Indonesia’s Tempo Leads Asia into Cross-Border Collaborations

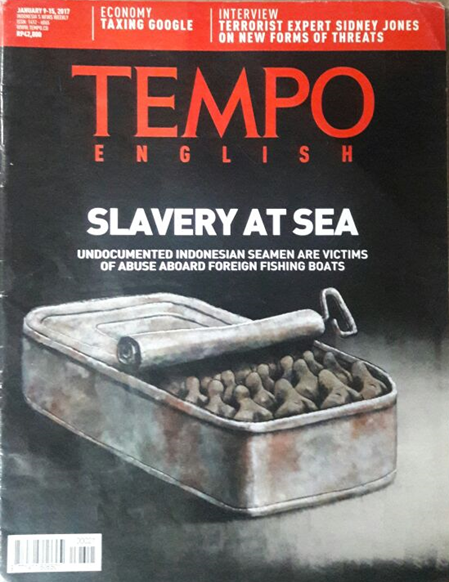

Newsrooms in Asia have traditionally worked alone, guarding their sources and tip-offs fiercely and keeping their stories and investigations in-house. But after attending GIJN’s Asian Investigative Journalism Conferences and participating in the global Panama Papers investigation, Indonesia’s top newsweekly Tempo has been inspired to reach out to Asian colleagues on cross-border collaborations. Last year, Tempo worked with The Reporter from Taiwan to expose slavery of Indonesians aboard Taiwanese fishing ships and this year, they collaborated with Malaysiakini to expose human trafficking networks of Indonesians through Malaysia.

Newsrooms in Asia have traditionally worked alone, guarding their sources and tip-offs fiercely and keeping their stories and investigations in-house. But after attending GIJN’s Asian Investigative Journalism Conferences and participating in the global Panama Papers investigation, Indonesia’s top newsweekly Tempo has been inspired to reach out to Asian colleagues on cross-border collaborations. Last year, Tempo worked with The Reporter from Taiwan to expose slavery of Indonesians aboard Taiwanese fishing ships and this year, they collaborated with Malaysiakini to expose human trafficking networks of Indonesians through Malaysia.

GIJN’s Eunice Au asked Tempo’s Managing Editor Wahyu Dhyatmika about forging a new era in Asian investigative journalism:

Is Tempo new to cross-border collaborations? How did these collaborations come about?

These two stories are our first ever cross-border collaboration for investigative stories. The Taiwanese story came about when Sherry Lee, the editor for Taiwanese digital investigative platform The Reporter approached me during GIJN’s Uncovering Asia Conference in Kathmandu, Nepal, last November 2016. She said she had a story that she believed is best pursued by an Indonesian media working side by side with a Taiwanese media. I was interested but wanted to see the initial documents and findings before deciding anything.

A couple of weeks later, her team arrived in our office in Jakarta. They brought documents, videos, testimonies about slavery on Taiwanese fishing vessels and about how Indonesian migrant workers working on board of those vessels are often the victims. We immediately agreed to collaborate on this story.

With Malaysiakini, it was us who came up with the initial story. We found some money transfers from Malaysian companies to people who were arrested in Indonesia as human traffickers. We wanted to track these Malaysians and expose their wrongdoings. I then contacted Aidila Razak, one of the investigative assistant editors in Malaysiakini whom I know because we both worked on the Panama Papers project. She instantly saw the significance of this story and agreed to work together.

Why did Tempo choose to pursue these stories through collaborations instead of going it alone?

For several reasons. First, obviously media and newsrooms understand their home turf better than anyone else. If we want to do a story involving the Taiwanese fishing industry, the best option is to find a local partner in Taiwan, and vice versa, if you want to do a story involving something that happened in Indonesia, then it is better to have an Indonesian newsroom to collaborate with.

Secondly, budget-wise it is much more efficient. You don’t have to send a team of reporters to another country; that might cost your newsroom a lot of money which will never get approved by the finance team anyway. By collaborating, you have an extra team in another country, as long as you provide yourself to become the extra team your partner needs in your own country.

Secondly, budget-wise it is much more efficient. You don’t have to send a team of reporters to another country; that might cost your newsroom a lot of money which will never get approved by the finance team anyway. By collaborating, you have an extra team in another country, as long as you provide yourself to become the extra team your partner needs in your own country.

And third, impact. Collaborative stories get noticed sooner by the authorities, because you publish the same story via prominent outlets in places where it matters the most. Our story about human traffickers in Malaysia will not get attention in Malaysia, but since the story is also published by a prominent media in Malaysia, the government has to respond. A Taiwanese story about slavery will not get attention in Indonesia, but once we published it here, it became a huge story.

How has working with other newsrooms helped better inform and strengthen Tempo’s reporting?

With our colleagues at The Reporter in Taiwan, we shared all our findings with no exceptions. The whole project would not have happened without their role in getting the first crucial documents about the alleged crime. We also obtained important comments from Taiwanese authorities, thanks to them.

With Malaysiakini, we teamed up in tracking the traffickers in Malaysia. We sent one reporter to Kuala Lumpur to work side by side with the Malaysian investigative team. It wouldn’t go too far in collecting critical information by sending a reporter abroad for several days if you did not have a collaboration. Working with Malaysiakini, we were able to tap into their deep and vast networks, knowledge, and expertise on the issue. That’s the real value in this kind of collaborative project.

