Jake Angeli, known as the "QAnon Shaman," at the US Capitol riots on January 6. Image: Shutterstock / Johnny Silvercloud

How Open Source Experts Identified the US Capitol Rioters

Read this article in

At 2 p.m. on Wednesday, January 6, journalists at investigative nonprofit Bellingcat began sharing urgent messages — like “let’s start pulling video now” — on their Slack channel as they saw TV images of rioters and Trump supporters breaching the US Capitol building.

At his home in Toronto, senior investigator Giancarlo Fiorella entered key words and protest event Twitter lists into TweetDeck on one computer screen, and divided two other screens on his desk for TV news and social media livestreams. Meanwhile, half a dozen research colleagues elsewhere, like Charlotte Godart, Aric Toler, and Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins, began their own, separate searches in Facebook, Instagram, and other platforms for posts and videos from the scene. Fiorella says they were also able to follow and grab portions of livestreams inside the Capitol, including some by the white nationalist activist known as “Baked Alaska,” who was streaming on an app called Dlive.tv.

They had to act fast, because they knew the rioters recording and sharing images of the violent insurrection would soon realize they were involved with serious crimes, and would begin deleting those clips. Directed to the Capitol by President Donald Trump, the violence surrounding the storming of the building ended in the death of five people and the injury of dozens of police officers, and ransacked America’s national legislature as it confirmed the election of Joseph Biden.

Beyond Bellingcat, an army of online sleuths sprang into action in response to the US Capitol assault. Open source experts at Toronto-based Citizen Lab and Czech data archive Intelligence X also rapidly archived materials — some using automated social media scraping programs. Perhaps the largest tranche was uploaded via the Reddit platform to the New Zealand-based cloud storage service, MEGA.

The collective result is that a massive trove of evidence has been preserved, helping to identify perpetrators and victims, understand the historic tragedy, assist law enforcement, and smash false counter-narratives — such as the effort by right-wing media to recast the event as a provocation by leftist infiltrators.

As they built their archives, these citizen investigators turned to an array of tools to identify and research the backgrounds of the rioters. At the forefront of the mob, it turns out, was a rogue’s gallery of far-right activists, white supremacists, and hardcore Trump loyalists, including a disconcerting number with military and law enforcement backgrounds. To track them down, investigators dug into social media, video clips, news accounts, and databases on far-right symbols. Some researchers, along with the FBI, turned to facial recognition software.

Bellingcat, a GIJN member, was well-positioned to dig into the riot. Based in the Netherlands but with a global network of open-source investigators, the group has won international acclaim for breaking hard-to-crack stories. Among them: the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 by a Russian missile, chemical weapons attacks against civilians in Syria, and the poisoning of Russian dissidents — most recently of leading opposition figure Alexey Navalny.

On the evening of the melee in Washington, DC, Bellingcat’s Fiorella saw an image of “the zip ties guy” — a rioter seen with white plastic handcuffs in a legislative chamber — vanish beneath the cursor on his computer screen, as the man’s Facebook account was suddenly deleted. But the researcher had already bagged plenty of other data from that page.

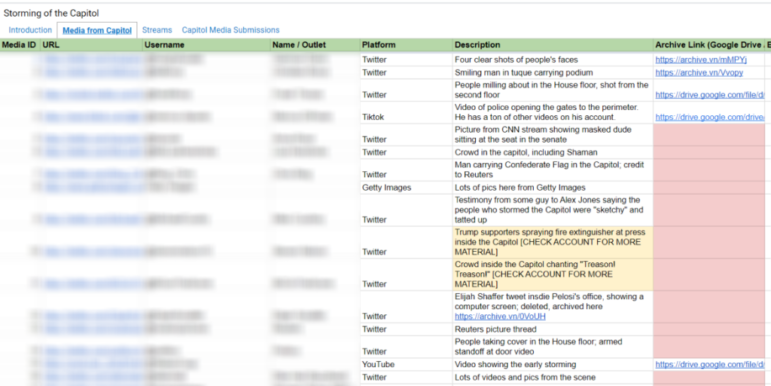

So the Bellingcat team created an Excel spreadsheet, where they eventually placed links to 260 confirmed on-scene “items” — some featuring dozens of images each — and used open source tools like Twitter Video Downloader to archive the videos. They have an additional backlog of 250 files that are yet to be checked. The keyword “Capitol” was so prevalent in posts, Fiorella says, that he didn’t even bother with geolocation searches in TweetDeck, though he says other investigators likely did use this code to narrow searches to the area.

