How We Proved That the Biggest Black Lives Matter Page on Facebook Was Fake

In the summer and fall of 2017, as the world began learning the details of Russia’s expansive effort to influence American voters through social media, it became clear that African Americans and the Black Lives Matter movement were among the main targets of the Kremlin’s campaign to sow division.

My colleagues at CNN and I spent months reporting how Russia had been behind some of the biggest Black Lives Matter (BLM) accounts on social media. As I spoke to BLM activists, I would sometimes be asked, “Do you know who runs the biggest Black Lives Matter page on Facebook?”

Incredibly, no one — including the most prominent BLM activists in the country and organizers on the ground — knew the answer. Some had understandably suspected the page might be run from Russia. But our investigation found it wasn’t Russian, or American — it was run by a white man in Australia.

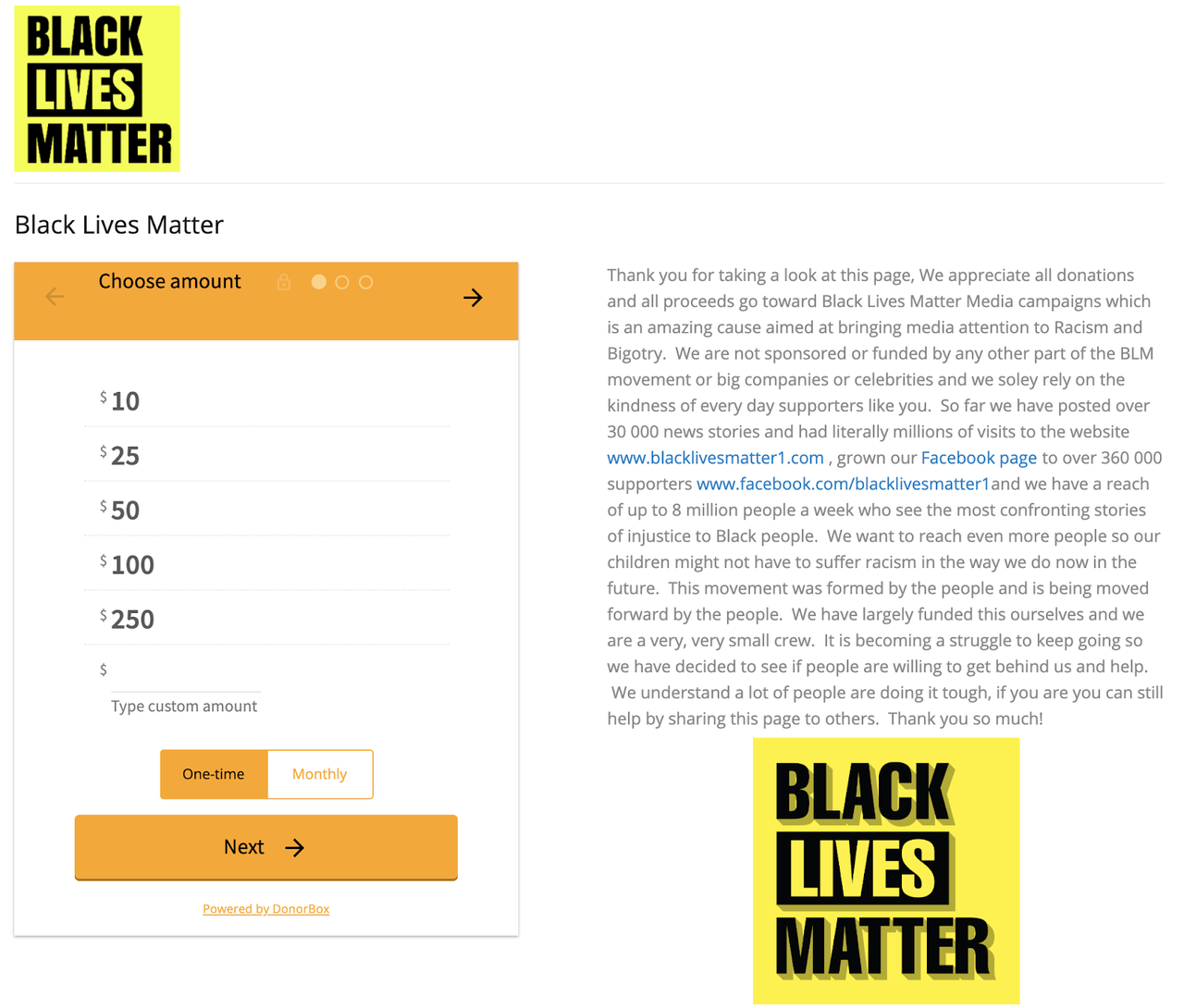

The page, simply titled Black Lives Matter, looked legitimate. As of April 2018, it had almost 700,000 followers. It consistently shared links to stories about police brutality and inequality; it ran online fundraisers; it even had an online store that sold BLM merchandise.