What were the challenges you faced working across borders and how did you resolve them?

Communication is the key. If you don’t communicate then the whole project is in disarray. You will start wondering what is happening on the other side, whether they have met with any problems they can’t resolve, or how much progress have they made in tracking and so on and so forth. So it is paramount to keep in touch at all times, whether you’re making progress or not.

It is also important to always remember that this is a joint project so everything needs to be decided together. You cannot make important decisions by yourself which will impact the whole project. Present the problem, talk it through, and decide together. With Malaysiakini, at one point, we needed to decide whether to send our reporters to confirm our allegations to the person accused, in a very unusual place and time. Malaysiakini and Tempo‘s editors then discussed the possible dangers, the exit strategy if the situation worsened, a back up plan, and all the things usually discussed only by top editors in our own newsroom. We listened to each other’s concerns and made sure everyone is on board with the final decision.

Were there any special communication platforms used to liaise the projects?

We created a Whatsapp group because it is the most commonly used chat platform both in Indonesia and Malaysia. And because we’re not too far apart, only two hours by plane, it was easy to set up a face-to-face meeting. With Taiwan, we set up Skype chats and used Facebook messenger and emails.

We created a Whatsapp group because it is the most commonly used chat platform both in Indonesia and Malaysia. And because we’re not too far apart, only two hours by plane, it was easy to set up a face-to-face meeting. With Taiwan, we set up Skype chats and used Facebook messenger and emails.

Were there any extra security measures taken?

Since both stories involved human traffickers and were not targeting digitally sophisticated entities, we did not set up strict security protocols in our communication methods. Of course, it would be completely different if we’re dealing with financial institutions or government bodies.

How did Tempo organize the sharing of information, sources, and reporting tasks? Was anything off limits?

Tempo’s reportage on human slavery aboard Taiwanese fishing boats, done in collaboration with The Reporter.

There was nothing off limits. We radically shared everything: sources, findings, documents, etc. If a source only talked to us, then we shared the interview but our partner needed to mention specifically that the interview was conducted by Tempo. From the beginning, we agreed on only two basic rules: share everything and publish together, just like in Panama Papers. When we collaborated with The Reporter, we also sent one reporter to Taiwan to dig for our own story angle and do the reporting together with their team. They also sent a team to Indonesia. We sent a reporter to Malaysia for the same reason.

The collaboration with Malaysiakini involved setting up an interactive map. What software was used and how was the project managed?

It was built using StoryMapJS by Malaysiakini‘s team, but most of the content (the text, photos, documents) were provided by Tempo. Malaysiakini took the lead and full responsibility in making sure the visualization was completed on time.

It was built using StoryMapJS by Malaysiakini‘s team, but most of the content (the text, photos, documents) were provided by Tempo. Malaysiakini took the lead and full responsibility in making sure the visualization was completed on time.

Groups like ICIJ and OCCRP have been successful at coordinating global investigative projects. What is the future for these kind of collaborations in Asia?

I believe it is possible to coordinate big regional stories involving more than two countries in Asia. These two stories are only the beginning. We have regional organizations like the Southeast Asia Press Alliance (SEAPA) that have been around for decades and quite successful in organizing regional fellowships and other events. My organization, the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) and Malaysiakini are members of SEAPA. We only need to inject some investigative journalists as additional resources so SEAPA can start working on global investigative projects in Asia.

What would you say are the three most important ingredients in collaborative, cross-border investigations like these?

The most important ingredient is the story. The story has to be important and interesting enough for all the media involved. Getting that story and publishing it is the most important driving force behind a collaborative project. If one media views the story as not too important for their own audience then they will be reluctant to be involved and put in their resources.

Second and third ingredients are equally important and interlinked: trust and respect. We need to be able to trust our partner in this project. We cannot work together, let alone use materials gathered by our partner, if we didn’t believe that our partner upholds the same standards of verification and ethics as ours. However, we also need to keep in mind that our partner’s newsroom is not ours, we cannot boss them around, ask this or that as if they’re working for us. We need to respect each other’s boundaries and decision-making process. At the end of the day, we have to remember that it is a joint project, so all parties involved have to show the same level of willingness to work together and employ all resources needed to get the story.

Tempo was part of ICIJ’s Panama Papers team and its editors have been active participants in GIJN’s first two Asian Investigative Journalism Conferences. How important were those in inspiring these projects?

It is fair to say that these projects wouldn’t even exist without GIJN’s conferences and our partnership with ICIJ. Those conferences provide us with possible networks, story ideas, and inspiring ways to manage stories and teams. And Panama Papers proves that it is possible to collaborate across borders for investigative stories.

Wahyu Dhyatmika is a managing editor at Tempo Newsroom. He is also a board member of the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia. He was previously managing editor of Tempo’s Investigative Desk where he was involved in both in-country and cross-border investigations like SwissLeaks and the Panama Papers. He was a Nieman fellow at Harvard in 2014-15.

Wahyu Dhyatmika is a managing editor at Tempo Newsroom. He is also a board member of the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia. He was previously managing editor of Tempo’s Investigative Desk where he was involved in both in-country and cross-border investigations like SwissLeaks and the Panama Papers. He was a Nieman fellow at Harvard in 2014-15.