Brazil’s Agência Pública: Where Journalists Innovate and Collaborate

Since March 2016, a pink two-story, 300-square-meter house on a tree-lined street in Botafogo, in the southern area of Rio de Janeiro, has been a haven and a venue for both Brazilian and foreign journalists and those interested in journalism and the ongoing changes surrounding the profession.

It is Casa Pública, the first cultural center for journalism in Brazil and a project of Agência Pública, a pioneering independent agency for investigative journalism. The house is also a temporary home for foreign reporters, an incubator for new storytelling ideas and an important space for discussion on the future of journalism in Brazil and Latin America.

Since its creation five years ago, GIJN-member Agência Pública has promoted a revolution not only in its country of origin, but around Latin America. It is one of the main drivers and representatives of a regional scene that brings together digital-native media founded and led by journalists that is becoming stronger and more relevant in the region.

Created and directed by journalists Marina Amaral and Natalia Viana, Pública was structured as a non-profit organization dedicated to investigative journalism and has been guided by the public interest and defense of human rights.

Starting with a Leak

The founders and current directors of Agência Pública met at the magazine Caros Amigos, where Amaral was a founder and editor and where Viana began as an intern in 2002, later becoming a reporter.

In 2006, Viana left Caros Amigos to pursue a master’s degree in radio journalism in London, where she became a non-profit investigative journalist through The Center for Investigative Journalism (CIJ). Upon returning to Brazil, she continued to report from various parts of the world, producing and publishing her investigations on human rights issues in Portuguese and English.

Through this international network of investigative journalists, Viana became the Brazil-based organizer of reports for Cablegate, a leak of US diplomatic cables released through WikiLeaks in early 2011. Though the two founders – as well as journalist Tatiana Merlino, who ended up leaving early in the project – had previously discussed the idea for Pública, Cablegate ended up being the site’s first big partnership and the impetus for its launch.

Muckrakers: Agência Pública’s founders Natalia Viana and Marina Amaral. Photo: Mary Kang/Knight Center.

“That’s when we founded Brazil’s first investigative journalism agency, mirrored a bit after the experience of ICIJ (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists), a little from what we learned with WikiLeaks, and also looking at what was happening internationally – the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the CIJ, ProPublica,” Viana explained to the Knight Center.

Amaral had started in journalism in 1984, working in some of Brazil’s largest newsrooms as a copywriter, reporter and editor. In 1997, she was part of the founding team at Caros Amigos, where she remained until 2007. She says that her experience at the print magazine, which closed in December 2017, gave her important elements for creating Pública.

“I’ve learned that to do such a business, you need money to lose,” Amaral recalled. “Since we did not have the money to lose, we thought, ‘Okay, let’s do what we know how to do: grind. Let’s get our work out there and from that work we will get resources.”

To make this project a reality and to sustain it, the directors and their team have experimented with different formats, reporting models and types of funding, while investing in the international distribution of their work and topics that are dear to them through exchange with foreign journalists.

Additionally, as part of their mission, they’ve incorporated an interesting strategy to disseminate their content, becoming “an agency and not an outlet,” as Amaral explained.

Media outlets can republish Pública’s stories under a Creative Commons license. As a result, 700 outlets republished Pública’s stories in 2017, according to Viana. “From super-influential sites like The Guardian (UK), El Páis (Spain), Folha de S Paulo, Valor Econômico and the blog Santarém in Pará (Brazil). It’s a very cool, very broad scope.”

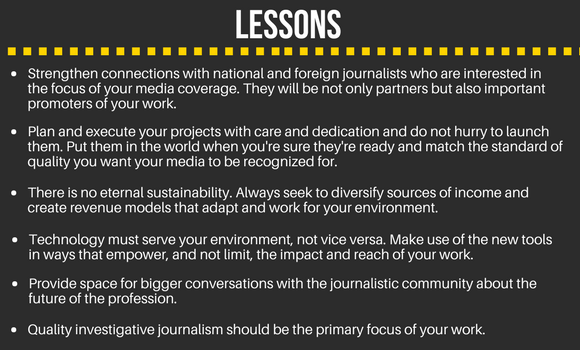

In the last seven years, the team’s diligence and the quality of the content produced by Pública have been recognized nationally and internationally by a few dozen prizes. Viana hinted at the key to the site’s success: “Nothing that we do is a result of a crazy idea we put in place overnight. Marina and I have a rule: if we do not feel it is firm, we wouldn’t put it out into the world. Let’s think about it a little more. We do everything very calmly, very carefully.”

