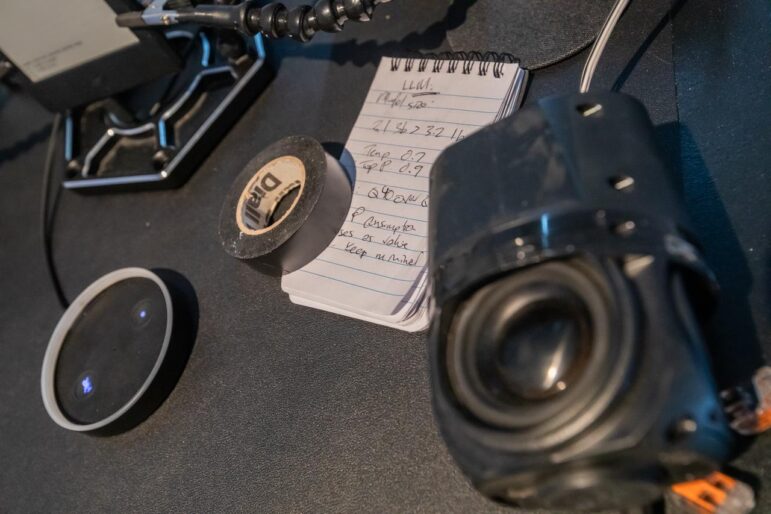

Careful preparation of clandestine reporting equipment is just one aspect to consider when going undercover as a journalist. Wesley Goatley & BRAID / The Horizon II / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

When to Go Undercover: Ethical Questions and Strategic Steps for the AI Age

Read this article in

Undercover journalism has produced some of the most unforgettable investigations of our time. It has helped free trafficked children, exposed corruption inside courts and prisons, and revealed the hidden machinery behind political manipulation.

Yet, as an undercover reporting session at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25) reminded the audience, this approach comes with a long list of ethical and practical dangers. Undercover work is never just an adventurous assignment — it is a moral minefield, the three speakers warned.

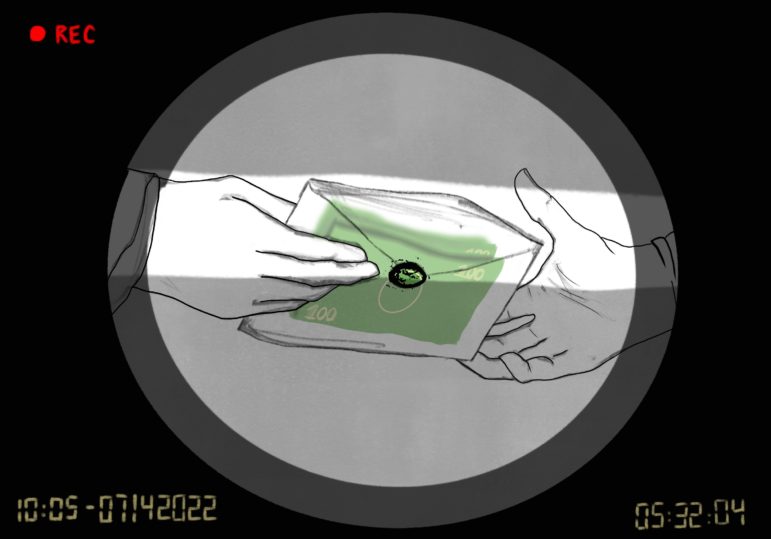

Anas Aremeyaw Anas, investigative reporter and founder of the Tiger Eye Foundation, opened the session with an overview of the types of investigations that have defined his career. In 2009, the Ghanaian undercover reporter infiltrated a psychiatric hospital by admitting himself as a patient. Sedated on arrival, he spent weeks inside the facility documenting abuse, neglect, and systemic corruption — evidence that led to the trial of multiple officials. In almost 20 years of undercover work, he’s exposed sex trafficking, corrupt judges, and football officials willing to throw entire matches for cash.

Choi Hye-jung, a journalist from Korean nonprofit investigative newsroom Newstapa, shared her experience going undercover when she was just an intern. Hye-jung infiltrated a far-right troll farm, Fingers for Freedom, which had flooded the country’s biggest news portals with comments. She exposed how the group manipulated online discourse, staged fake press conferences for politicians, and used bogus teaching certificates to enter schools and spread extremist narratives.

