to use tools to document their own experiences and share them with you,” she says. “Maybe showing people how to turn on GPS coordinates on their phone, so their metadata is tracking.”

When asked if any air war victims had responded to the news of her Pulitzer win, and the renewed attention to civilian airstrike deaths it has garnered, Khan did not offer any sense of vindication or celebration. Instead, she shared a chilling reminder of the lasting damage left by ISIS and the US-led coalition’s war against it.

“I got a message from one of the Kabul strike survivors a few days ago,” she says. “He lost his daughter. He said ‘We’re still in Kabul, we haven’t been evacuated, we haven’t gotten any [compensation] money.’ He said: ‘Congratulations on winning this award — how much money are you getting?’”

“Hearing that,” Khan adds, after a long pause, “just is the worst part of the job.”

Additional Resources

How to Expose Lies from the Skies Using Satellites and Drones

Lessons Learned from Syrian Journalists Investigating Russian War Crimes

How to Use Data Journalism to Cover War and Conflict

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.