A House to Celebrate Journalism

Viana shares an example of this level of care by highlighting one of the agency’s main projects: Casa Pública, the cultural center for journalism opened in 2016 in Rio de Janeiro after two years of planning.

Agência Pública was founded in São Paulo, where its headquarters and newsroom remain today. It’s where most of the team – currently 19 people – works under Amaral’s direct supervision.

But, it was in the city of Rio de Janeiro that the directors of Pública chose to set up their space to celebrate journalism, as described by Viana, who is responsible for the Casa and for the agency’s special projects. This choice was largely due to two major events hosted by the city in recent years: the 2014 Men’s World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics.

One of the goals of Casa Pública was to expand one of Pública’s mentoring programs, which it set up at the time of its founding. The Microscholarships for Reporting Contest provides freelance reporters with grants and guidance from the agency’s editors. They also wanted to invest in the incubation of other journalism initiatives led by journalists who don’t belong to any economic or traditional media group.

“We felt that it was worth expanding not only this work around incubation, but also the work of collaboration, conversations, events,” Viana said. “We thought of a project that would bring that side of collaboration and conversation around the Olympics, with a residence (for journalists). This was the initial project; Casa Pública would run during the year of the Olympics, it was designed for this. We knew there would be a lot of foreign journalists in Rio, so it was an opportunity to talk to them because Pública had covered human rights violations in relation to the World Cup and the Olympics since 2011.”

If at first Casa Pública served to revisit the agency’s investigations and connect foreign journalists with the larger context in which the Olympics were taking place, the space soon transcended its initial mission.

In addition to the Olympic Games, Brazil experienced another extraordinary moment in 2016: the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, then-president of the country. “People had nowhere to talk about it,” Viana commented. “There have been many conversations here that were very important. For example, we had a conversation that was really cool because it had everything to do with the house: foreign journalists’ views on the impeachment.” According to Viana, about 400 people lined up that day to enter the space, which comfortably fits 70 people.

“So, on the one hand, people needed a space to talk. On the other hand, students and people interested in journalism lacked a space to talk about the new journalism, a discussion that is not about the ‘crisis of journalism,’ the ‘end of journalism,’ bad wages, etc,” the director said.

It’s not about ignoring the problems, Viana explained. “But this is a space for us to experiment, reinvigorate and celebrate new journalism,” which she defines with several criteria: digital-native organizations, led by journalists whose primary purpose is to do journalism and who act with the goal of reaching long-term stability and sustainability. “These organizations are already changing Brazilian journalism and it will change even more very soon,” she believes.

In fact, it was from Casa Pública that the idea for Festival 3i came about. The event was held in November 2017 with the aim of promoting discussions on journalism that corresponded to three “I”s — innovative, inspiring and independent. In addition to Pública, independent digital media Nexo, Ponte, Agência Lupa, Brio, Nova Escola, Repórter Brasil and JOTA participated with the support of Google News Lab. Among the guests were representatives of independent outlets from other countries, such as Peru’s Ojo Público and Convoca, Argentina’s Chequeado and Tiempo Argentino, Guatemala’s Nómada and En Malos Pasos of Mexico, among others.

“From the beginning, we wanted to have an independent journalism festival,” Viana said. “The other day someone asked me, in the context of 3i, whether journalists in the traditional press can learn from us. Obviously they can, just as we can learn from them. But we learn from them all the time, because at every conference, at every conversation in a university, you listen to the perspectives of the traditional press, the traditional way of producing news. Cool, I do not think it has to go away, but I think there’s a lot going on that needs to be heard, and Casa also brings that.”

Journalism Residency

Casa Pública hosts more than conversations: journalists can also spend time on site as part of Pública’s residency program and LABs – its Journalistic Innovation Laboratories. The property holds up to eight people in two collective rooms on the second floor.

