Investigative Journalism & Foreign Aid: A Huge Return on Investment

The Vimpelcom Case: One exposé, and $800 million.

It is a windfall of epic proportions. In February, Russian/Norwegian telecom giant Vimpelcom announced it will pay US$795 million to settle charges of foreign bribery, an amount to be split equally between the Dutch and American governments. As part of the settlement, Vimpelcom will admit to paying off the government of Uzbekistan to operate in that country’s lucrative mobile phone market, a violation of the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Dutch anti-corruption laws. The profits were apparently enough to justify more than US$100 million in bribes by the company.

Vimpelcom’s base in Amsterdam and use of the U.S. financial system gave prosecutors the grounds to go after the company, the world’s sixth biggest telecommunications firm. It is believed to be the largest settlement by prosecutors in the history of the Netherlands, and one of the largest cases ever charged under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

And yet, despite the case’s high profile and big payoff, prosecutors in those countries had no idea about the bribes until they were exposed by a team of journalists in March of last year. They were alerted to the case through an exposé by investigative reporters working for Swedish Television (SVT), Sweden’s TT News Service, Norway’s Klassencampen newspaper, and the nonprofit Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

It’s not unusual for investigative reporting to lead to huge fines. The Guardian’s reporting on bribes by defense contractor BAE Systems eventually led to over US$440 million in penalties paid to the U.S. and UK governments. A series exposing hidden offshore wealth by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists resulted in vast sums in fines and back taxes recovered by officials worldwide. South Korea alone has ordered 11 people named in the ICIJ series to pay $65 million. OCCRP calculates that its reporting over the past six years has led to over $2.8 billion in fines and seizures, with officials actively trying to seize another $1 billion.

ICIJ’s Offshore Secrets sparked a global crackdown on tax evasion, with millions of dollars recovered by governments worldwide.

What is shocking about these numbers is how they compare to the paucity of support to investigative reporting by institutional and government donors.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the development of an independent press has become an important, if poorly funded, element of international assistance by Western nations to developing and transitioning countries. USAID and the State Department, the EU and member states, UN agencies like UNESCO, the World Bank, and private funds like the Ford and Open Society foundations all agree that building independent media is as essential to development as good industrial policy, rule of law, and educational reform. Investigative journalism has won a small but important corner of that funding; modest sums over the years have helped train thousands of journalists, kick-start investigative teams and nonprofit reporting centers, and inspire exposés of kleptocracies, human rights abuses, and environmental nightmares. It’s helped establish a tradition of in-depth and accurate reporting in countries saddled with corrupt governments and no history of independent journalism.

“Investigative journalism is absolutely essential,” observes Nobel Prize-winning development economist Joseph Stiglitz. “Poor people in developing countries have few options. That makes them particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Investigative reporting plays a very important role in making sure when that kind of exploitation occurs it’s uncovered.”

A watchdog news media pays other dividends that are not easy to quantify, such as acting as a brake on exploitative and criminal behavior. “The very fact that there are investigative reporters out there discourages this kind of activity from occurring,” Stiglitz adds. “So it actually acts as a deterrent.”