Daniel Adamson, editor and executive producer for BBC Eye Investigations, discussed a 2020 investigation in which his team sent an undercover reporter into a Kenyan public hospital posing as a woman trying to “buy” a child. They secretly filmed a doctor selling a baby for US$2,700 — evidence that led to the doctor receiving a 25-year prison sentence.

Adamson also described a 2025 investigation that infiltrated an Indian pharmaceutical factory producing illegal opioids for West Africa. Within two days of broadcasting the investigation, the team’s reporting led to police raids and new national regulations in India.

These stories make undercover reporting sound heroic — often it is — but, Adamson said, its far-reaching impact is precisely the reason not to use it lightly.

Ethical Questions: Should You Do This?

Before thinking about equipment or disguises, your team must answer three important ethical questions, the panelists agreed.

- Is the issue of undeniable public interest? Undercover work is justified only when exposure protects society. Exposing abuse, corruption, and systematic harm are credible reasons — mere sensationalist scandal is not.

- Is going undercover the only way? This is an essential question. For weeks, Choi’s team tried — and failed — to find whistleblowers before infiltrating the troll farm. Only when all open methods collapsed did they consider going undercover.

- Is there strong initial evidence of wrongdoing? Secret filming cannot be used to “go fishing.” Reporters must have concrete, documentable suspicions before entering a space or interaction under false pretenses.

“If any part of this test is answered with ‘no’, the project stops,” said Adamson. This rule is designed to prevent the slide from a public-interest investigation into tabloid journalism.

New Dilemma of the AI Era

Undercover reporters currently face a more modern threat — the digital trail. More than just a hidden camera, undercover work now requires cyber-literacy, encrypted devices, and a new kind of “mask” made of digital hygiene.

Hard questions must be asked, said Anas: “Do you strip the metadata and lose your credibility in court, or do you keep the metadata and expose your sources to danger?”

In the age of AI, metadata is forensic gold. It can help prove the authenticity of an image and pinpoint exact filming locations, devices used, and movement patterns.

This presents a conflict for investigative journalists: in the wrong hands, metadata can expose an undercover reporter or a source, but removing it will make images or footage less credible in court.

Pervasive surveillance is another threat. Modern CCTV systems can flag repeated visitors automatically, facial recognition can match even disguised reporters, and digital footprints can reveal who has joined which online communities.

Undercover work once relied on wigs and hidden cameras. Today “the mask is made of firewalls and encryption”, said Anas.

Preparing for the Dive

The GIJC25 speakers agreed that most of the “real” work happens long before the first hidden recording. They outlined five basic steps to consider during the preparation phase:

- Choose the right person: Choi was a perfect fit for the troll farm’s target demographic — a highly educated young woman with no public profile. Such alignment reduces suspicion and keeps reporters safe.

- Build a parallel digital identity: New email accounts, new social media profiles, and carefully curated digital behavior are now standard practice.

- Understand the legal limits: Every country has different laws on misrepresentation, recording, and access. Choi’s team avoided forging documents and used only real biographical details to stay within legal boundaries.

- Stress-test the equipment: Hidden cameras fail easily, batteries die, angles misalign — your team must test everything repeatedly.

- Have a rescue plan: Someone must always be nearby and ready to intervene. Undercover work is unpredictable; extraction plans save lives.

Staying Safe Inside

Once inside, reporters are observers — not participants. It is advisable to record as much as possible, even small details that may later prove crucial. Reporters should avoid steering targets into illegal acts.

When possible, real-time communication through encrypted channels helps teams analyze findings as they appear and can raise awareness of risky situations as they unfold.

Psychological Costs

The panelists were blunt about this: undercover work is emotionally brutal. Reporters face deception, danger, and sometimes traumatic scenes. Some journalists require therapy afterwards and others step back from journalism entirely. No newsroom should send someone undercover without support — before, during, and after — the speakers agreed.

Bottom Line: When to Go Undercover?

The panel suggested journalists should only go undercover if:

- The wrongdoing being investigated is serious and of clear public interest.

- Open reporting has been exhausted.

- Strong preliminary evidence exists.

- Risks to sources and reporters are manageable.

- Teams are prepared for AI-age surveillance.

- Legal and editorial oversight are in place.

- Psychological support is guaranteed.

Under these conditions, undercover reporting remains a vital tool that can reveal hidden crimes, disrupt harmful networks, and protect the public. But, if those conditions are not met, even the most dramatic undercover story simply isn’t worth the ethical and human cost.