How To Monitor Social Media for Misinformation

Read this article in

For journalists trying to keep an eye out for misleading claims and content on social networking sites, there are a stupefying number of channels to track and posts to read. But the value of monitoring at least some portion of this content is undeniable. Just consider the recent case in which CNN’s KFile was able to identify the original source of a Trump-CNN smackdown video tweeted by the President.

For journalists trying to keep an eye out for misleading claims and content on social networking sites, there are a stupefying number of channels to track and posts to read. But the value of monitoring at least some portion of this content is undeniable. Just consider the recent case in which CNN’s KFile was able to identify the original source of a Trump-CNN smackdown video tweeted by the President.

Thankfully, there are accessible tactics and tools out there to help make the task of monitoring social media more manageable. Before you can begin thinking usefully about how to monitor Facebook or Twitter, though, you have to figure out what you’re going to be monitoring — groups and/or topics. And what you choose will depend on the social platform you’re looking at.

Reddit, although still frequently ignored by journalists, is an invaluable source to follow. According to Alexa, it’s currently in the top ten of most popular website in the world and even more popular than Twitter. Misinformation that ends up circulating widely on Facebook and Twitter often appears on Reddit first. One classic example from 2013 is the theory that a missing Brown University student was a suspect in the Boston Marathon bombing.

The blue search bar at the top of the subreddit search page (top) and the subreddit suggestions given at the bottom of the general search page (bottom).

Reddit is made up of a collection of open forums called subreddits, whose subjects include everything from aardvarks to alt-right politics. To find subreddits, use the blue search bar at the top of the subreddit search page or use the general search page and look at the subreddit suggestions given at the bottom. Both search engines will look for your query throughout entire subreddits, though each will deliver a slightly different set of results.

The subreddits suggested at the bottom of the general search page, for instance, are listed given how many times they’ve mentioned your search terms. However, in either case, it’s easy to generate valuable results. Searching for a web domain like thecanary.co will return subreddits that referenced the site. Even a search like “Obama is terrible” will return meaningful results like r/Conservative and r/The_Donald.

Once you’ve found an interesting subreddit, you can search for its name to discover similar subreddits. Also, keep an eye out for new subreddits mentioned in comments.

4chan

4chan is its own beast. It’s ephemeral. It’s chaotic. It’s anonymous. It’s ugly. (Be warned: you’re going to see some disturbing stuff.) But it’s also a place where barrages of tweets have been inspired or initiated: 4chan was the first place where the #MacronLeaks documents were posted.

4chan is its own beast. It’s ephemeral. It’s chaotic. It’s anonymous. It’s ugly. (Be warned: you’re going to see some disturbing stuff.) But it’s also a place where barrages of tweets have been inspired or initiated: 4chan was the first place where the #MacronLeaks documents were posted.

In one sense, 4chan is more straightforward to monitor in that by only watching six boards — /b/, /pol/, /int/, /x/, /news/ and /bant/ — you can cast a wide net over relevant discussions on the platform. However, these boards move rapidly. Posts also disappear after they’ve been inactive for three days, so you’ll have to use a third-party archive like Archived.Moe to read older posts. Finally, to see all the comments for a thread, you’ll have to click a button or link out to another page. As such, passively monitoring 4chan is not possible without doing some programming.

All that said, you can make the hunt for noteworthy content a bit easier. Using the “Find” feature on your browser, highlight terms like “http,” “twitter,” “facebook,” “mail,” “youtube” and the hash symbol “#” to pinpoint conversations that have a life beyond 4chan. There’s also a search bar at the top of every board, but it’s limited to matching terms in original posts or posts that initiate threads. Be careful when navigating to unfamiliar domains. Google the domain beforehand to check if it’s safe; it’s easy to pick up malware. (Note: I’ll be writing about user scripts in a later post.)

There are two key ways to monitor Twitter activity: terms and lists.

There are two key ways to monitor Twitter activity: terms and lists.

Using terms to find tweets is a matter of figuring out which of them tend to be used in the relevant conversations. (I’m using “terms” broadly to refer to any string of characters, including domains, hashtags and usernames.) So, ask yourself a few questions:

- Do I know any websites that produce misleading content?

- Do I expect the tweets I’m looking for to include certain words or hashtags, like “snowflakes” or “#LockHerUp?

- Are there particular accounts that are likely to be mentioned in these tweets?

