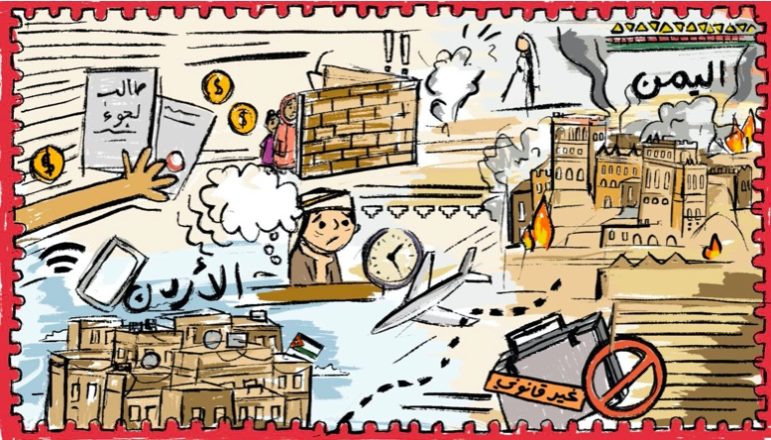

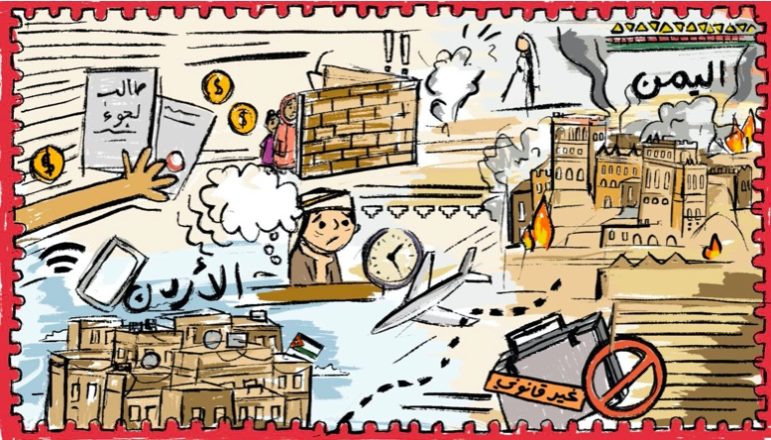

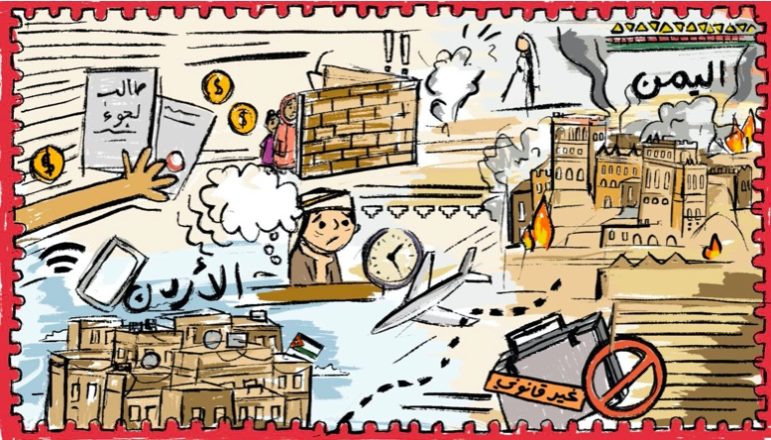

Illustration: Abeer Anabtawi, courtesy of 7iber

Jordan’s 7iber: From Citizen’s Blog to Watchdog Journalism

Read this article in

7iber, which began as a blog in 2007, has evolved into an online magazine that digs into under-covered issues in Jordan, including the plight of Yemeni refugees. Illustration: Abeer Anabtawi, courtesy of 7iber

Over the past 15 years, the Jordanian magazine 7iber (pronounced: heh-ber) has taken several journalistic forms. 7iber, which translates as “ink,” was founded in 2007 as a citizen journalism blog to meet a demand for news outside of the official narrative found in traditional newspapers. Over the years, this blog, which started as a volunteer effort, evolved into a professional media site, and then into an online magazine that strives to provide readers with information and reporting free from government influence.

Today, 7iber is still run by its co-founder, Jordanian journalist Lina Ejeilat, who is also a lecturer at the Jordan Media Institute and was formerly a Reuters reporter in the Jordanian capital, Amman. According to Ejeilat “the magazine’s editorial team has grown to 12 editors, journalists, and multimedia producers,” who work from the magazine’s office in Amman.

The site was recently selected as one of the newest members of the Global Investigative Journalism Network. GIJN interviewed Ejeilat, alongside one of the magazine’s senior journalists, Dalal Salameh, and Rana Sabbagh, the senior Middle East and North Africa (MENA) editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), to understand 7iber’s journalistic history and its role in the region.

While Jordan stands out as a country where the press enjoys more relative independence than in most of the MENA region, it still ranked 120th out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ 2022 World Press Freedom Index. And in its annual assessment, the organization noted that media professionals in the country continue to “censor themselves and respect the implicit red lines around certain subjects” and that the media face a number of other obstacles to independence, including “close surveillance by the intelligence agencies.”