It’s not unusual for a page that size to be run anonymously. Some activists don’t want to put their names on a page and risk attracting attention from trolls or scrutiny from law enforcement looking to shut down protests. Outside the United States, the ability for activists to run pages anonymously has been critical to digital activism and key to some movements. (It was also precisely what Russia exploited, adding to suspicions that this BLM was connected.)

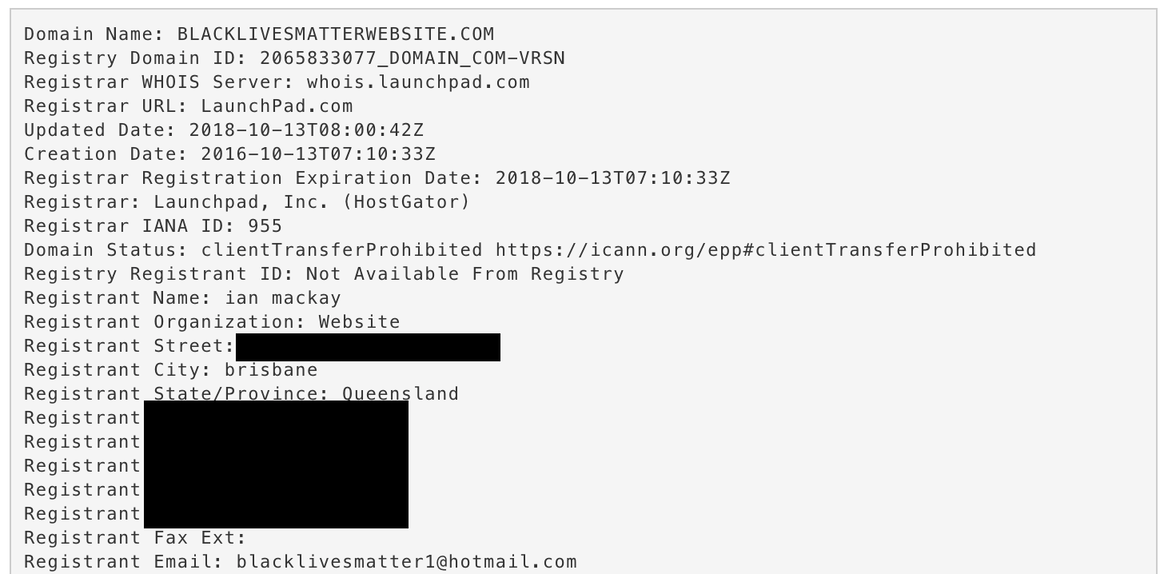

Around the time I began paying attention to this mysterious page, Jeremy Massler, a freelance investigator and incredible online sleuth, reached out with a tip. Massler had looked at the domain registration records of websites that the huge BLM Facebook page was consistently linking to. Although the domains had been registered privately, he found one of them had, for a period in 2016, belonged to a person in Australia, named Ian MacKay, a white man.

Massler contacted MacKay, who told him he bought and sold domains as a hobby and had nothing to do with the Facebook page. It was the same excuse MacKay, a middle-aged union official, gave me when I reached him by phone a few months later. But by that time we’d found that MacKay had registered dozens of website names, many relating to Black activism.

Despite my concerns about the page and the fact that several activists told me they were suspicious of it, I didn’t find MacKay’s explanation unbelievable on its face. Domain names can be valuable, and people buy and sell them all the time. The fact he had also registered and sold domains that were not related to Black activism made his case even more credible. But then something strange happened. A few minutes after I spoke to MacKay, the Facebook page came down. It hadn’t been taken down by Facebook, but by whoever was running it — and it hadn’t been deleted, only temporarily removed.

That seemed suspicious, so Massler and I began to dig more. The Facebook page, which came back online in the weeks after my call with MacKay, had during its lifetime promoted fundraising campaigns ostensibly for BLM causes.

In one instance, it claimed to be raising money for activists in Memphis, Tennessee. But when I spoke to activists there, no one knew anything about the fundraiser or where the money might have gone. Other activists even told us that, suspecting it was a scam, they had reported the page to Facebook. But the company hadn’t taken any action.