These are just 18 of the hundreds of social media video clips from the Capitol that the Bellingcat team was able to scrape and archive in its spreadsheet.

The team also put out a crowdsourcing call for citizens to send images of the chaos directly into their submissions folder, and created an online form for verification.

“I’ve been at Bellingcat for two years, and this event has received the biggest reaction I’ve seen, in terms of engagement; of ordinary people submitting material and saying ‘How can I help?’” says Fiorella. “Yes, there is Python script and there are facial recognition tools that are advanced, but if you just know how to copy links — Control-C and Control-V – and can think creatively about the words people are likely to use when news happens around them, then you can do this kind of work, or help.”

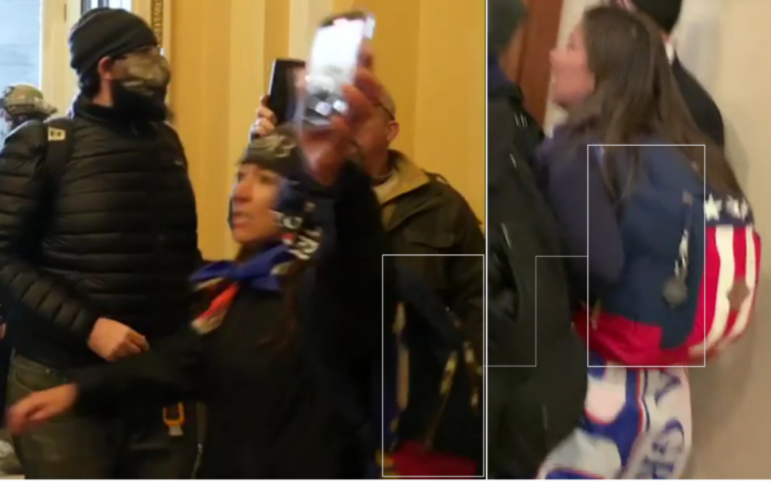

Within days, the Bellingcat team published a detailed account of how the allegiance of one woman — Air Force veteran Ashli Babbitt — had somehow moved from supporting the Democratic former President Barack Obama and then Donald Trump, to attending a violent insurrection at the Capitol, where she was shot and killed.

Bellingcat investigators used identifying features, and ITV News footage, to follow Ashli Babbitt’s movements within the US Capitol.

Bertram Hill, an open source sleuth with BBC Africa Eye, says the rapid scraping and archiving model used by Bellingcat on the riot — with every team member assigned to a different platform — had already proved effective in investigating violent public events in Africa. Hill has developed a dashboard of 200 open source and forensic tools for African investigative reporters, in particular, to use.

But Hill says planning, where possible, is still crucial.

“Ideally, you need an effective monitoring plan — to know beforehand which accounts are important when the event comes up, and which users will be at the event, even if they are the bad actors,” he explains. “I like to wipe the deck clean on TweetDeck, and input new columns based solely around that event, with key phrases, likely users, and relevant Twitter lists, so you don’t miss anything.”

In interviews with GIJN, Fiorella and Hill gave ten tips and techniques they use to document violent public events like the Capitol insurrection:

- Triage your downloads. Since people involved with riots are likely to be the first to delete their own social media posts, be sure to grab and archive videos and images as soon as possible. Of these, posts by those who appear directly responsible for criminal activity should be the very first to be preserved, according to Fiorella. This should be followed by material from innocent bystanders, and then videos posted on major platforms which could remove clips for violating hate and violence policies. Posts from journalists can potentially be downloaded later.

- Divide platform responsibilities as major events break. Fiorella focused on Twitter posts, using TweetDeck, while his colleagues mined Facebook and other platforms as events unfolded. Useful apps include Who Posted What?, which can mine Facebook using specific parameters. Bertram Hill says his team will often divide the tasks of monitoring Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, and WhatsApp between each member.

Bellingcat’s Excel spreadsheet of evidence from the riot is divided between vetted items — both those scraped by the team and sent in by contributors; livestreams; and submissions from the public.

- Consider free third-party sites to archive video — but code if you can. Consider platform-specific download sites — like twittervideodownloader.com for Twitter, FBdown.net for Facebook video, and y2mate.com for YouTube — and save the archived clips to your drive. Hill warns that downloads to third-party sites can potentially fall foul of platform rights policies, and that using basic coding skills for “command-line” software (where you type commands for text prompts) is a safer option. Hill suggests using youtube-dl for YouTube downloads; he stresses that learning the code script is relatively simple, using online tutorials.