Jordan stands above most of its peers in the MENA region in press freedom, but was still ranked a dismal 120th out of 180 worldwide in the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index. Image: Datawrapper

Information, Knowledge, Stories

“Since we started, the site has gone through different stages and changes because it started in the blog community that was blooming at the time,” explains Ejeilat. “The writers on the site were not involved in a rigorous editorial process, they were initially writing testimonies, opinions, personal experiences, and things that were published as blogs.”

Back then, those who ran the site felt that they could create a platform that would combine the strengths of a blog with some journalistic elements. The site’s development was tangible, but not rapid. In parallel, 7iber carried out offline activities, hosting writing and photography meet-ups and interactive public discussions.

Within four years, Ejeilat said the site reached the peak of the citizen journalism ideal. “We had more writers and citizens sending articles, pictures, and ideas. We organized debates on issues related to reform and political change,” she recalls. But this era was short-lived. “The momentum that initially accompanied the wave of protests and uprisings was met with the triumph of reactionary powers and there was a change in the political climate… In addition, social media platforms took over and the role of blogs declined,” she said.

The platform took on a different form in 2012, soon after the start of the Arab Spring revolutions in Jordan’s neighboring countries. (While there were some small protests in Jordan, it did not experience large-scale political upheaval.) This new approach was based on the fact that, as Ejeilat says, in this area “knowledge and information are what is missing.”

Jordan was the first Arab country to enact a Right to Information law, but the country’s commitment to transparency continues to offer a series of challenges. Most notably, the fact that much of the state’s conduct is shielded behind blanket classifications of being “security sensitive,” so government institutions won’t release much to reporters.

“There are significant problems in accessing information,” Ejeliat says. “In some cases, information is not classified properly for researchers and journalists to access, and, there is a dominant culture in the state apparatus that tries to treat most of the information as confidential and sensitive, but we deal with this by using available information that is not exploited in journalism to the fullest extent possible.”

Breaking Barriers, Facing Backlash

Since its evolution into a professional news site a decade ago, 7iber has conducted a series of far-reaching investigations, often focused on issues overlooked by mainstream media. Among them is the 2019 story Four Generations of Pakistanis in Jordan: Stuck Between Two Homelands. This exposé revealed that generations of Pakistanis have been living in Jordan since the 1960s, residing in crude huts made of wood and plastic on the outskirts of the farms where they work. These communities are essentially invisible to most Jordanians, and almost never receive any media coverage. The reporter visited these marginalized communities to understand how they have lived in the country for decades without having any citizenship rights or easy access to educational opportunities for their children.

Another 7iber investigation, Dwellers in Petra caves: When Planners Marginalize People’s Needs, revealed that successive governments had undertaken a campaign to expel local people living in caves near Jordan’s high-profile tourist areas. The government’s plans were formulated without a real partnership with the community and the alternatives provided did not meet people’s real needs.

This work has earned them recognition from those working in the region. “I have been personally following 7iber’s development since its founding in 2007, and the magazine stands out for its in-depth coverage of important issues that are not covered by traditional and non-traditional media in Jordan,” says OCCRP’s Sabbagh. “7iber magazine has its own writing style. The magazine’s investigations and reports are deep while also being enjoyable, smooth, and readable. 7iber is characterized by high autonomy, in a country where editors, regardless of their rank, are demanded to take a clear stand either with or against the government, and there is no way to stay independent and exercise the role of the Fourth Estate.”

Indeed, Ejeilat says that the magazine must still navigate the Jordanian government’s many red lines about what it deems acceptable news coverage. These official and unofficial restrictions are not limited to the royal family, but are often broader, she says. Because of Jordan’s unique geopolitical role in the region, she says there are very few purely domestic issues, meaning coverage that could affect allies such as the United States or some Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates can also present threats of censorship or worse.

Back in 2013 and 2014, 7iber experienced just such a crackdown. During that period, the Jordanian government blocked 7iber several times because the site had refused to be licensed in accordance with the country’s amended Press and Publications Act of 2012. 7iber’s management was — and continues to be — against this licensing requirement, calling it an obvious tool for censorship and control of the media. However, after a prolonged fight, the government charged 7iber with running an unauthorized press institution. 7iber ultimately lost the case and had to pay a fine.

“By the end of 2014, we came to the conclusion that continuing to work required licensing,” Ejeilat says. “The government’s goal was to make it difficult to create more websites, then they came after social media through the Cybercrime Act, and attempts by the authorities to control public debate and shrink the space available to it continues.”

7iber’s investigation into a government campaign to forcibly expel locals living near tourist areas in Jordan has drawn praise. Image: Screenshot

Surviving In a Hostile Environment

Since evolving from a blog network to a professional news site, 7iber has benefited from a donor network that includes the Open Society Foundation, the European Endowment for Democracy, Denmark’s International Media Support, and the Dutch and Swiss embassies in Amman. While Ejeilat chooses not to disclose the site’s annual budget, she says 7iber also brings in money via other revenue streams, which include providing editorial services and training programs.