The residency program welcomes foreign journalists who can stay at the house for free for up to 15 days. During this period, they receive support from the Pública team in the production of reports on human rights issues in Brazil. Applications are submitted through Pública’s website.

The first round of residencies took place in 2016, at the time of Casa Pública’s opening, and focused on covering human rights violations in the context of the Olympic Games. At that time, Pública offered a scholarship for journalists who stayed in the house, and investigations were published in print and digital outlets from Chile, Ecuador, Kenya, the United States and Italy, among others.

“From Agência Pública’s point of view, it is cool because it not only strengthens exchange, relationships, contacts between journalists, but also increases the visibility of human rights issues in Brazil,” Viana said. “Covering this topic in Brazil is a rather inglorious task, and it is always helpful when something is published abroad.”

German journalist Caren Miesenberger was one of the two residents of the house this January. Based in Hamburg, she was selected for the program along with her story on the imprisonment of women in Brazil, to be published in feminist German magazine Missy Magazine.

“I learned about Pública in 2014 when I lived in Brazil for a year,” Miesenberger said. “I’ve followed its work ever since. I believe a lot in alternative, independent media, and what I admire most about Pública is the innovation aspect. This house is something very unique, I had never seen anything like it.”

She had already worked as a correspondent in Brazil investigating stories that were published in Germany, and she felt a difference between the two experiences. “A support network was missing. I would stay at my house, in front of the computer, writing the stories. There was no exchange. It’s the first time I’ve been in a place with a lot of journalists, and I feel very supported for my work, with exchanging ideas and suggestions for contacts.”

Miesenberger highlights the formation of ties between journalists from several countries as one of the most important points of the residency program. “There should be a house like this in all parts of the world so that we can form a network independent of the mainstream media and of interests other than good journalism,” she said.

Innovation Labs

Like the residency program, the Journalistic Innovation Laboratories (LABs) were conceived as part of the Casa Pública project and involve participants being immersed in the same space – the professionals carrying out projects who are from other cities stay and work in the house. In addition to the unique process for producing reports, the agency experiments with different formats and new technologies for its investigations in the LABs.

By January 2018, the results from five LABs had been published: “100,” which tells 100 stories of 100 families forcibly removed due to the Olympics; “Vigilância,” about how the security apparatus for the World Cup and the Olympics is used for repression and criminalization of demonstrations; “Museu do Ontem” (Museum of Yesterday), an application that traces the urban transformation of Rio de Janeiro’s port region, from the time of colonization to the Olympic Games; “Catraca” (Turnstile), on the ownership of bus companies in Rio de Janeiro; and “Coleção Particular” (Private Collection), on the illegal privatization of the coast and other public spaces in Brazil.

Private Collection: Screenshot of “Coleção Particular,” one of Pública’s Journalistic Innovation Laboratories stories.

Viana, the coordinator of LABs, has been responsible for inviting journalists and other professionals – designers, artists – who participate in the laboratories. Participating members have been members of the Pública team as well as freelancers who are chosen by Viana because of their experience with each theme, or for her trust in their contributions.

This was the case with Colombian Olga Lucía Lozano. A founder of digital independent site La Silla Vacía, Lozano served as creative editor for the first two LABs, which were launched in July 2016 and January 2017.

“I got to the first meeting with the local team and Natalia Viana said ‘Look, we want to tell 100 stories of 100 families that have been removed,’” Lozano recalled. The editor was responsible for finding solutions for this mission. “I started with how to gather 100 voices and tell 100 stories without losing the characteristic and individual tone of each one of them, but which can also really create an emotional bond with those who visit (the stories).”

Experimentation with the format was designed to facilitate the creation of this emotional bond, the editor said. “What I did was propose to create a small city in which you could find all the elements that are part of the 100, but to use them to tell the real stories: the door of a favela, of a person, a family,” she explained. The choice for audiovisual presentation, with interviews in video and audio and maps of the places where people were removed and where they were relocated, “allows us to see that people of flesh and blood” are living those situations, Lozano believes.