- Look for original evidence from retweet reactions. “People just talking about a clip can lead you to evidence,” Fiorella explains. “Maybe the person who uploaded the video doesn’t say anything, but maybe someone watching the clip will say ‘Oh my God, I think in this video you can see the shooting!’” He says typed curse words are often associated with violent moments, so curses themselves can also be searched.

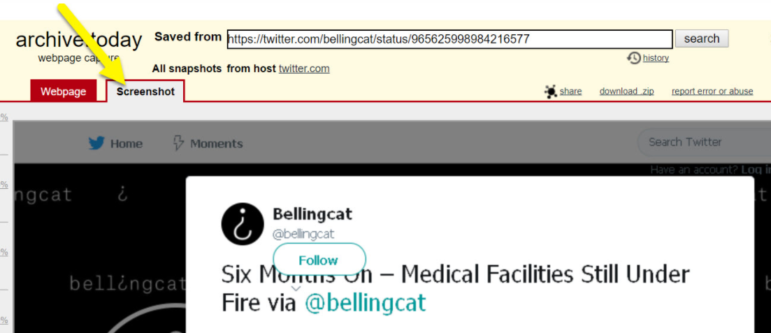

Although archive links are more secure, Bellingcat researchers point out that the screenshot function in the Archive.today tool can be useful in time-pressed moments; it can copy long social media pages as single images.

- Find a strategy for archiving livestreams that works for your team. Fiorella says archiving livestreams proved more complicated than other media during the Capitol siege. One team member experimented with an advanced extension tool, while Fiorella waited until the end of streams to grab the URL. Hill says standard screen-record functions “are notoriously tricky” but can sometimes suffice in capturing live video; more efficient, paid-for services can be purchased online. Hill also offers this important tip: “The great thing about livestreams is that they have metadata that can be really helpful.”

- Use Hunch.ly to archive your own search. Since some of the dozens of pages you visit during a rapid scrape effort could be deleted later — or become important later — use the Hunch.ly plugin to automatically record your digital steps.

- Secure text-based social media posts on reliable apps. Fiorella archived text posts from the Capitol on the Wayback Machine and Archive.today.

- Search reliable databases for identifying symbols. Fiorella says reliable symbol resources — such as the Anti-Defamation League’s Hate Symbols Database — can be useful in identifying far-right groups. “When we’re identifying tattoos, for instance, ADL is really useful, and, the other day, I was checking the ADL Hate Symbols Database to identify a flag,” says Fiorella. Even the typeface of slogans on flags and shirts can be checked on the WhatTheFont tool. For instance, recent research indicates that the “Cloister Black Light” font is most closely associated with militia groups.

Bellingcat scraped video clips like this one, posted to the right-wing website Infowars, to help identify rioters.

- Try a strong facial recognition app if all else fails. In addition to traditional reverse image tools like Yandex and the Google Images search, Fiorella says open source face recognition app PimEyes has proven useful for investigators in identifying individual rioters. “The site has some problems and there are huge privacy questions, but the technology is really incredible,” he says. “You just enter a screenshot of someone’s face, and PimEyes will search the internet for other pictures of that person. The clearer the original image the better.”

- Monitor parallel news and open source research in real-time. Building on what the news media and other researchers find is key, says Fiorella. “I learned the name of the zip ties guy because of an investigator called Regina Morales, who tweeted out a name, and ‘I think I got him.’ But someone should make a movie about the effort to identify this guy. John Scott-Railton (a senior researcher at Citizen Lab) was sort of coordinating the hunt, and he had honed in that this guy was from Tennessee, because of a symbol he noticed on the guy.”

Fiorella says the team was also working on a visual forensics story on the sustained assault on two police officers at the Capitol’s west side door, but left that project after seeing the “really excellent job” on that same event by the visual investigations team at The New York Times.

In addition to building a detailed timeline of events, from multiple camera angles, Fiorella said the Bellingcat team was building response plans and crowdsourcing resources for a possible second attack by far-right groups around the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden on January 20.

The FBI has warned of new protests by armed groups at all 50 US state capitals. Fiorella says Bellingcat’s experts are giving similar warnings: “There is open discussion now, about January 20. That ‘this time we’re going to win.'”

Additional Reading

The Forensic Methods Reporters Are Using to Reveal Attacks by Security Forces

Getting Started in Online, Open Source Investigations: Eliot Higgins

How to Use TweetDeck for Open Source Investigations

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.