“We are currently working on a new business strategy because it’s very important to us to reduce dependence on grant funding,” says Ejeilat. “Our main accountability has always been to our readers, not funders, and this is why it’s crucial for us to develop new revenue streams, including a membership program that we will launch soon.”

7iber journalist Dalal Salameh says the mainstream press in Jordan lacks a real investigative tradition. A pattern of breaking news coverage associated with real-time events prevails, which is often carried out quickly and without depth or real research into the background or context, she explains. It is this gap that investigative journalism from 7iber is meant to fill.

Salameh was once a teacher but moved into journalism, first by working for a local weekly news magazine. She later pivoted towards investigative journalism as a reporter at As-Sijil a prestigious, now-closed Jordanian magazine, and the newspaper Alghad, one of the most prominent outlets in the country.

“The editorial team selects investigative ideas from issues affecting people’s lives, which can be of interest to a broad audience,” Salameh explains. They try to focus on questioning the performance of power, in its various forms, the government, private sector, and civil society organizations. “We also focus on addressing issues that have not been truly covered in the media.”

Perhaps the most significant difficulty in 7iber’s investigative work is the intense challenge of obtaining relevant data and official information. This lack of transparency is due to several factors from rampant state secrecy to primitive, paper-based archival systems, to a general absence of recordkeeping. “If a detailed piece of information can not be found, we make a point of explaining it to the reader,” Salameh says. “In other words, the report will state that there is specific information that we were not able to get, and we explain why.”

Besides the difficulty of accessing information, another challenge for reporters is the country’s relatively small size, which makes building sources within the state apparatus more difficult because it is much easier to identify insiders and whistleblowers. This, in turn, makes it harder to convince other sources to speak. Still, Salameh has had success uncovering stories of those normally overlooked by the nation’s traditional media, like her exposé on the plight of Yemeni refugees in Amman.

This has prompted 7iber’s investigative team to be resourceful and creative, and to look for insightful, alternative sources. This might be a former official in the sector, now retired, who no longer has ambitions or professional and political concerns. “I also find that a lot of information and data that officials refuse to provide can be found in scientific studies,” Salameh explains. “Because it is known that information is usually withheld when it is for a journalistic purpose. But there is some leniency when the purpose is scientific research.”

Still, Salameh emphasizes that building and employing this diverse pool of sources for investigations is a years-long process — and it is based on a foundation of trust. “Sources will always be willing to collaborate when they see that their words have not been distorted or misused in an undesirable context, when they see that we did not publish parts they asked to leave out, and respected their wish to stay anonymous,” she says. “It is a cooperation that could in the future link you to other sources.”

In her view, this resource base must be diverse and not only include government officials, technical experts, and academics, but “ordinary” people from all walks of life as well. In other words, those whose lives are often the most impacted by misconduct, corruption, or other wrongdoing.

Commitment to Watchdog Journalism and Accountability

The goal of 7iber’s coverage, Ejeilat says, is for readers to understand the context and dimensions of the topics they cover comprehensively, so they can form an opinion based on solid evidence. The audience’s understanding, she adds, should not be arbitrary or influenced by the noise of discussion on social media. “We give the journalist two months to work on a story to get to the heart of the subject, and it often happens that while working on the story, new questions are triggered, and they are given more time,” she notes. “This space is very important.”

“Any press organization that wants to do investigative journalism should know that this is time-consuming and will not work out for sites that rely on daily news, high traffic volume, and advertising,” she advises. “Journalists must be in a constant state of development, trying to build a deep understanding of the subject, and obsessively fact-checking in order to provide readers with reliable material that captures the nuances and complexities of the issues that matter to them.”

In the end, the idea of holding the structures of dominant power accountable and delivering critical discourse while contributing to building a knowledge base for readers in Jordan and the region is at the heart of 7iber’s mission, Ejeilat explains. “We believe in a practice of journalism situated in the social sciences and humanities, in the sense that journalism isn’t just a technical craft,” she says. “We are trying to work on what we consider missing and to help grow the idea of long-form magazine journalism in the region.”

This story is the latest in a series looking at investigative journalism in the Middle East and North Africa region.

Additional Resources

‘Reporting from the Outside’: Lessons from Investigative Journalists in Exile

Reporter Katie McQue’s Tips for Covering Migrant Workers in Arab Gulf States

Reporting on Migration in the Gulf: A GIJN Guide

Ahmad Haj Hamdo is a Syrian journalist. A media graduate of Damascus University, he has published stories with Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, Daraj, the Guardian, and other media outlets. He is co-founder of Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), a GIJN member focused on training Syrian journalists.

Ahmad Haj Hamdo is a Syrian journalist. A media graduate of Damascus University, he has published stories with Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, Daraj, the Guardian, and other media outlets. He is co-founder of Syrian Investigative Reporting for Accountability Journalism (SIRAJ), a GIJN member focused on training Syrian journalists.