For Viana, the “Museu do Ontem” (the Museum of Yesterday), launched in June 2017, is the highlight of the LABs held so far. “Yesterday’s Museum generated a product that is very new. The previous LABs, Vigilância and 100, are very innovative interactive sites, but they are things that already existed before. The Museum of Yesterday is something else,” Viana said.

The application, created in collaboration with Dutch-Iranian developer Babak Fakhamzadeh, combines geolocation and investigative journalism to talk about the past and present of Rio de Janeiro’s port area. As users move through the area, new stories specific to their location are offered on their phones. From the desire to create an application that deals with the urban changes that took place in the city around the Olympics, the Pública team created a tool that tells stories of the occupation of the area – revamped as Porto Maravilha – over three centuries. It walks users from the colonial era of Brazil, when it was the main entry point of Africans enslaved by Europeans in the Americas, to the recent public works in the area investigated by Agência Pública, such as the disappearance of steel beams from the demolition of the Perimetral viaduct.

The last LAB, “Coleção Particular” (Private Collection), was published in December 2017, and there are two more LABs being produced. These will be published in the first half of 2018 and will close the first cycle of specials, provided for in the financing of Casa Pública. One will have three 360-degree mini-documentaries, Viana said. “We decided to explore this format, which is controversial. It was crazy, everyone was talking, and today people are more skeptical, but we thought it was worth it. LAB is to explore, and this is where we will be able to explore this format.”

At the end of the publication of the seven LABs which were planned as part of the original project, the idea is to evaluate what types of formats and technologies worked and to think about the future of the initiative. According to Viana, it is necessary to think about the real cost of the LABs, since the maintenance of platforms and tools – such as the Museum of Yesterday application or the collaborative map of the Private Collection special – was not accounted for in the original project. “Technology is a tricky business,” she said. “What you create, you need to maintain. The cost of maintaining an application is high. Higher than maintaining a website.”

Financing Innovation

The LABs and the residency program for foreign journalists are part of Casa Pública, which has its own funding because it is a project of Agência Pública. To launch the house in 2016, “we knocked on people’s doors, we received several no’s and some yes’s,” Viana recalled. The yeses came from organizations such as the Ford Foundation, Porticus, the Oak Foundation and the Open Society Foundations, providing funding for two years. For the next year, Ford, Oak and Open Society maintained their support.

“It’s a project, it has a deadline,” Viana said, adding that Pública is evaluating “if it’s worth it for the house to be permanent – we think it’s super important, we think it still has a lot more potential, but it’s expensive for the house itself, in Rio de Janeiro. We need to seek more funding for this project specifically.”

On its website’s Transparency page, Pública explains the sources and destinations of its revenue in 2017. The organization’s total revenue last year was about $840,000, raised from institutional funding, sponsorship and crowdfunding. In addition to Ford, Oak and the Open Society Foundations, the main funders are the Climate and Land Use Alliance and the Betty and Jacob Lafer Institute.

“At this point, what’s important for us is that we consolidate sources of funding for longer periods of time,” Amaral told the Knight Center at Pública’s office in São Paulo.

“Our priority is to make Pública a resilient organization that can have an eternal life, and that is not subject to this fragility of media outlets and organizations that live from foundations,” Amaral said. According to her, Pública follows the same model it had when it was founded: a non-profit organization, with funding from foundations or the public and without ads.

“Eternal sustainability does not exist,” according to Viana. Each year is a continual search for new revenue.

And so Pública has been innovating in that sense as well. Like Casa Pública, crowdfunding campaign Reportagem Públic (Public Report) and the Microscholarships for Reporting Contest are initiatives that diversify sources of revenue to finance the agency’s work.

Public Report is a collective funding campaign for reporting that Pública has carried out for three years: 2013, 2015 and 2016. The agency raised R$45,000 (Brazilian reals) (about US$14,000) in the first, while the last campaign raised R$85,000 (about US$26,000), R$5,000 more than Pública’s goal.

The model innovates by giving voice and vote to each person who donates to the reports. They help decide the stories that will be produced and have direct contact with reporters and editors about the outcome.

“Every month we send everyone who provided an email with three suggestions from three different reporters and ask them to vote,” Viana explained. “The winning story gets $7,000 and is produced, the other two are not carried out.”

