The GIJC23 panel on Women in Investigative Journalism featured a range of veteran and accomplished women reporters and editors. Image: Smaranda Tolosano for GIJN

The Afghan editor Zahra Nader remembers being told by a fellow reporter that she would “never be a good journalist — because you’re a woman.” When she was juggling the demands of work and being a new parent, Kenyan-based journalist Purity Mukami was asked to choose if she was a data scientist or a mother.

These are anecdotes from earlier in their careers, but even now, women in many parts of the world have to overcome steep hurdles and ingrained biases to work in investigative journalism.

“We still face different challenges than men,” said GIJN’s deputy director Gabriela Manuli, in a panel session at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) in Gothenburg, Sweden. “This is why we’re trying to see how we can support each other.”

During the session Oksana Brovko, CEO of the Association of Independent Regional Publishers of Ukraine, Gina Chua, executive editor at Semafor, Purity Mukami, data journalist at OCCRP, Kamilla Marton, journalist at Direkt36, Jessica Ziegerer, journalist at HD-Sydsvenskan, Hui (Lulu) Ning, journalist and editor at Initium Media, Zahra Nader, editor-in-chief of the Zan Times, and Emilia Díaz-Struck, the incoming executive director at GIJN, shared experiences that highlighted the importance of building supportive networks and creating communities of support. Here are some of their tips.

Diversify Your Newsroom

“The group of people who decide what we are focusing on used to be men — but this is changing,” said Semafor’s Gina Chua, who shared her own experience of being a trans woman in a typically cis male-dominated industry. Her advice is for outlets and newsrooms to diversify so they can broaden their collective knowledge about what they are reporting on. “We all have blind spots,” she said, “and the only way we solve that is by having more diversity at the table.”

Keep Going — and Support Others that are Struggling

“In some parts of the world it is harder to be a female investigative reporter than in others,” Manuli notes, as Brovko and Nader shared the difficulties of working in Ukraine and Afghanistan, respectively. Brovko talked about her experience as a mother and an investigative reporter in a country where many of her male colleagues went to war. “We are tired and we are wounded,” she said, “but we have a strategy.” With the support of female colleagues working in investigative journalism in Ukraine right now, Brovko said it is possible to continue the work she and her colleagues are doing.

For her part, Nader said women journalists in Afghanistan — and those reporting from the outside the country — are carrying a lot of trauma when reporting on the dire circumstances for women since the Taliban took over. “I don’t know how to give up,” she said. “That’s why we keep going.”

Mentors Make a Difference

One common insight: the importance of having a mentor. “It takes the power of collaboration to help us thrive,” said Díaz-Struck, who in her previous role worked on a number of collaborative projects at International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). She added that mentoring can be a way of growing not only personally, but also as a network.

Mentors can appear organically, some of the panel mentioned, and can provide important guidance, support, and act as a cheerleader for important stories. Some pointed out the difference in having a woman as a mentor, compared to a man. “Every mentor is useful and important, but it’s a very distinct experience” having a female mentor, said Mukami, who shared how a chance meeting with a woman at a conference helped lead her career path first into data journalism, and then investigative journalism. Having such a mentor, she said, is “like standing on someone’s shoulders who helps you climb over a fence.”

From left to right: Zahra Nader, Hui (Lulu) Ning, Jessica Ziegerer, and Purity Mukami. Image: Smaranda Tolosano for GIJN

Challenge Your Inner Impostor

Kamilla Marton works at Direkt36, a nonprofit investigative journalism center in Hungary. Despite early career successes, she started to struggle with imposter syndrome — a feeling she was not good enough to succeed. Her practical tips: first, acknowledge the problem. For her the key moment came when she was walking to work one day and realized that her self-doubts were close to sabotaging her own career. Her second tip is for reporters to stop comparing themselves to others. Instead, she advises those feeling this way to ask for feedback from editors and colleagues, which can help, and to talk about the issue.

Ning, editor of Initium Media, headquartered in Singapore, said that after being promoted overnight to a leadership position, she needed to overcome fears that she would not — and could not — succeed. So she developed a self-help strategy that breaks down what you are afraid of, what you cannot control, and lastly, the things you are able to influence and change. “That way you recognize the fear, but it’s no longer the center of your attention,” she said.

Audit Yourself and Set Goals

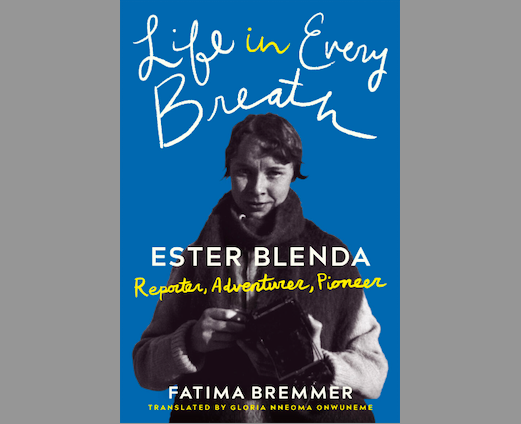

Sweden’s first investigative reporter, Ester Blenda, began her groundbreaking career by going undercover to expose the conditions on the country’s farms a century. But when Ziegerer and her colleagues carried out an audit on their department’s investigative collaborations, they found the vast majority had been with male reporters. So they developed a strategy and set a goal: within a year 40% of these partnership needed to be with women, the same gender balance as they had in their newsroom. “It was not difficult to achieve this goal at all,” she explained. What happened is that the focus of their work shifted: new investigations into topics like social services, the housing market, schools, even the horse industry, started appearing on their pages. “And today, it’s not just a goal — it is a natural part of our work.”

Don’t Let Others Define What You’re Capable Of

A unique experience women in highly patriarchal societies have to go through is being told what they can and cannot do. But not long after Zahra Nader was told she would not make it as a top reporter, she joined The New York Times, the first woman from Afghanistan to report with a major English-language news outlet. Later she founded her own media site, the Zan Times, to bring the stories of women from the areas where they are most suppressed. As she said: “Because we are able to carry the meaning.”

Soft Skills are Valuable Too

Panelists pointed out that women reporters shouldn’t be feel constrained by expectations of what skill sets a “typical” investigative journalist should have. So-called soft skills have value too. “Those are the ones that allow us to connect and have helped advance collaborations,” Díaz-Struck noted, citing as examples women editors and managers who have been behind leading international investigative projects. Chua agreed. “Women have a different way of communicating, bonding, and helping each other,” she said. “Don’t ever lose that — it’s one of the most valuable things we have.”