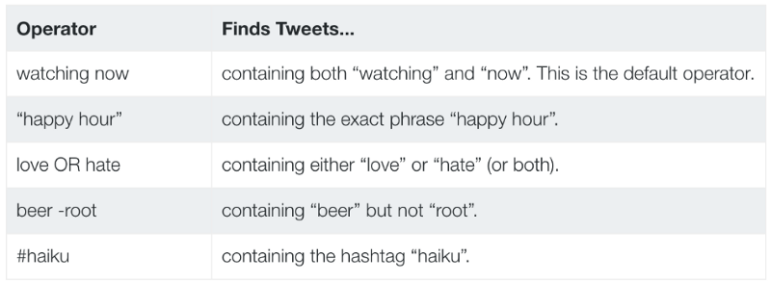

Go over Twitter’s Search API documentation to get a fuller sense of what you can do with your query. Encase discrete queries in parentheses and link them together with “OR.” If you start running into errors, split your query into parts.

Once you’ve formed a query, throw it into the Twitter search bar and take a look at what you get back. Notice any new terms that you hadn’t thought of and add them to your list. If you see a lot of irrelevant tweets that contain the same word, eliminate those results using the “-” operator. Repeat this process until you feel you’ve built a well-calibrated search query and save it somewhere on your computer. Conversations online are always changing, however, so it’s important to update your query regularly.

Apart from term-focused searching, lists are an effective way of quickly putting together groups of accounts to monitor. Lists are created by a user when they want to follow a group of accounts as a unit and are particularly handy because they let you capitalize on the expertise of other journalists. Use other people’s public Twitter lists to skip loads of work, but be sure to only use the lists of trusted sources. Nonsense lists abound on Twitter.

You’ll have to utilize a Google hack to search through lists on Twitter. (See this guide on Google search operators.) Add site:twitter.com/*/lists to the search bar. By doing so, you will delimit your search to sites whose URLs include the pattern following the colon. In this case, the pattern is that of a URL for a Twitter user’s lists, and the “*” is a universal placeholder for a username. Thus, by adding this term, you can search the public lists of all Twitter users — or more specifically the names of these lists. So think about how someone might name the lists you’d be interested in, trying different iterations of the same or similar terms.

In addition, look at what lists a user has created, or belongs to, by going to his or her profile, clicking “More” and then clicking “Lists.” As a last step, combine the lists you’ve found into super lists using Twitter List Copy. You may want to keep the lists you create private, if you don’t want others to know who you’re sleuthing. (More on Twitter lists here.)

The potential to monitor Facebook is narrower than other platforms. First, you can only see content that has been designated public by users. Second, Facebook does not support direct, programmatic access to the public feed — or the stream of all public statuses — for anyone other than a few publishers. This means there is no way to flexibly monitor statuses, and you’ll have to center your search on pages and groups.

The potential to monitor Facebook is narrower than other platforms. First, you can only see content that has been designated public by users. Second, Facebook does not support direct, programmatic access to the public feed — or the stream of all public statuses — for anyone other than a few publishers. This means there is no way to flexibly monitor statuses, and you’ll have to center your search on pages and groups.

Facebook’s search bar is limiting when searching for pages and groups because your search query is only matched with names. So if you’re unsure of what a relevant page or group might be called, this approach isn’t going to get you far. (Watch this video for more on searching Facebook.) Again, Google comes in handy here. Add site:facebook.com/pages or site:facebook.com/groups to your query to search within pages’ and groups’ descriptions in addition to their names. Also, adding “-places” to a pages query will remove all places, like restaurants, from your results.

You can focus on active pages by changing Google’s date settings: click “Tools” and then “Any time.” Technically, you can search for posts from pages or within public groups with Facebook’s vanilla search bar, but you’re going to have to scroll through a bunch of spam.

Concluding Notes

More and more of what First Draft is interested in tracking is coming in the form of images. Unfortunately, there aren’t yet any free, ready-to-use solutions for passively tracking images on social networking sites. Moreover, the coordination of things like Twitter campaigns increasingly happens on closed, invitation-only messaging platforms like Discord, and accessing these conversations just comes down to good, old-fashioned reporting.

This post originally appeared on First Draft and is cross-posted here with permission. First Draft is dedicated to improving skills and standards in the reporting and sharing of information that emerges online, and offers free verification resources at firstdraftnews.com.

This post originally appeared on First Draft and is cross-posted here with permission. First Draft is dedicated to improving skills and standards in the reporting and sharing of information that emerges online, and offers free verification resources at firstdraftnews.com.

Nic Dias is a computational journalist and a senior research fellow for First Draft. A recent graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism, he has worked on First Draft’s UK Election project and written on digital astroturfing.

Nic Dias is a computational journalist and a senior research fellow for First Draft. A recent graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism, he has worked on First Draft’s UK Election project and written on digital astroturfing.