In addition to the voting, contributors are invited to join a closed Facebook group where they can talk to the Pública staff, including journalists and editors who are producing the stories.

The Microscholarships for Reporting Competition calls for the participation of independent journalists who want to produce stories about the themes proposed in each edition. The reporters whose stories are selected by Pública receive R$7,000 (about US$2,100) and mentorship from the agency’s editors for two months.

The first two editions did not have a specific theme, Viana recalled. “From there we began to realize that there was a great demand from NGOs that were looking for Pública and said ‘Why don’t you do stories about Belo Monte?’ for example. We always respond that our financing policy is as follows: we do not do commissioned work. Pública only works on its own projects. Otherwise you’re going to trade the pressure of the advertiser for the pressure of the financier, and we do not want that.”

The themed minischolarships were therefore a way of combining the need for funding for the agency’s investigative journalism and the demand from organizations for investigation of certain topics. And very importantly, it ensures Pública’s editorial independence.

Among the microscholarship competitions that have already been held are ones on energy, sponsored by Greenpeace; children and water, sponsored by the Alana Institute; and marijuana, sponsored by the Center for Security and Citizenship Studies. The next, in partnership with Conectas Human Rights, will be about police violence, Viana said.

“The NGO gives us the theme, but they are broad themes,” Viana said. “Pública puts out the call for projects and receives the story proposals.” The site pre-selects some stories and then decides on the final selection along with the financier.

And this is the limit of the financer’s influence, she said. “Our partners rely on our work and do not see the material before it is published.” Pública then carries out the project coordination and editing.

“We have to think of ways to have different financing,” Viana said. “A lot of people are doing events, and crowdfunding is also super important. There are those who have subscribers, paywalls, products – El Faro, for example, makes T-shirts. It is very important to always be trying to vary the financing model. But that’s it: eternal sustainability does not exist.”

The Future of Pública

In October, the Brazilian electorate will go to the polls to vote for a new president, governors and federal and state congress members in an ultra-polarized political environment – fertile ground for the dissemination of so-called “fake news.” Pública’s greatest asset for this period is the expansion of its fact-checking project Truco. The idea is to check candidates’ speeches daily in at least eight Brazilian states.

For this, Pública’s staff in São Paulo will train independent journalists spread throughout the country on the agency’s fact-checking methodology. The operation was already tested during the 2016 municipal elections in five capitals and will be expanded in 2018, strengthening Pública’s performance at a newsworthy time in a far faster way than traditional investigative journalism.

“I consider fact-checking to be a genre of investigative journalism,” Viana said. “It’s like a short, concise little model. It’s super interesting because they found a way to quickly do investigative journalism without it having to be a long story.”

The agency has also strengthened its production of video reports, which, according to Amaral, have a significant international reach. Some of the agency’s mini-documentaries have already been shown at film festivals and on the Brazilian channel Futura. But one of the objectives is to consolidate Pública’s presence on TV – something considered with the genesis of the special Amazônia Resiste, which features video reports, Amaral said.

“Joining technology and shoe-leather reporting is very typical of Pública,” Amaral commented. “When I went to the ISOJ (International Symposium on Online Journalism) in Austin, one of the conclusions of the congress was that good old investigative journalism is still the most important thing we have. We only have new tools to use.”

This story, which first appeared on the Knight Center Journalism in the Americas blog, is part of its Innovators in Journalism series, made possible by the Open Society Foundations (OSF). The series covers digital news media trends and best practices in Latin America and the Caribbean. OSF is a funder of GIJN.

Carolina de Assis is a Brazilian journalist. She holds a master’s degree in Women’s and Gender Studies from the GEMMA Programme – Università di Bologna (Italy) / Universiteit Utrecht (The Netherlands) and has worked as a news editor at Opera Mundi, a Brazilian news website.

Carolina de Assis is a Brazilian journalist. She holds a master’s degree in Women’s and Gender Studies from the GEMMA Programme – Università di Bologna (Italy) / Universiteit Utrecht (The Netherlands) and has worked as a news editor at Opera Mundi, a Brazilian news website.