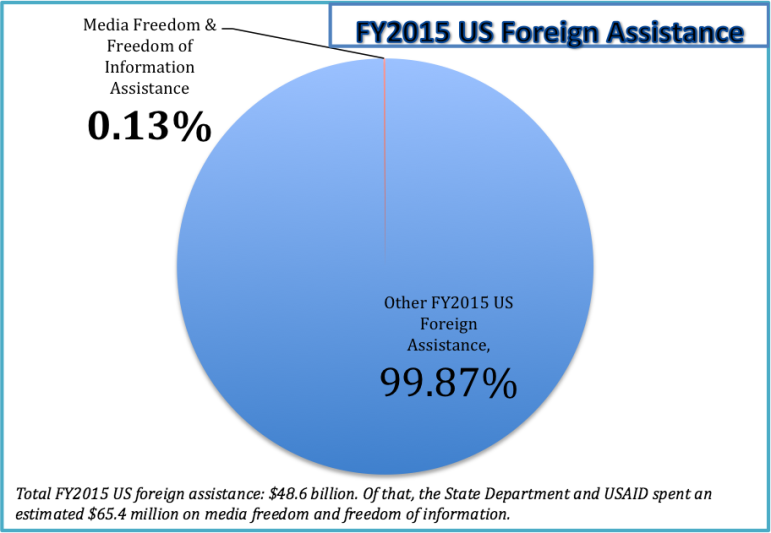

Despite all this, media development accounts only for a fraction of development funding. In FY2015, the U.S. State Department and USAID spent an estimated $65.4 million on media freedom and freedom of information — about 0.1 percent of total U.S. foreign assistance that year.

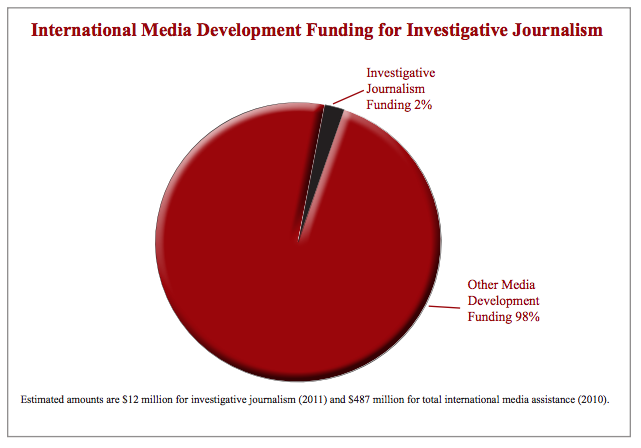

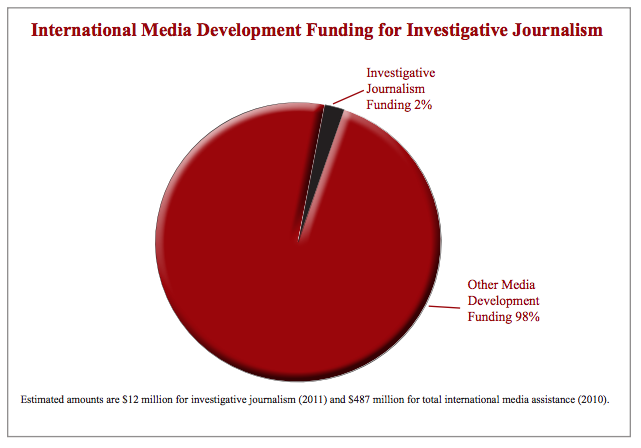

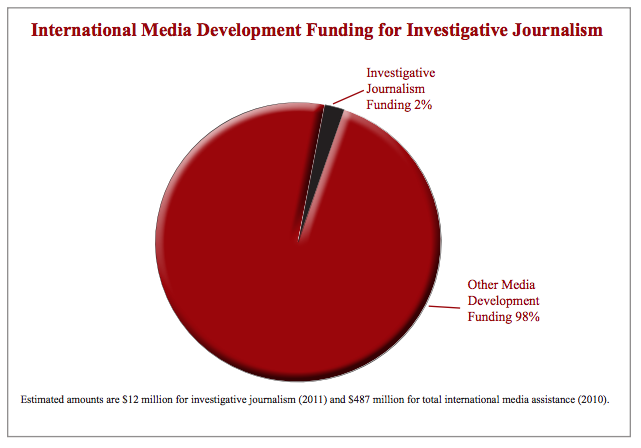

And of that 0.1 percent, investigative journalism programs accounted for a few million dollars — a fraction of a fraction. Worldwide assistance from all countries to investigative journalism programs in developing and transitioning countries amounted to just $12 million in 2011 – about 2.4% of global media assistance aid, according to a survey by the Center for International Media Assistance. The paltry amounts going to watchdog reporting were confirmed by CIMA in a second study a year later. “The lack of investigative projects announced by USAID and the State Department was certainly notable, and was similarly meager year after year,” the report found. Little has changed since the CIMA studies.