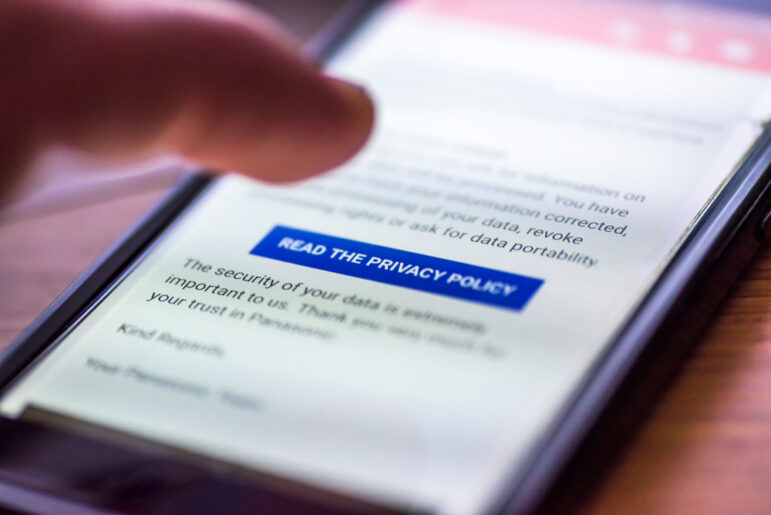

As I started to contact the multiple online payment and fundraising platforms the page had used, those companies began removing the fundraisers, saying they had broken their rules. Citing user privacy, none of the payment companies provided me with information on the record about where the money was going. This is a common challenge. Citing their privacy policies, platforms and digital services rarely reveal the names or contact information of account holders to the press.

I later learned from a source familiar with some of the payments processed that at least one account was tied to an Australian bank account and IP address. Another source told me that around $100,000 had been raised. Developing sources at tech companies who are willing to tell you more information than the company will say on the record is becoming increasingly important, as many stories cannot be uncovered purely using open source information as scammers and bad actors become more sophisticated.

I brought this information to Facebook to comment for the story and told them I had evidence the page was linked to Australia, that payment companies had removed the campaigns after they investigated, and that we knew some of the money was going to Australia. A Facebook spokesperson said the social media platform’s investigation “didn’t show anything that violated our Community Standards.”

It wasn’t until shortly before publishing our story — and only after I raised my concern about Facebook’s investigation and its spokesperson’s response to a more senior Facebook employee — that Facebook took action and removed the page.

The Australian workers’ union where MacKay worked launched an investigation of its own after CNN’s report. By the end of the week it had fired MacKay and a second official it said was also involved in the scam.

Using Online Tools to Solve the Riddle

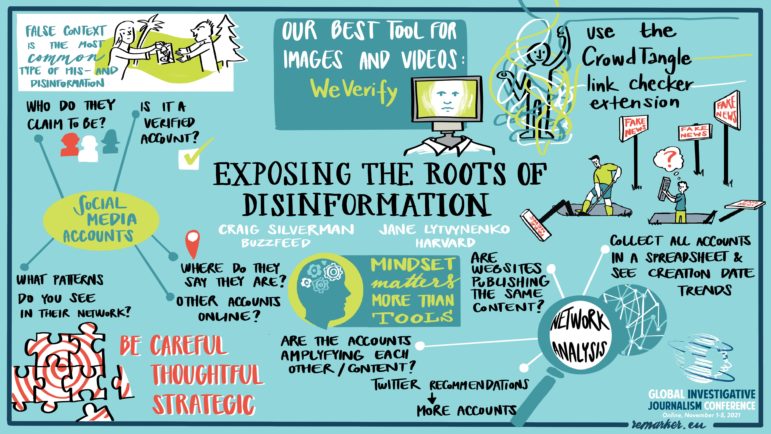

What was particularly notable about this story was the array of techniques that Massler and I used to get it over the line. We relied heavily on archive sites like the Wayback Machine that allowed us to see the look of websites the page had been linking to, and the page itself, before it came on our radar. This was particularly useful, as after Massler initially contacted MacKay, the people behind the page began trying to cover some of their tracks.

We also used services that track domain registrations, including DomainTools.com, to investigate the sites MacKay had registered and also to find his direct contact details. Massler also extensively used Facebook Graph Search (a tool no longer available) to track the fake Facebook profile accounts that had been set up to promote the page in Facebook Groups. Interrogation of open source information and use of online research tools, like those used to access domain records, are vital instruments, but they are not the only ones.

The simple act of picking up the phone to talk to MacKay, and developing sources to provide information that would otherwise not be made public — traditional journalism techniques — were critical in exposing this scam.

Further Reading

For more on fact checking and verification check out GIJN’s Resource Center, including this guide to resource tools to help journalists track people down online.

This story was originally published by Datajournalism.com. Here is the original post, which is republished with permission.

Donie O’Sullivan is a CNN reporter covering the intersection of technology and politics. He is part of the CNN Business team and works closely with CNN’s investigative unit tracking and identifying online disinformation campaigns targeting the American electorate.