Source: Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support, Center for International Media Assistance, 2012.

What about all the other money that goes to media development? Bear in mind we’re not talking here about open government initiatives and handy tech apps to help with security and gathering the news. Nor are we talking about workshops on how to cover elections or health issues. These are welcome developments, but they do not take the place of in-depth, on-the-ground investigators who know how to develop human sources, follow secret trails, and uncover massive corruption and abuse of power. As the movie Spotlight so well depicts, to expose major abuses by powerful institutions the world needs investigative journalists.

Perhaps putting it in business terms might help. Let’s use OCCRP as an example. Based in Sarajevo, OCCRP is a media development organization that does investigative projects in the post-Communist countries of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Over the years it has accepted $5 million in funding from the U.S. and other governments. The return on that funding? With $2.8 billion recovered in fines and seized assets by various governments, the payoff is over 56,000 percent (or a 560-fold return). In the business community, success at that level evokes names like Google and Facebook. OCCRP could fund itself almost permanently on the interest of just one percent of the money governments have made from its work. Instead, like investigative journalism groups in so much of the world, OCCRP must scramble for funds to survive another year.

If investigative journalism is so profitable for governments, why aren’t they supporting more of it? That may be because media development is often designed and implemented by donors and implementers who don’t understand investigative journalism or how to improve it. So instead of promoting more complex but high-impact investigative reporting, most development money is spent on more mundane training and projects.

Or maybe we just haven’t made a convincing enough case yet.

Given the vast windfalls from investigative journalism, perhaps a portion should be earmarked to ensure the field receives adequate support. Governments could take a percentage of what they gain from the work of journalists and set up a trust to help ensure this invaluable profession stays in business and continues to spread around the world.

Such an approach is not without potential problems. In many countries, the United States among them, investigative reporting organizations steer clear of direct government subsidies, to avoid conflicts of interest and official interference. In poorer countries and in Europe where government money in media is more common, organizations may more readily accept government subsidies, but they will still need firewalls guaranteeing independence.

There is a precedent for such a mechanism: under the U.S. False Claims Act, private citizens blowing the whistle on fraud and other criminal acts can earn between 15% and 25% of any proceeds the government recovers. Over the years, whistleblowers, private investigators, and lawyers have made billions of dollars through these so-called “qui tam” cases.

We are not suggesting that journalists act as whistle-blowers or bounty hunters. This might incentivize reporters to focus on stories or issues that might lead to fines. You don’t want investigative reporters setting bounties on the head of wealthy but morally corrupt industries, however desirable that may sound at first glance. Nor would the law likely allow it; Under the False Claims Act, journalists apparently cannot make claims for their work.

Instead, we believe that our colleagues would applaud seeing a portion of the recovered funds put into an independent trust fund to support investigative journalism in the most embattled spots of the world. Given the dramatic impact that such reporting has had around the globe, and the small investment from what has become a rather large pie, this seems an idea worth considering.

In the end, we need investigative reporting and we need to pay for it. Perhaps it’s time we looked beyond the current broken system and recognize that we need to invest in strengthening a global watchdog news media.

David E. Kaplan is executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, an association of 128 groups in 58 countries working to support investigative reporting. He has served as director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and as chief investigative correspondent for U.S. News & World Report.

is executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, an association of 128 groups in 58 countries working to support investigative reporting. He has served as director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and as chief investigative correspondent for U.S. News & World Report.

Drew Sullivan is a veteran journalist and media development specialist with a decade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. He founded the Center for Investigative Reporting in Bosnia-Herzegovina and served as its director. He is co-founder and editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a regional consortium of investigative centers.

is a veteran journalist and media development specialist with a decade in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. He founded the Center for Investigative Reporting in Bosnia-Herzegovina and served as its director. He is co-founder and editor of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a regional consortium of investigative centers.